Reworking

Bacardi’s Color Chart

|

The original Bacardi

[photograph from No Sheep for You,

© and

courtesy Interweave Press] |

Color is a wonderful

and powerful force in the world of knitting.

I believe all knitters love color, and it

can play as big a part in their knitting

decisions as the fibre or the garment’s shape. A shawl or sock pattern

that got passed over when shown in one color

may suddenly become desirable when seen in

one of the knitter’s favorite colors.

This is one of the reasons we love to knit:

whatever we are making, we get to choose the

color.

A few years ago I decided

to knit myself a cardigan. I had a generous

stash of Super 10 Cotton, but no two skeins

were the same color. Wanting something simple

to knit I decided to make it striped, and

to break up the visual tedium of stripes

I mixed in dots and dashes. I chose from

among the warm tones that suit me best. Dark

gold, olive green, a pale, creamy yellow:

these are old favorites for me. A light,

sandy neutral helped to tone down the mix

and keep it from being too intense. A bright,

lime green, used sparingly, was a pleasing

accent. And finally a sage green — in

the context of the warmer tones it appeared

almost turquoise, and looked so pretty next

to the cream or the gold that it secretly

became my favorite child in this little family

of colors.

Not long after I finished

knitting my cardi I heard of Amy Singer’s

call for design submissions for her upcoming

book No Sheep for You. I submitted photos

and was delighted when my design was accepted.

My B-cardi became Bacardi, out there in the

world for anyone to knit. But as you may

know, not everyone likes lime green.

It is one thing to

see a garment in a single color and imagine

it in another. It’s

like being in a store, seeing a lovely garment

and asking “Does this come in pink?” For

the knitter the answer is always “Yes,

if that’s the color you want”.

But what if you see a multi-colored pattern

you like, a garment you want to knit, but the

colors aren’t the ones that flatter you

and coordinate with your wardrobe? How would

you go about picking six new colors to knit

Bacardi?

Unfortunately there

is no scientific process or magic formula.

Color is subjective, and there are no right

or wrong answers. One person’s

winning combination may well contain another’s

least-liked colors. In the end, the “right” color

combination is the one that most pleases you,

or the lucky recipient of your knitting efforts.

So how should you tackle

the problem of knitting Bacardi in another

color palette? For a start, you can rest

assured that you will have no shortage of choices.

The yarn I used, Super 10, is available in

more than a hundred colors. I know some knitters

who like cool greens and blues, so let’s

look at a portion of Bacardi’s chart

and try substituting some colors. Because

the original colorway used an analogous color

scheme (which means that the colors are adjacent

or fairly close to each other on the color

wheel) we will stick to blues and greens

to start with.

If you search Knitty’s

archives you will find some excellent articles

about color theory. Here is a quick review

of the three terms used to define the properties

of a color: hue, value and saturation.

• Is it red, green, or blue? You are

talking about hue. Imagine a rich crimson and

a pale pink mixed from the same red — they

have the same hue.

• Is it light

or dark? You are talking about value. The

pale pink and crimson have the same hue but

the pink is much lighter in value.

• Is it pure, intense color like an artist’s

paint right out of the tube, or has grey,

white or black been added? Saturation is

also referred to as intensity, purity or

chroma. Besides being lighter in value, the

pale pink is also much less saturated because

it contains lots of white.

In this process of creating

a new colorway, we will, naturally, be changing

the hues. Do not worry too much about saturation.

If you love bright, intense colors you may

find that all six of the colors you will

choose are highly saturated, but subtle,

muted or “dusty” colors

are beautiful too and might find a place

in your colorway. Value will be an important

consideration for each yarn chosen. It doesn’t

matter if each color we choose has the same

value as the color it replaces in the original

chart, but all the new colors should be placed

in the chart according to their values relative

to each other.

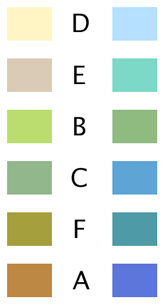

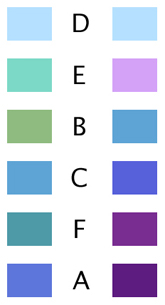

Here

is a representation of the six original colors,

arranged from lightest to darkest ---> Here

is a representation of the six original colors,

arranged from lightest to darkest --->

For color D we need one color that is lighter

than all the rest to provide the highlight

of the palette. The lightest color in the original

chart is Maize, a pale creamy yellow. The darkest

color, A, is Gold; it has the same hue, yellow,

but is darker in value. To imitate this relationship

in our new colorway [below] we will use a pale

blue as D, the lightest color and a periwinkle

blue as A, the darkest. There are many darker

blues, and nothing wrong with choosing one

of them, but keeping our darkest color relatively

light will copy the look of the original design.

In the original palette,

color B is Granny Smith, a light, saturated

lime green which accents the other colors.

Not a rule, but a suggestion: don’t be afraid to include

one color that is a bit different, and maybe

not your favorite. This color represents less

than 14% of the stitches in the chart. You

will never see a lot of it, but it can spice

up the color mix if there is one that is a

little brighter, warmer, or cooler than the

others. In our new colorway, B becomes Sage

Green. It isn’t more saturated than the

others, but it is the warmest. It appears to

be a warmer green in the context of the cooler

blues and turquoises than it does on its own.

For the three remaining

colors, E should be “relatively

light”, C “medium” and F “relatively

dark”. In place of the original Flax

[E], we’ll

use a turquoise that is fairly light but still

holds its own against the lightest blue. The “medium” [C]

is an in-between blue in place of the original

Sage Green, and “relatively dark” [F]

is a darker blue-green instead of the original

Peridot.

Here

is how the colors compare, from light

to dark... Here

is how the colors compare, from light

to dark... |

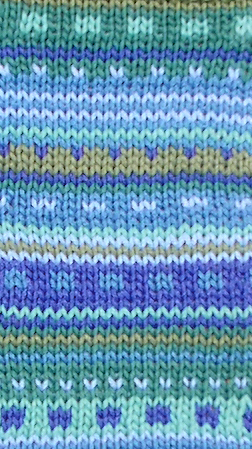

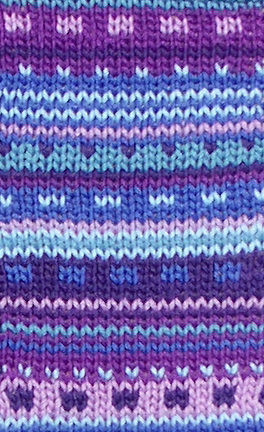

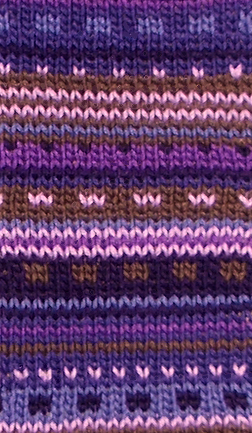

...and

here is a swatch in our new blue-green colorway.

|

|

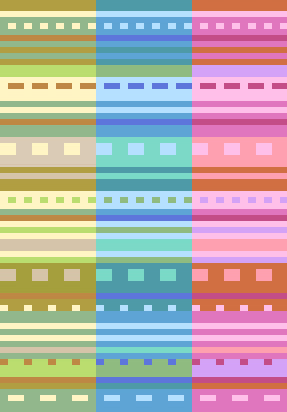

Let’s

look at another example in which the

values are again similar to the original

but the hues have been changed -- this

is sunset.

|

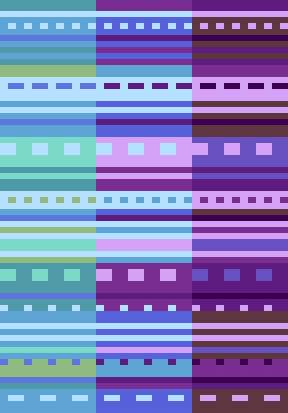

|   Looking

at a portion of these new charts next

to the original one [on the left of the

three], it is clear that the lightest

and darkest stripes and dots play the

same role in each version. The contrasts

between the other colors are not identical,

but the look of the original design has

been maintained. Looking

at a portion of these new charts next

to the original one [on the left of the

three], it is clear that the lightest

and darkest stripes and dots play the

same role in each version. The contrasts

between the other colors are not identical,

but the look of the original design has

been maintained.

|

This doesn’t

mean you must restrict yourself to light

colors. Perhaps you

would prefer to have some purple with

your blues. Let’s remove the green

and turquoise yarns from the blue-green

colorway and add three purples: a light

lilac, a bright intense purple and a

darker purple. The three blues used in

the blue-green colorway remain, but they

will not necessarily go in the same places

in the chart. The pale blue is still

the lightest color, so it remains as

D, but two of the purples are darker

than the blue that was formerly A, our

darkest color. |

Here are the colors,

again from lightest to darkest. Here are the colors,

again from lightest to darkest.

|

There is now more

contrast in the pattern because there

is a bigger range of values from lightest

to darkest -- this is blue-violet.

|

|

|

Now

we’ll change a few of the colors

again. The three blues are replaced by

two more purples and mocha brown. The

light lilac is now our lightest color,

so it becomes D, and what was previously

the darkest purple moves to F, to make

room for an even darker plum in the role

of A. Call this one purples.

|

The overall tone

of this colorway is darker than the others,

but the colors are still placed in the

chart according to their relative values.

|

When choosing colors, be aware of the way

a color can change depending on what other

colors surround it. You might pick up a cool

purple to put with some reds and find it now

looks more blue than purple. The best way to

predict how your six colors will work together

is to physically put them together. You might

try winding several strands of different colored

yarns around a finger and squinting at the

result to see how you like the effect. Of course,

the way to know for sure is to knit a swatch.

Some knitters may be wondering about the

software I use for these charts. It is Stitchpainter,

by Cochenille. I find the interface clunky

and the application’s lack of sophistication

can be frustrating at times. However it is

a great help to be able to take a chart like

this one, and with one click change every stitch

of pale blue to lilac. This software is a useful

tool for experimenting with colors in a chart.

What happens if we try pinks with purple rather

than blue? Or reds instead of pinks?

Obviously, the options are almost endless and

this can be daunting. If you are looking for

inspiration, notice the colors in a favorite

piece of artwork, a printed fabric or a hand-painted

skein of yarn. If you can get to a yarn shop

with a good selection of colors, take your

time and find a spot in good light, preferably

natural daylight. Get out skeins of all the

colors you think might work. Try starting with

a dark, a light and a bright, and then switch

the skeins around until you find six that work

together to make your heart smile.

|