Handpaint Your Own Yarn

Never dyed before? Here's

a guide to creating your own handpainted yarn.

From the left, hot pour, cold pour, and dip-dye

methods.

Ever had a desire to

create your own variegated yarns? Mix exactly

the colors you want on exactly the yarn you

want, to create something uniquely your own?

You’ve come to the right place.

For years I thought it would be too messy,

too complicated, and too expensive to dye my

own yarns. I was wrong. What it is, is fun.

With a potential for mess, sure, but it’s

FUN! And did I mention, fairly inexpensive?

Below are three common

ways to make handpaint yarns; I’ve arranged them in order of

difficulty, though none of them are truly hard

to do. The only real dangers are making a mess,

felting the yarn (though that’s easily

avoided by using superwash), or making something

ugly. The yarn police won’t come after

you for making ugly yarn. Come on, give it

a try.

COMMON CONSIDERATIONS:

Regardless of what method you use, there are

some factors to consider.

Safety:

Using acid dyes developed specifically for

dyeing protein fibers can be dangerous. It’s

suggested you wear a filtration mask when

handling the powder to avoid breathing it,

avoid coming into contact with it, avoid

breathing the fumes when you heat it to set

the color, and you can’t use any utensils

you use when dyeing for anything else. The

dyes have to be special-ordered or purchased

from hard-to-find retailers, and used in

conjunction with other chemical additives

that are just as difficult to find and often

just as dangerous. Then there are the disposal

issues for whatever you don’t use.

Organic, plant-based dyes aren’t much

better; the plants themselves are often poisonous (pokeberry, anyone?),

and the mordants can be insanely toxic –arsenic and copper sulfide

are just a few of the more deadly chemicals you’ll play around

with. I have a toddler, and the idea of having anything like that near

her makes my blood run cold.

The answer? Food coloring. I know, I know.

It all seems so grade-school to dye your wool with food coloring, and

the colors are so candy-bright. But the safety considerations are just

about nil (you could DRINK the stuff if you didn’t mind multi-colored

innards) and you can use all your regular kitchen utensils to work with

it. Candy colors can be avoided with overdyes, clever mixing, or careful

regulation. Though I, for one, like bright colors. It’s one of

the reasons I started doing this; most handpaint yarns are done in bleeding

pastels or darks, which while nice, just aren’t my cup of tea.

To dye with food coloring

(well, to dye with anything, really, but

we’re sticking

to food coloring), you need five things:

-Yarn. FOOD COLORING AS A DYE ONLY WORKS ON

PROTEIN/ANIMAL FIBERS. For beginners, superwash

wool is your best bet. It’s unfeltable,

easy to find, and affordable. If you’re

looking for bright colors, get white (I have

produced neon colors with neon food coloring

on bright white yarn in the past). Cream is

good for normal colors and pastels, light gray

for pastels and neutrals. Cream is probably

best for starting off with. In these tutorials,

all yarn is Patons “Classic Wool” worsted

weight, in color ‘winter white’.

It’s not superwash, but it IS what I

had on hand when I decided to dye some yarn

for this article. Which is another great thing

about dyeing your own yarn – you can

transform what’s in your stash into something

new. You can even, gasp, dye light yarns in

solid colors with this method, but where’s

the fun in that?

-Colorant. In our case, food coloring. For

most of my dyeing I use Wilton’s paste

food coloring, but occasionally I will use

McCormick’s liquid food coloring (the

stuff with four colors in a box, with little

dripper bottles). For each dye job, I specify

which I used, but either one works. Both are

available on line. Wilton’s can also

be found at most craft stores that cater to

cake decorators and candy makers, and McCormick’s

is available in most grocery stores. Regardless

of what you use, you want to dissolve it in

boiling water before use, paste and dry or

granulated colors in particular. If you can’t

find the brand names mentioned here, get something

else. They’re all made with the same

dyes and chemicals, they just have different

names. To preview the color, dab a bit of your

dissolved color into a white paper towel.

Food colorings dissolved in water and

ready to be used as dyes.

-An

acid. In our case,

vinegar. Safe, easily disposed of, and available

at the grocery store in one gallon jugs if

you want to buy in bulk. Acid opens up the

fibers, chemically speaking, and makes the

color stick. The more acid, the brighter

the color, and the faster the dye ‘hits’,

or takes up into the yarn. There also seems

to be some funky reaction going on between

the vinegar and food coloring; if you use more

than ¾ cup/175ml vinegar at a time,

it can make blues and purples take up red and

blue at different speeds. The best way to avoid

that is to soak the yarn in vinegar-water the

night before and then add a small amount of

vinegar to the dye pot, instead of just using

a whopping dose with the dye. For each dye

method, I specify how much vinegar went where.

You are welcome to experiment, and do it your

own way. There’s no wrong way to do this.

-Water. Seems like a no-brainer, but depending

on the chemicals and minerals dissolved in

your water, your dyes won’t necessarily

look the same as mine do. If you know there’s

a lot of chlorine or iron in your water, you

may want to consider using filtered, or picking

up a couple gallons of spring water at the

grocery store. I used tap water, but the water

in my city is fairly clean.

-Heat. You can get it from a crock-pot, a boiling

pot of water on the stove, steam, the oven,

or even your

dishwasher,

but you’ve got to get the yarn as close

as possible to boiling without going over,

for about fifteen minutes, to set the dye and

make it colorfast. I used a crock-pot for two

of these dye methods, but with careful heat

management you could do the same thing on the

stove with a large pot.

Notice you can buy

all your supplies but the yarn at the grocery

store? Yep. Safety is our middle name. (Well.

Really our middle name is ‘cheap’,

but we like safety too. Cheap and safe at

the same time? Bliss.)

SKEINING YARN:

I never thought to

include directions on this, until someone

asked me how to do it. Then I realized it

really isn’t something everybody

knows. So here you go.

If the yarn is in a

ball, wind it off onto a niddy-noddy (if

you have one), or a handy piece of furniture

that’s nice and sturdy.

I regularly use my kitchen table to wind off

longish skeins. The advantage to winding it

on your table is, it’s automatically

the right size to spread out on the same table

later, if you’re doing cold-pour dyeing.

If the yarn is already in a skein, you can

leave it as-is, or wind it off onto a longer

or shorter skein, as desired. If you leave

it as-is, make sure it has enough wrap-ties

to keep it from tangling in the dye pot and

wash.

The length of the skein

determines the length of the pattern repeat.

If you have something specific in mind in

terms of self-striping yarns, you need to

knit up an example, unravel it and figure

out how much of each length you need, and

figure out how to arrange your living room

furniture to wind it into the proper length

skein (around the recliner, over the coffee

table, around the couch…). Me, I just

wind it off as the fit takes me and see how

it knits up later. Longer pattern repeats I

do on my kitchen table, shorter pattern repeats

I do on my niddy-noddy. If I ever decide to

try a really long pattern repeat, I’ll

probably use the living room furniture.

Tie the beginning of

the yarn to the end, and trim as needed.

You don’t want long

ends hanging out. By tying the two ends together,

you ensure that the yarn doesn’t tie

itself into knots, and when you find one end

later, you’ll have both of them.

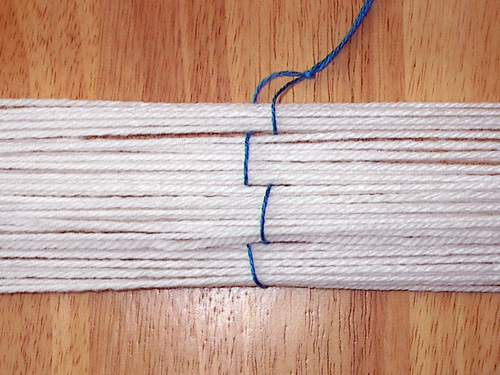

Get some waste yarn

(nice smooth cotton in a light color is ideal)

and weave it through the yarn; up and over

a few times, wrap it around, and come back

the other direction, like in the photo. Knot

the ends together. (I used the blue thread

in the photo so you could see what I was

doing. It did, indeed, bleed onto the yarn

later and turn it light blue. Stupid, stupid,

stupid.) Put one of these wraps every foot

and a half/half meter or so. They keep the

yarn from tangling. Don’t

make them so tight you accidentally tie-dye

your yarn.

Ready to try something? Here we go.

HOT POUR DYE METHOD:

This is the easiest

and least-messy of the three dye methods;

essentially you put your yarn in a crock

pot and pour dye over it. There are some

finicky details, but that’s

really all there is to it. Keep in mind that

the more dye you use, the more they mix together

when poured into the pot. Ditto, the more colors

you use, the more they mix. So for this method

it’s best to use related colors (like

blue/purple, or in this case, yellow/orange/pink)

or colors that mix into something pleasant

(blue/yellow/green). Avoid complimentary colors

(blue/orange, red/green, yellow/purple) because

they look like mud when they mix. Unless you

want mud.

I skeined up the yarn

on my niddy-noddy and soaked it overnight

with ¾ cup/175ml

vinegar mixed in, because I wanted the dye

to stick to the yarn quickly when it was poured

into the pot. (If you want yarn that is murkier

with the colors more blended, don’t use

any vinegar in the overnight soak.) In the

morning I drained off the soak water (and with

it, any vinegar left) and put it in the crock

pot with enough water to cover and ½ cup/125ml

vinegar. The amount of water to use in this

case is tricky; the more water you use, the

more the dye will spread when it is poured

in later. You need enough water to cover the

yarn, but after that, the amount is up to you.

I put the crock-pot on high (with no dye yet)

until I could see steam rising off the water;

that took about two hours for my crock-pot.

If you’ve got any meat or candy thermometers

around, you can pop one of those into the crock-pot

to monitor your progress (remember, all this

stuff is food safe, so you aren’t destroying

the thermometer OR the crock-pot).

While my yarn was heating,

I mixed up some dyes. I put three drops of

McCormick yellow in 1/3 cup/75ml water, and

dissolved 1/16 teaspoon/.2ml of Wilton’s paste food coloring, colors

rose and creamy peach, each in their own ½ cup/125ml

boiling water. There were three colors, total;

yellow, rose, and peach. I used liquid measuring

pitchers, one for each color, to make them

easy to pour later. (Paste food coloring HAS

to be dissolved in boiling water, with a lot

of stirring.) If you wanted to mix colors,

this would be the time, when the colorants

are dissolved in water. Add a little yellow

to make a green pop, put some blue in the rose

to make magenta, that kind of thing.

Once the yarn was hot,

I poured in the dye; peach on one side, pink

on the other, then blops of yellow in any

empty spaces. I clapped on the lid and left

it alone for an hour. When I came back, the

dye pot had ‘exhausted’ (meaning

the water was clear, and all the dye had stuck

to the wool), so I turned off the crock-pot

and let it cool for a couple hours, lid off.

When the yarn was back to room temperature,

I gave it a careful wash until the water ran

clear, ran it through the spin cycle of my

washing machine to get out any excess water,

and then hung it up to dry.

You can see from the

photo there were a good many places where

dye didn’t reach the

yarn. You can fix that by pouring in more dye,

though that will lead to more color mixing.

Or, you can wait until the dye pot exhausts,

stir the yarn around, and pour in more color,

leaving it to heat-set again before cooling

and washing. If I’d been using superwash

wool, I’d have done the stir-and-dye-more

method, but I didn’t want to felt the

yarn, so out it came with no stirring.

COLD POUR METHOD:

This one’s a lot more labor-intensive,

but you can pinpoint exactly where you want

your colors and run much less risk of mixing

them together. As you can see from the example,

I put compliments next to each other (blue/orange)

and pulled it off with minimal mixing between

them. You’ve got a much larger potential

for mess on this one, too. MUCH larger. For

small spills I suggest using bleach wipes to

clean up. For large spills, well, I’ve

been lucky so far, but mop them up and then

get the jug of bleach and a rag and have at

it.

You’ll need good-quality plastic wrap,

an oven, a baking dish of some kind, aluminum

foil, and I suggest rubber gloves. You don’t

NEED the rubber gloves, but you run the risk

of turning your hands and fingernails wonky

colors without them. There’s no real

danger in handling the colors, though, just

destruction of your manicure. Up to you.

Skein up your yarn

(I wrapped mine on the kitchen table) and

soak it with ¾ cup/175ml

vinegar overnight. Again, you want the dye

to stick to the yarn pretty quickly, so vinegar

in the soak water.

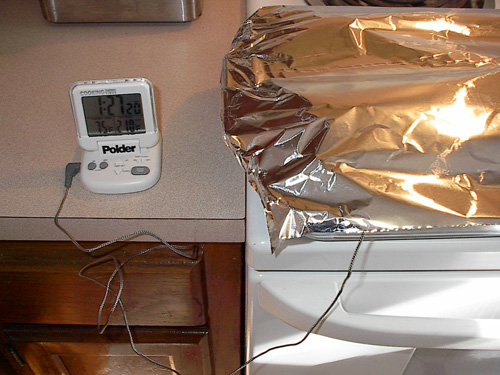

In the morning, preheat

your oven to 250F/120C and mix up your dyes.

I used ¼ teaspoon/1ml

creamy peach in ½ cup/125ml water, and ½ teaspoon/2ml

each teal and sky blue in 1 cup/225ml water,

to make three dyes, peach, teal, and sky blue.

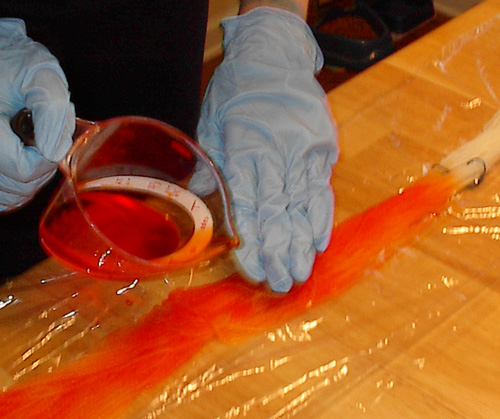

Spread plastic wrap

out on your work table in a circle. Drain

your yarn (you want it dry enough that it’ll take up your dyes and

not drip, but not bone dry) and place it on

the plastic wrap, adjusting carefully so everything’s

positioned right. Then pour your dye onto your

yarn where you want it, squishing it into the

yarn as you go so you have even coverage. I

suggest starting a small distance away from

where colors meet and squishing the dye up

to where the two colors join, instead of pouring

directly onto a color join. That helps keep

the colors distinct. (If you want them to blend,

why, then, squish them together. You get the

idea.) When you’ve got dye squished into

the yarn where you want it, wrap it all up

in the plastic wrap and carefully transfer

it to a baking dish. Keep any light colors

at the top of the yarn pile so that the other

dyes don’t run down into it and muddy

it up.

Cover the whole thing

with foil to hold the steam in, and pop your

baking dish into the oven for a couple hours.

If you’ve got

a meat thermometer laying around your kitchen,

tuck it in between the layers of yarn (since

it’s all food-grade dye, you can use

your meat thermometer on your pot roast again,

even if it turns colors, which it shouldn’t).

You want the yarn to stay just below the boiling

point for at least fifteen minutes. The thermometer

makes it easy to tell what’s going on

without lifting the foil and letting out all

the heat you’re trying to accumulate.

Once the yarn’s been heated, take it

out, remove the foil, and let it cool; that

will take several hours. When it’s room

temperature, take it to the sink, cut it out

of the plastic wrap (be careful not to cut

the yarn when removing the plastic wrap – one

lesson learned the hard way), and give it a

wash. Be careful to keep the light colors away

from the dark until any leaking dye has been

removed from the plastic wrap, and everything’s

been given a quick rinse; again, that’s

to avoid muddying up the lighter colors. I

have heard tell of permanently melting plastic

wrap to yarn with this method; that’s

why I suggest getting good-quality plastic

wrap and not cheaping out on the generic stuff,

just this once.

When the yarn’s

been washed until the water runs clear, give

it a spin through the washer (or roll it

up in a towel and stand on it) to remove

the excess water, then hang it up to dry.

DIP-DYE METHOD:

The main reason I used

this method was to show the wide potential

for color variation with food color dyes.

All colors on the skein were done with unmixed

royal blue color from Wilton’s. Of all three methods shown

in this article, I think this one has the most

potential for disaster. The technique isn’t

difficult – none of them are – but

this one involves handling the yarn a lot,

exposing it to a lot of dye, a lot of heat,

and a lot of vinegar. Plus there’s a

lot of mad scientist mixing and pouring and

stirring going on, so if you’re ever

going to pour dark blue dye over your kitchen

floor, it’s most likely going to happen

during this method.

I created a long skein on my kitchen table

again, about two yards/two meters long when

held up from one point and allowed to hang,

maybe four yards/four meters in total circumference.

I put in a lot of loop ties to prevent tangling,

because I knew this yarn would be handled a

lot. Then I soaked it overnight in plain water

with no vinegar. With a dip-dye, you want the

dye to soak in slowly, over a period of time,

not stick the instant you dunk the yarn. So

no vinegar this time around.

The next morning I

filled the crock-pot with 8 cups/2 liters

of water and ¾ cup/175ml

vinegar. In one cup/225ml boiling water, I

dissolved an entire teaspoon/5ml of royal blue

coloring. (That’s a lot of dye. Wait.

It gets crazier.) I waited until there was

steam rising from the crock-pot, and stirred

in the dye. It was so dark I couldn’t

see the bottom of the pot.

I drained the water off the skein, found an

end (with it folded in half), and carefully

lowered all but a handful of yarn into the

brew, swished it around, and immediately pulled

four inches/ten cm back out of the pot. Leaving

that to hang down the side of the crock-pot

into a bowl, I put the lid back on and let

the yarn stew for ten minutes. Then I pulled

another four inches of yarn out of the crock

pot, put the lid back on, and let it go for

twenty minutes. As the yarn that had been pulled

out cooled, I would squeeze the water and dye

out into the bowl it was hanging over, and

then move it on to a plate. Note that the very

end of the yarn skein never met the dye; the

very light blue was created by dye wicking

up the fibers from the parts that were dipped.

I continued this for

most of the afternoon; each time I pulled

out four inches/ten cm of yarn, I would lengthen

the time the rest was left in. After the

twenty minute pause, I left the next round

in for half an hour and pulled another four

inches; then forty-five minutes and pulled

another four inches. Whenever the dye pot

started to exhaust (I could see the bottom

of the crock-pot and the water was noticeably

lighter blue), I would top it off with another ½ teaspoon/2ml

of royal blue dissolved in ¾ cup/175ml

boiling water and give it a careful stir. By

the time I pulled the final bit (the very dark,

navy blue) out of the pot, it had been in there

approximately four hours, and I had topped

off the pot with dye three times. (It’s

a miracle I didn’t felt it into one solid

mass; I strongly suggest using superwash if

you ever try this. And lock the cat out of

the kitchen or wherever you’re mixing

the dye.)

Most of the skein was

already cool when I pulled the last bit from

the crock-pot, so it didn’t take too long to reach room

temperature. As always, I gave it a wash. Of

the three dye methods I’ve discussed,

this one bled the most during the wash and

required four or five rinses; it’s heat

that sets the color, and the first sections

dyed – the pastels – didn’t

spend much time at all in the heat, so the

dye washes right back out again. Make sure

to get it all.

Then I hung it up to

dry – away from

the baby and the cat, that’s always tricky – and

then put it in a more workable skein size on

my niddy-noddy the next day. Amazingly, the

yarn was not tangled and wound up easily. I

can only attribute it to luck and lots of woven

ties. Then I hung it up to

dry – away from

the baby and the cat, that’s always tricky – and

then put it in a more workable skein size on

my niddy-noddy the next day. Amazingly, the

yarn was not tangled and wound up easily. I

can only attribute it to luck and lots of woven

ties.

There you have it.

Three totally different looks, all created

with some food coloring and stuff most people

have laying around their kitchens. It really

is this easy; the hardest part for me was

not spilling dye all over the place and wrangling

my toddler during the entire afternoon it

took to do the dip-dye. (The other dye methods

I did while she was napping.) For cleanup,

I washed out my crock-pot with bleach (it

did turn a nice shade of blue-lavender during

the dip-dye), wash it out again with soap

and water, and it was bright white and good

as new. If you have a choice between glass

or metal utensils, glass stains less and cleans

up more easily, but even stained, the utensils

are still safe to cook with – I made

soup the other night with a bright pink wooden

spoon.

Dig through your stash,

find something you’ll

never knit up as-is, and experiment! It brings

out all kinds of happy kindergarten finger-painting

memories.

NOTES:

Food coloring available at www.wilton.com and

your local grocery store. www.mccormick.com contains

information about liquid food colorants.

There were some books I found helpful when

learning to dye. In order of usefulness to

me, they are:

“The Twisted Sisters Sock Workbook” by Lynne Vogel, which

contains a great deal of information about dyeing and spinning as well

as socks.

“Dyeing to Knit” by Elaine Eskesen.

“Yarns to Dye for” by Kathleen Taylor.

“Wild Color” by Jenny Dean with Karen Diadick Casselman.

This covers plant dyes and their mordants. Very educational and kind

of scary if you know hazardous materials. (Mix up copper sulfide in the

comfort of your own home! Eeek.)

For food coloring dye jobs, I found The

Dye Pot very educational.

There is a fine imperial/metric

conversion chart available here. By

using it, you can see the amounts I give aren’t

exact. Exactness doesn’t really matter

unless you’re trying to duplicate something

you've already done; otherwise, a few milliliters

either way won’t make much difference.

For details of mixing

colors and explanations on why complimentary

colors look like mud when mixed (among other

things), “Color” by

Betty Edwards is helpful, though it’s

a book mainly slanted toward painters and mixing

paint.

All photos by the author or The Husbeast.

|