|

| The whole Himalayan

Kids Sweater gang: Sonam Namgyal,

Rigzin Namgyal, Tsewang Namgyal,

Rigzin Gurmet (cultural note -

the repetition of second names

does not mean they are in the

same family. Everyone has two

names, neither of which is a family

name. Namgyal means "victorious.")

|

For the past

five years, I've been traveling annually

to Ladakh, a mountainous, high-altitude

region of North India. I go there to

spend time at a charity boarding school

amidst a rambunctious group of boys

with whom I am hopelessly smitten. How

did I get there, meet these children,

and start this long-distance love affair

with several dozen little kids? It's

a long story. What you really want to

hear about is the knitting.

I learned

to knit on one of my visits to the

boys. I'm a quilter and fiber enthusiast,

and finding myself surrounded by women

who know how to knit at lightening

speed and boys who need warm clothing,

it seemed only natural to take the

plunge and learn. Knitting never held

any appeal for me in the past -- none.

But with long, unscheduled days away

from my own projects, I finally reminded

myself that knitting is a fiber art,

after all, so it wouldn't hurt me

to know how to do it. (Go ahead, mock

my naivete, anyone who has witnessed

me of late, unable to pry my fingers

from the needles except, perhaps,

to sleep.)

And so it

happened that I learned knitting from

women who don't speak any English,

who don't follow written patterns,

and who have a very hard time slowing

down enough to demonstrate for a beginner.

|

| The

LYS in Leh, Ladakh. Ache Lhaskit,

shopkeeper. |

What is the

world of knitting like, up there in

Ladakh? Bear in mind that I frequent

an urban center of sorts, a town of

30,000 people in a region of merely

130,000. There are yarn shops. One

kind of yarn is offered there, produced

in the mills of Ludhiana, Punjab,

and trucked over the mountains via

Kashmir. Everyone knits on the same

size needles, equivalent to a US#1.

They come in straight and double-points

(known as "sock needles"), they don't

have circulars. Even large projects,

if round, are executed on DPN's --

I once saw a woman walking down the

street, knitting a full-size sweater

on 12 inch DPN's (and it wasn't even

plain stockinette!) They sell needles

in other sizes, but they're not popular.

I knit one vest last year on Indian

8's (roughly a US#5), and the boys

commented that the needles were "fat."

There's only

one kind of yarn, but it comes in so

many luscious, saturated colors that

it's hardly a limitation. Merely a simplification:

no one ever has to worry about gauge.

Entering a yarn shop in Ladakh is an

assault on the senses. Pure color sings

out from every shelf, veritable bushels

of it spilling along every inch of wall

space. Indian shops are generally cramped

and dim, but the yarns are plentiful

and bright enough to draw me in off

the street. I look around like I'm the

proverbial child in a candy shop, wondering

where to dive in. I shop by touch --

the yarn is largely acrylic, and the

softness variable, so I feel for the

softest ones and then go for the best

colors within that soft realm. Again,

this is not limiting: I'm easily able

to buy more than I can conceive of using

in the near future (isn't that the normal

amount?) I hoard colors until I land

on a stripe scheme and plunge into the

next project.

|

| My

very first vest is still in operation,

two & a half years later.

Modelled by owner Sonam Namgyal. |

In the beginning,

it was all about stripe schemes. My

first vest was fuchsia & blue,

fuchsia & blue, two rows of each,

and finished off with a purple neckline.

It was exactly like my favorite crayola

colors that all my childhood princesses

wore -- colors I could happily hang

with for the duration of the vest.

And the women taught me to knit the

vest flat, in two pieces, so it's

kind of like making socks: once you've

finished one, you have to start over

and do it again. I learned to do shoulders

(triple needle bind-off, unbeknownst

to me until months later when I heard

it explained at my Stateside LYS,)

and a ribbed v-neck with a double

decrease in the center. I could never

repeat the double decrease, and had

to be shown anew every time.

Doing one's

earliest projects on needles the size

of US#1 with a gauge of 6 stitches

per inch takes a lot of concentration.

My teacher Tsetan kept saying "tight

ma chos," and I understood what she meant, don't make

it tight, but how to not knit tight

eluded me. My stitches were so tight

I remember wedging the point of the

needle between yarn and needle and

twisting, worrying it in until the

body of it penetrated -- then the

problem was, how to wrap yarn around

and pull back through the unyielding,

forced hole I'd created. Many a false

attempt, until I'd hand it back to

my teacher who'd say "tight

ma chos" and

knit a few looser stitches, baffling

me. This method of learning requires

abject humility: despite the temptation

to question or explain, it's obvious

that no words are going to demonstrate

why Tsetan can knit loose and I can't.

|

|

Sonam Tsewang

models my first intarsia project

and a hat from the Villa Marin

knitters in California - seen

here with his friend Stanzin

Chospel. |

I kept at it,

wrestling each stitch through with determination,

and wrenching the whole fabric along

the needle. You know what comes next

- the fateful tug that yanks a good

half dozen stitches off the needle.

This only happened when I was surrounded

by boys, and I'd duck my head and clear

out an arm's length around me and say

"whoa, hang on,waitwaitwait" and frantically

poke back through the little diminishing

holes that threatened to vanish with

the least jog of my elbow.

Imagine knitting

on size 1 needles before you learned

to loosen up, sitting on the floor of

a carpeted room with forty-some boys,

watching a Hindi movie on TV. The light

is barely good enough to knit by, but

I'm knitting a few stitches a minute

anyway, interrupted when the boys point

out particularly cool heroes, fights,

or motorcycles. Knitting, knitting,

pulling the stitches along, looking

up, pulling stitches -- yikes! -- off

the needle, looking down and POOF --

no power. Pitch black. Silence. The

boys don't scream like American kids

do when things go black. Failed electricity

is so normal they hardly react, apart

from some sighs and "Light song..."

("Light is gone.") But there I sit,

dropped stitches hanging off my needle,

no light, and bodies beginning to mill

around me. Often, the light comes back

after a minute or two. If not, I gather

my yarn and get up, pinching the dropped

stitches firmly, and make my way into

the hall where there may be ambient

twilight at least. I don't think the

boys had ever seen a woman so tense

about knitting. No one in their culture

would begin to learn at my advanced

age (i.e., over 30).

|

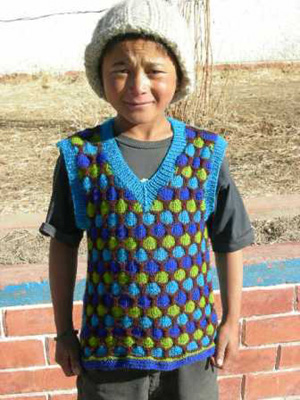

| Big Dotty hits

Ladakh! Shout out to Ann

& Kay - modelled by owner

Stanzin Chamba. |

Now that I'm

going back with some serious knitting

experience under my belt (witness:

the first year I made four vests;

the second year four vests and one

full sweater; this year I'm carrying

seven sweaters, three vests (one hooded),

and a vest and mini-poncho for me)

I plan to experiment with colorwork,

beyond stripes. I love stripes, but

all those colors beg for fair isle

designs. The only catch to this plan

is the environment: more than 80 boys

live there now, aged 3 to 14. The

best knitting under such circumstances

is that which can be dropped at a

moment's notice, to catch a ball or

help with homework or break up a fight.

If I need to pay attention, I may

have to wait until they're gone to

school. Okay, so I'll knit some stripes

for the social hours, and play with

colorwork during school time. These

days it's normal for me to have multiple

projects going.

The greatest thing about

knitting for 80 boys between the ages of 3-14

is it will always fit somebody! I

use these vests and sweaters as a training ground,

to see what I can do, and then it ultimately

wraps around the little body of someone I adore,

and I get to see my work running around the

most beautiful landscape in the world.

|