The

second dimension: adjusting knitting

patterns for width

In the last

article,

we looked at length adjustments. Altering

the length of a garment that's knit vertically

-- either from hem to shoulder, or top-down

from shoulder to hem -- is relatively

easy. Really, there are only a few ways

that you can make adjusting the length

of a garment hard:

- If you are lengthening or shortening

an item with horizontal stripes or

horizontal patterning, you should make

sure that you are happy with where

the patterning will begin or end.

- If your length alteration affects

the armscye for a set-in or modified

drop-shoulder sleeve, then you will

need to recalculate the instructions

for the sleeve cap. However, upper

front and back length alterations to

a drop shoulder sweater do not necessary

require that the sleeve be reshaped.

- If your length alteration also results

in making the sleeve narrower,

make sure the sleeve does not wind

up being too tight.

Even these tricky bits

about length adjustments are easily handled

with a little bit of forethought. But

changing the width of a garment

is a different matter. Although it depends

on the amount of alteration required,

it's generally more challenging to adjust

somebody else's knitting pattern in this

dimension. Why?

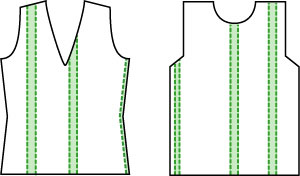

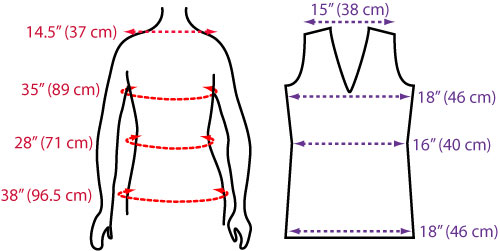

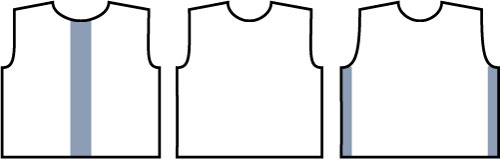

|

| If

you needed to adjust the width of

these tops, where can you add or

remove that extra width without distorting

the fit of the rest of the garment?

At the side edges, shoulders, neckline,

or some combination of the three? |

- The pattern may lack sufficient finished

measurement information (or a schematic)

for computing width alterations.

- The pattern

may lack information about the appropriate

amount of wearing or design ease.

- Just because you need to add or subtract

width in one part of the garment doesn't

mean that you need to make that same

adjustment everywhere else.

- The adjustment you need to make might

require adjustments in more than one

place.

- You may have chosen the wrong pattern

size as your starting point.

- The alteration

you wish to make is not merely a fitting

adjustment; it's a style change.

Some

of these factors, such as a lack of

pattern measurements or ease information,

simply aren't your fault, but you can

correct them. The last two factors

are within your control, and can make

the difference between a successful

alteration and throwing your calculator

at the wall.

Choosing the

best pattern size as a starting point

The need to pick the

right starting size is probably a no-brainer.

You'll minimize the amount of alteration

you need to do, of course. But there's

also a little bit of strategy behind

choosing the size that will make fitting

adjustments easiest:

- For a set-in

sleeve style, pick the size with

the cross-shoulder measurement that

fits you best for the design style. That

way, you won't have have to fuss

with widening or narrowing the shoulders.

This also means that even

if there's a finished bust measurement

that looks perfect for you, don't

use it if the shoulders won't fit!

Generally, it's easier to tweak the

size of a garment around the torso

than it is to adjust the upper body

width.

- For a raglan

sleeve style, pick the size with

the full bust measurement that fits

you best for the design style,

provided the armhole depth is sufficiently

deep to be comfortable. The raglan

style doesn't have a defined shoulder

line, so fitting the shoulder is

usually less crucial; the biggest

fitting problem is usually the armhole

depth. Usually, the armhole depth

will be just fine, but sometimes

(especially in body-conscious styles),

it might be on the shallow side,

and potentially tight and uncomfortable.

However, raglan yoke shaping lends

itself to easy armhole depth adjustments,

so it's generally safe to pick the

size that matches your target bust

measurement, and alter the armhole

depth if necessary.

Your

cross-shoulder measurement

is the distance between your

shoulder points. But where

is your shoulder point, anyway?

It's hard to find the bony

mass that so many knitting

references mention.

The

shoulder point is not the

exterior of your upper arm,

and it's not the protruding

bit of your clavicle that

sticks up; it's somewhere

in between, and a fair estimate

is halfway between those

two reference points. The

cross-shoulder measurement

is the distance between these

two shoulder points, measured

from the front. As you age

and gain (or lose) weight,

this measurement will stay

fairly constant, and in reality

the variation in this measurement

across women's sizes is less

than current knitting standards

might have you believe. The

real-life variations in fit

at the shoulder are due more

to the amount of flesh on

people's frames than on

the bones themselves. |

- For a drop-shoulder

style, pick the size with the full

bust measurement that fits you best

for the design style. Most

drop-shoulder styles are designed

with generous ease and significant

differences between adjacent sizes,

so it's not too hard to identify

the right pattern size.

- For a modified

drop-shoulder style where the sleeve-body

seam is dropped and falls across

the upper arm, pick the size with

the full bust measurement that fits

you best for the design style. If

the sleeve-body seam does fall

at the shoulder, then treat it like

the set-in sleeve style, and choose

the size that puts the sleeve-body

seam in the right place.

In other words, if

the garment style relies on a sleeve-body

seam falling in just the right location,

choose the size that makes this work

on your body so that you can avoid having

to make adjustments to the upper body.

Otherwise, if you have to make alterations

in that area, then not only do you have

to worry about armscye depth and decreases,

but you might have to rejig the shoulder

slope and neck opening.

Previously, we've discussed how

to pick the right starting size.

If you've forgotten about that in the

meantime, it might be a good idea to

go back and read it, because we're

going to pick up right where that left

off. From here on in, we're going to

assume that you've already picked out

the best pattern size as a starting

point. Hopefully, the pattern may include

some information on ease, which is

important in helping you pick the right

size to begin with. Without it, you're

reliant on the subtle clues that might

have been provided in the finished

measurements, the accompanying photographs,

and what pattern writer's idea of a

size small/medium/large/etc. might

be. Is the garment supposed to be roomy?

If the schematic suggests a loose fit,

but it looks tight on the model, read

through the pattern to see if there's

an explanation: perhaps part of the

garment is gathered, tied, or laced

up.

Understanding

the difference between altering to fit and

altering the style

You

need to recognize what kind of "adjustment" you're

making to the pattern: do you really just

want to tweak it

to fit your body shape,

or is your intention to change the

style? These are two different types

of alteration.

If you just want to

add a couple of inches to the finished

bust measurement because your target

finished size is between two pattern

sizes, or if you just need to size the

pattern up or down because the pattern

sizes aren't quite large or small enough,

that's probably just a size alteration.

But

if you find yourself saying "I'd love this sweater if only

it had raglan sleeves (or set-in sleeves,

drop shoulders, etc.) or if it was tighter

(or looser) fitting" or "I need to alter

the pattern because this type of sweater

makes me look like I'm wearing a tent",

then chances are you're wishing you could

change the style lines of the garment.

While it may certainly be possible to

do this, that's not a size alteration

-- that's a redesign. For example, consider

the traditionally-styled Fair Isle or

Aran sweater: the fabric looks beautiful,

and may blend color and texture like

a painting by an old master... but just

like an old master's painting, the garment

is shaped like a big rectangular canvas.

Cutting it down to a figure-conscious

shape may be possible, but takes a lot

more planning and computation than a

mere fitting alteration to preserve the

colour or texture pattern that drew your

fancy to the design in the first place.

(There are some measures you can take

to reduce the boxiness of a big, sack-like

Fair Isle or Aran pullover, while preserving

its general structure... but that's a

later column.)

Certainly both types

of alteration will involve some kind

of width adjustement, but changing the

garment style is a significantly

bigger undertaking; in some cases, it's

easier to simply start from scratch rather

than alter an existing pattern. In the

meantime, we'll focus on the easier tasks:

adjusting a pattern when you're between

two sizes, or increasing or decreasing

a size or two beyond the pattern's size

range.

A broader (or

narrower) view: adjusting the hip measurement

Having picked out the

correct starting size in the pattern,

the next step is to figure out what kind

of alteration is necessary. For this,

we'll work through a series of exercises.

Let's assume that we're

trying to fit a narrow-shouldered woman

with a cross-shoulder measurement of

14.5 inches [37 cm], a full bust measurement

of 35 inches [89 cm] (with a cup size

that does not require the addition of

short rows), a 28 inch [71 cm] waist,

and 38 inch [96.5 cm] hips. Let's also

assume that the pattern to be fit is

a slim-fitting style with waist shaping

and about an inch of ease in the body,

and that we managed to find a pattern

size that fit the upper body (from the

waist to the shoulders) perfectly:

|

| Our

fit model for this exercise, and

the first pattern to be adjusted.

While the patterns we adjust may

be close-fitting, We will assume

that the pattern will have the typical

proportions of a hand knitting pattern:

the widths of the front and back

pieces at all points are equal (e.g.

full bust measurement, shoulders,

hips). Recall that pattern schematics

show flat dimensions: a hip measurement

across the front of 18 inches corresponds

to a 36 inch circumference. |

As you can see, our

pattern here has a finished bust measurement

of 36 inches [91.5 cm] (which is twice

width of the front, shown in the pattern

schematic at right), but the hips are

the same dimension: a touch too narrow

for 38 inch [96.5 cm] hips. While it's

still wearable, it will have

to stretch to fit the wearer's hips.

You'll

often find that in hand knitting

patterns with waist shaping,

the circumference of the garment

at the hem is often very close,

or equal, to the circumference

at the bust. The shape of the

garment body thus resembles an

hourglass, like the schematic

of our pattern above.

On

real bodies, hips and full

bust measurements are not usually

equal -- hence the fitting

problem we have here. Usually,

the hourglass shape of the

pattern does not pose a problem,

because pullovers with waist

shaping typically end above

the fullest part of the hip.

However, if the garment is hip

length or longer, then this

hourglass shape may not fit,

and you'll need to make an

adjustment like the one we're

about to make. |

If your pattern lacks

measurements or a schematic, you'll want

to supply your own in advance of calculating

your alterations. In fact, even if your

pattern does have schematics, you might

want to draw your own, anyway, in a larger

size with more room for writing in numbers

and dimensions. In fact, make two: one

set labelled with the original dimensions

of the chosen size of your pattern, and

one with your target dimensions. Your

schematics don't have to be to scale,

they just need to be big enough to scribble

on.

On your schematic with

the original dimensions, run through

the pattern numbers at the key points

to calculate the original measurements:

the beginning and/or end of each shaping

zone, such as the wrist, bicep, hem,

hip, waist, full bust, shoulder, and

the neckline width, too. Also pencil

in any finishing bands, like neckbands,

and make a note of their depth; look

at all those numbers, and compare them

to the measurements you need to fit the

wearer (taking ease into account). Make

a note of the dimensions and the stitch

counts at each point, according to the

original pattern; if you're going to

be making adjustments, you might as well

write down your starting information

now. Keep in mind whether there are selvedge

stitches, which are incorporated into

seams, or not; your finished measurements

should not include the selvedge stitches,

but you should keep track of those stitches

as well.

On your other schematic,

write down your target dimensions. Your

target finished dimensions should take

the design ease into account, and figuring

them out should be a simple exercise

in arithmetic. In this example, the finished

hip circumference will be too tight,

so in keeping with the overall ease of

the garment we've decided that we need

to add 3 inches [7.5 cm] at the hips

(our model's 38 inch [96.5 cm] hips plus

1 inch [2.5 cm] ease equals a total of

39 inches [99 cm], 3 inches [7.5 cm]

more than the original pattern).

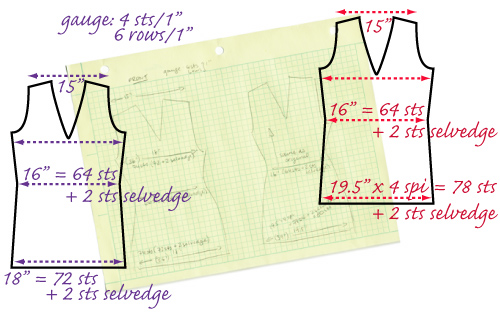

|

| When

you sketch your schematics, don't

forget to make a note of selvedge

stitches. While they don't count

towards the finished dimensions,

you certainly need to remember them

when you're knitting. For simplicity,

not all measurements and stitch counts

are shown in this diagram. |

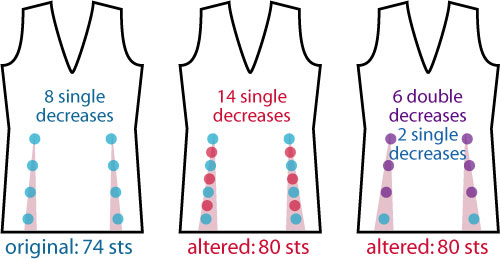

Next, having figured

out the target dimensions for the garment,

it's time to figure out what to do to

the pattern itself. According to our

gauge in this case, 4 stitches per inch

[2.5 cm], we're adding 12 stitches to

the hip circumference to provide that

additional 3 inches [7.5 cm] required.

This translates to an additional 6 stitches

for each of the front and back: each

of the front and back now has 80 stitches

(78 stitches plus 2 selvedge stitches),

whereas the original pattern only had

74 (72 stitches plus 2 selvedge stitches).

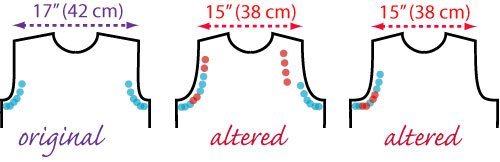

|

| Having

added in the extra stitches, there

are a number of ways to decrease

them to reach the original stitch

count at the waist. You could convert

some rows previously worked even

to decrease rows (center; red dots

represent new decrease rows), or

you could convert some decrease rows

to double-decrease rows (right; purple

dots represent double decreases).

The light red shading shows how the

added width is gradually removed

towards the waist. |

Because this alteration

only requires a change to the region

below the waist, we now need to figure

out how to subtract these extra stitches

by the time we reach the waist. Six stitches

will need to be decreased on each of

the front and the back; how they're

decreased will be determined by how other

decreases are handled in the same region.

Depending on your pattern instructions,

you may simply choose to insert extra

decrease rows between the decrease rows

already provided, or if the decreases

are all single decreases (two stitches

reduced to one), you might decide to

substitute double decreases for three

pairs of decreases on the front and back,

as shown in the figure above.

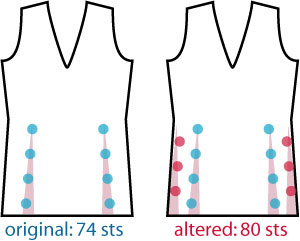

|

| If

the patterning of the fabric doesn't

allow for additional decreases to

be inserted into the existing (blue)pattern

of decreases, then add the extra

stitches at the edges of the piece,

and decrease them at the edge of

the piece as well. |

The above suggestion

works for plain fabrics, but it's not

always that easy, of course. Perhaps

the sweater starts out with ribbing,

or some other hem treatment that doesn't

lend itself to the increased stitch count.

Or perhaps the sweater is textured or

patterned in a way that will be thrown

off kilter by incorporating extra decreases

into the existing line of decrease stitches.

In that case, consider adding or subtracting

stitches at the sides, for example in

a background stitch (stockinette, reverse

stockinette, or a texture or colour pattern

with a small repeat).

Another example:

reducing the garment circumference

and cross-shoulder measurement

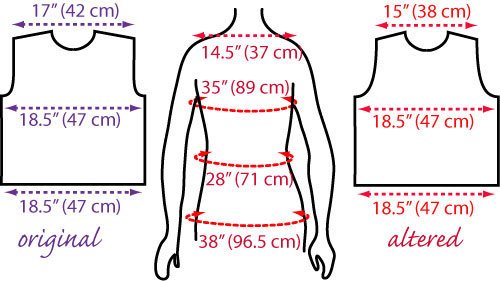

Again, with the fit

model we used above, let's assume that

now we want to fit a cropped, set-in

sleeve pattern that's meant to fit with

2 inches [5 cm] of ease at the bust.

The closest pattern size has the correct

bust measurement, but it's written for

a woman with broader shoulders: while

the sleeves are set in to the armscye

and are not meant to be dropped, the

schematic (and stitch count) tells us

that the distance across the shoulders

and neck is 17 inches [43 cm]. We happen

to know that for this style of sweater,

our wearer is happiest with a sweater

with a cross-shoulder measurement of

no more than 15 inches [38 cm].

Based on these numbers,

you can see that we need to reduce the

cross-shoulder width of the garment by

2 inches [5 cm] on each of the

front and the back, but without affecting

the dimensions of the body from the bust

area downwards. So, whatever changes

we're making, we need to keep above the

bust point.

|

| The

original schematic (left), and the

target dimensions (right). What our

fit model (center) needs here is

an adjustment that brings the cross-shoulder

measurement in to the proper width,

but depending on the original dimensions

of the pattern, there are three different

places where adjustments may be made. |

Depending on the overall

shape of the garment front and back,

an adjustment to the shoulder width might

need to be made in a number of places.

We need to identify where that extra

cross-shoulder width is coming from:

is it due to an extra-wide neckline or

extra-wide shoulders?

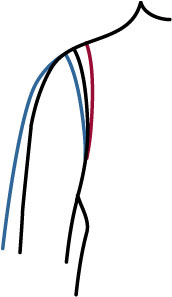

|

| An

extended shoulder (blue) extends

the edge of the armscye past the

natural shoulder point; a narrow

shoulder (right) results in a narrower

shoulder seam, ending closer to the

neck. |

As a rule of thumb

(which is as variable as all other rules

of thumb), in a set-in sleeve style where

the sleeve-body seam is intended to sit

at the shoulder point, the cross-shoulder

measurement will remain constant for

a particular wearer regardless of the

design ease. Naturally, there are exceptions;

if a garment is intended to be worn over

multiple layers, then the overall fit

of the garment will be looser and additional

shoulder room may be provided by extending

the shoulder line past the shoulder point.

If the garment is styled with narrow

shoulders, then the sleeve-body seam

may fall short of the shoulder point,

for example at the end of the clavicle

(like a tank top). But the rule of thumb

does allow you to assume that the

wider the neckline, the narrower the

shoulders will be, and the narrower the

neckline, the wider the shoulders will

be.

Typically, in a set-in

sleeve garment where the sleeve-body

seam falls at the shoulder point, the

width of the shoulder seam itself (the

seam that joins the front and back at

the shoulder), extending between the

shoulder point and the neckline, is between

4.5 and 5.75 inches [11.5 and 14.5 cm].

Some garments are intended to have wide

necklines as a design feature. Thus,

in a set-in sleeve garment with a wide

neckline, the shoulder seam should be less than

that typical range; if your schematic

tells you that the neckline is wide and the

shoulder seam is just as wide as a typical

shoulder seam, then either the neckline

must be narrowed, or the shoulders, or

both.

In order to determine

whether the neckline is too wide, you'll

need to compare the width of the neckline

from the schematic to where it would

fall on your body -- but don't forget

about the neckline finish! If you included

that in your schematic, then you won't

erroneously conclude that the neckline

requires narrowing when in fact the neckline,

once finished, is just the right width.

In this case, we'll

assume that the neckline width is just

fine, and that it is not in need of adjustment.

But if you do choose to reduce (increase)

the width of the neckline without making

any compensatory adjustments in the shoulders,

note that you will not only reduce (increase)

the cross-shoulder measurement; you'll

also wind up reducing (increasing) the

overall size of the garment below the

neckline.

|

| A garment

with an extra-wide neckline (left)

can be adjusted to bring its neckline

width to an appropriate size (center),

but this will result in a loss of

width throughout the garment (indicated

by the shaded rectangle at left).

If this is not the intention, a compensatory

adjustment must be made, for example

by extending the sides of the body

by an equal amount (shaded areas

at right). |

If the excess width

is to be removed from the shoulder fabric,

there are a few ways to do it -- which

method is best depends on the patterning

in the garment fabric, and whether any

changes are to be made to the sleeve

cap (or whether changes to the sleeve

cap are to be avoided altogether).

When faced with the

need to decrease a substantial amount

of width from each shoulder area -- here,

1 inch [2.5 cm] per side, in order to

bring the cross-shoulder width from 17

to 15 inches [42 to 38 cm] -- the easiest

solution might seem to be to

simply decrease the extra stitches as

quickly as possible, for example at the

underarm bind-off or in the series of

rapid decreases typically worked immediately

after a bind-off in a set-in sleeve armscye.

In the diagram below, this is the technique

used in the far right-hand example: the

original decreases are shown in blue,

and the added decreases are red. In the

far right-hand drawing, the added decreases

are inserted into the bind-off, and very

soon afterwards.

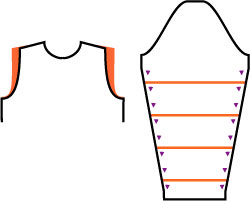

|

| Three

different ways to decrease the shoulder

width. At far right, the additional

decreases (red) are inserted into

the bind-off edge and in the rapid

decreases following the bind-off;

in the center, two ways of inserting

the additional decreases that minimize

the change to the armscye. |

The potential difficulty

with this technique is that it results

in a significant change to the shape

of the armscye. While a change to the

armscye is inevitable in this kind of

width adjustment, altering the decreases

in this manner results in the most extreme

change. If you make this alteration,

then you will have to consider what changes

will need to be made to the shape of

the sleeve cap: making the initial bind-off

deeper and squaring the shape of the

armscye will probably necessitate changing

the initial bind-offs of the corresponding

sleeve cap, and the perimeter of the

armscye may be lengthened as well.

Two alternatives are

shown in the center example. On the side

closest to the left, the additional decreases

(red) are interspersed with the original

decreases (blue), but the depth of the

initial bind-off is not altered; instead,

the decreases continue over more rows

than they had in the original pattern

(left-hand drawing). While the armscye

is also reshaped in this example, the

change from the original is not as severe

as in the far right example; you may

be able to get away with using the sleeve

cap as originally drafted in the pattern;

even though it will not be an exact fit,

it will probably be close enough.

|

| The

extra width that you removed (or

added) to the cross-shoulder measurement

may need to be added (or substracted)

from the sleeve. |

In the center drawing

on the right in the above diagram, the

added decreases (red) are not incorporated

into the armscye shaping at the edge

at all. Instead, they are worked in the

middle of the shoulder portion. As with

the other example shown in the center

drawing, the change to the armscye shape

is minimized. However, this set of additional

decreases may be more prominent, so unless

you wanted to make these decreases a

design feature, this method may only

be suitable if the stitch pattern will

help camouflage the decreases.

However this alteration

is made, though, you aren't finished

yet. Because you have changed the cross-shoulder

width, the wingspan of the garment (i.e.,

the measurement from wrist to wrist)

will have been changed, as well. As a

result, you may have to make a compensatory

change to the sleeve length as well.

This alteration would be made below the

sleeve cap, for example by inserting

extra rows between some of the increase

rows of the sleeve (right).

Next time,

more examples of width adjustments:

asymmetric adjustments to accommodate

a full bust, and more alterations that

affect the shape of the armscye and

the sleeves. |