Ravellings on the knitted

sleeve -- Part I

To some knitters or would-be

designers, there is nothing so daunting as

designing a knitted sleeve that fits.

The problem with sleeves

-- whether the simple, boxy drop-shoulder

style, or those involving more intricate shaping

-- is that there always seems to be a whiff

of uncertainty about the finished product.

First, there's uncertainty

in length. A knit garment body that winds

up being an inch too long or short can be

camouflaged or forgiven, unless you're particularly

fastidious. But a long sleeve that misses

the wrist by an inch is an aggravation, especially

if it was knit from the wrist upwards. Knitting

the sleeve from the shoulder down to the wrist

makes lengthening or shortening easier, but

you may not get an accurate measurement of

the sleeve length until you have bound off

and blocked the sleeve.

And then there's the uncertainty

in determining a proper upper arm width. Both

a too-narrow and a too-wide sleeve can be

uncomfortable.

|

Armscye?

In

sewing, the opening in the garment body

through which the arm protrudes is called

the armscye (pronounced "arm's eye"),

which is a somewhat more graceful word

than the "armhole" used in knitting.

|

Finally, there's the uncertainty

of armscye depth. How much space do you need

to allow freedom of movement for the wearer's

arm? How shallow can you make an armhole without

uncomfortably binding the shoulder? Knitted

fabric, having some inherent stretch, can

accommodate a slightly snug fit, but hand

knitted fabric cannot compensate for gross

misjudgment.

So, if you're in the position

of having to add sleeves to an existing sleeveless

vest or top, or designing a garment from scratch,

how do you pick the right sleeve style, and

how do you crunch the numbers to make the

sleeves fit the body?

To answer these questions,

you'll need to be acquainted with the common

types of sleeves used for clothing, and what

measurements to take. In this issue, we'll

look at different types of sleeves and their

respective pros and cons, and then discuss

measuring and designing the simplest species

of sleeves: drop shoulder and modified drop

shoulder sleeves.

Drop

shoulder

What it looks like

The drop-shoulder style has the simplest

lines of any sleeve style. The body of the

garment is usually a simple rectangle, with

little, if any, shaping. The body width (the

rectangle width) extends past the actual shoulder

line of the wearer; in fact, if no sleeves

were added to the drop-shoulder body, the

shoulder portion of the garment would extend

into cap sleeves. The armscye is not shaped

at all.

The sleeve is also based

on a simple rectangle, usually with a taper

towards the wrist. The sleeve is shorter than

the wearer's actual arm; the upper edge of

the sleeve does not reach the shoulder. The

length of the upper edge of the sleeve equals

two times the depth of the armscye. Once assembled,

the sleeve extends from the garment body at

a right angle.

|

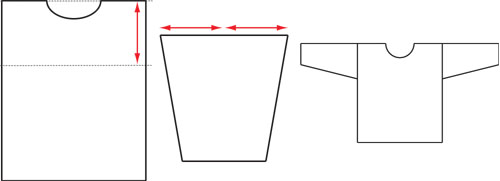

| A schematic

of a drop shoulder garment. When assembled,

the garment is distinctly "T" shaped,

and needs lots of wearing room [ease]

to fit properly. |

Assembly

If the garment is knit flat (i.e., with

the body in two pieces, a front and back),

a drop-sleeve pullover is assembled by first

seaming or joining the shoulders of the front

and back body, then centering the tops of

the sleeves with the shoulder seams, and sewing

or grafting the sleeves to the body. The whole

body is then folded in half at the shoulders,

and the side and sleeve seams sewn.

Alternatively, once the

shoulders are joined, the sleeves may be picked

up along the side edge, centered around the

shoulder seams, and knit down towards the

wrist. This eliminates some guesswork about

the length of the sleeves, since the garment

can be tried on before the cuffs are bound

off. (Of course, proper measuring and gauge

measurement techniques would eliminate this

guesswork as well, but picking up and knitting

downward also eliminates the armscye seam.)

The drop-sleeve garment

is also found in Norwegian-style sweaters,

typically worked in the round. If the entire

body is knit in the round, the armholes may

be cut and fixed afterwards using steeking

techniques. Otherwise, the upper body

may be split into two at the armholes, and

worked flat so that cutting is not necessary.

The shoulder seams are then joined, and the

sleeve is picked up all around the armhole

and knit in the round towards the wrist.

Pros

Because all seamlines are straight, this

style is easily adapted to be worked flat

or in the round.

The simple shape of each

piece makes for the easiest arithmetic

in calculating increases, decreases, and sleeve

length. The simple shapes also make it easy

to knit from the top down (shoulder to

wrist/hem) or bottom up (wrist/hem to shoulder).

The simple shapes also make

it easy to centre colour or texture patterns

without concern for interruptions. As

there is no armscye indentation, vertical

cable panels or colour designs can flow uninterrupted

along the edges of the front and back. That's

one reason you'll find many Aran-style sweaters

take advantage of the drop-shoulder style,

or its variant, the saddle shoulder. The only

concern you may have with a vertically repeating

pattern is ensuring that the repeats are not

cut off at an unattractive point.

|

| Vertical

designs flow uninterrupted on a drop shoulder

garment; pay attention to where a pattern

repeat falls on the sleeve. |

Because the seam between

the sleeve and body is not intended or expected

to lie at the shoulder joint, the drop shoulder

style "forgives" an imprecise fit

at the upper body.

Cons

Some people feel the lower armhole seam looks

untidy. The drop shoulder can evoke visions

of oversized, sloppy sweatshirts, because

for the most part, drop-shoulder sweaters

are quite loose-fitting.

The drop-shoulder style

can also make the wearer appear broader

than he or she actually is. This is partially

due to the fact that the garment is likely

quite loose-fitting, but also because the

seam between the sleeve and garment body is

almost horizontal, drawing the eye across

the body. (If the sleeves are eliminated,

as in a cap-sleeve garment, the extended shoulder

of the cap sleeve will also draw the eye across

the body, again producing the illusion that

the wearer is wider than he or she really

is.)

Although the sleeve meets

the garment body at a right angle, the wearer

rarely maintains a scarecrow stance with arms

extended from the torso at ninety degrees.

When the wearer stands naturally, with arms

down at his or her sides, this means that

fabric may bunch up in the underarm area,

resulting in discomfort.

Drop shoulders are also

generally unsuitable for tight-fitting

or close-fitting pullovers. We'll explore

the reason why in more detail in next issue's

article on set-in sleeve shaping; but briefly,

when the wearer's arm is extended, the distance

required to travel from the neck, over the

shoulder, and down the arm is shorter than

when the arm is hanging straight down. When

the arm is lowered, there must be sufficient

ease in the garment upper body to cover that

extra length in the shoulder. In a drop-shoulder

style, that ease comes from a wider body.

Not only that, but a tight,

rectangular body just looks and feels uncomfortable.

Trust me.

Also, thanks to the generally

loose fit of drop-shoulder garments, a short

sleeve (or cap sleeve, if the sleeve part

of the garment is eliminated) is likely

to reveal foundation garments or less attractive

body parts when the arm is raised.

Variations

The disadvantage of an "untidy" appearance

or feel can be eliminated by substituting

a modified-drop-shoulder style, which

indents the upper part of the armhole seam

on the body to more closely resemble a shaped

armscye. The armscye seam may not rest exactly

at the shoulder line, but it is at least closer

to the shoulder.

|

| A schematic

of a modified drop shoulder garment. When

assembled, the lines are similar to the

drop shoulder style. |

The disadvantages of a tighter-fitting

drop-shoulder garment can be alleviated by

imcorporating an underarm gusset,

which is used on traditional fishing ganseys.

The gusset is a diamond-shaped insert that

provides the extra ease necessary for natural

arm movement. Since it is usually formed by

adding extra increases to the body and sleeve

at the underarm, it doesn't have to look like

a diamond or an insert, but it can be

decorated to look like one if desired.

Another variant of the drop

shoulder, often used in combination with the

gusset on gansey-style sweaters, is the shoulder

strap. The strap is an extension of the

sleeve along the shoulder; the front and back

of the sweater are joined to this strap, rather

than to each other.

|

| The schematic

for a gansey style. On the left side,

the shaping of an armhole gusset; on the

right, shoulder strap shaping. The neck

end of the strap may be widened to provide

a more accurate shoulder fit. |

If the sleeve extends from

the rectangular body at a right angle with

no seam, then the sleeve is a kimono sleeve.

When knitting a kimono sleeve, the assembly

method is similar to the dolman or batwing

sleeve, described below.

Set-in

What it looks like

The set-in sleeve style appears to

have simple lines when assembled, but the

shaping of the individual pieces is more complex

than the drop shoulder. The shoulder area

of the garment body is cut out so that the

whole arm is exposed. The armscye begins at

the side seam and curves towards the body

in a gradually increasing slope (in other

words, beginning with frequent decreases,

followed by less frequent decreases), until

the armscye line is more or less vertical.

The armscye edge does not extend past the

wearer's shoulder, unless the shoulder is

intended to be filled out with a shoulder

pad, or the garment is intended to be worn

over other layers, such as a coat or jacket.

The sleeve tapers from the

bicep line to the wrist. Above the bicep line,

the sleeve cap gently slopes to the shoulder

point. In knitting, the uppermost point is

actually a bound-off edge, between two and

four inches long.

The perimeter of the sleeve

cap is approximately equal to the total perimeter

of the armscye, which is greater than twice

the armscye depth (unlike the drop shoulder).

The height of the sleeve cap is less than

the depth of the armscye. Sometimes, the sleeve

cap perimeter is longer than the perimeter

of the armscye. In that case, excess fabric

can be gently eased in while sewing the armscye

seam.

When assembled, the sleeve

extends from the garment body at an angle

significantly less than ninety degrees, which

is closer to the usual position of the arm.

Often, knitted garments are designed so that

the sleeve cap and front and back armscye

are symmetric; in reality, our bodies aren't

that symmetric, but the stretch in knit fabric

allows for this tiny cheat.

|

| The

schematic of a set-in sleeve garment.

When assembled, the angle between the

sleeve and body means less fabric bunches

under the arm, and a sleeker fit is possible. |

Assembly

Because of the shaping of the armscye and

sleeve cap, a set-in sleeve garment is usually

knit flat. The front and back body are joined

at the shoulders, and then the sleeve cap

is sewn into the armscye. Because a curved

edge is being matched to a (mostly) straight

edge, neat sewing is sometimes a challenge.

If necessary, any excess fabric along the

sleeve cap should be eased (slightly gathered)

to fit the armscye. Once the sleeve cap is

sewn in, the body side seams and the straight

sleeve seams are sewn.

Alternatively, the front

and back body first may be joined at the shoulder

and side seams, and the sleeve sewn into a

tube along its long seam. The sleeve is then

set into (hence the name, "set-in") the armscye,

matching the underarm seams together and the

centre of the sleeve cap with the shoulder

seam. This is usually the order of operations

used in sewing. In knitting, you'd use this

assembly method if the lower part of the body

was knit in the round, then divided for knitting

and shaping the upper body.

It is possible to pick up

and knit a set-in sleeve from the armscye

down to the wrist, but this technique will

require short rows to give the sleeve proper

shape.

Pros

Because it more closely mimics the wearer's

usual arm position, the set-in sleeve overcomes

the main disadvantages of the drop shoulder:

no fabric bunching in the underarm area, making

for a more comfortable fit, and vertical

armscye seams instead of horizontal seams,

which promotes a more slimming

look.

The shaping of the sleeve

cap provides the necessary "space" in the

garment's upper body required to allow for

freedom of arm movement, without having to

add extra room to the garment body in a manner

similar to the drop-shoulder style. This means

that the set-in sleeve style is suitable

for tight-fitting or close-fitting tops.

It's still good for looser clothing, as well.

If the sleeve is set into

a short-sleeved top, the closer fit around

the arm and shoulder means that raising one's

arm does not reveal any, ahem, unappealing

features.

Cons

The shape of the sleeve cap makes this sleeve

the most labour-intensive to calculate

and to sew to the garment body.

If the garment body is designed

around vertical panels, then vertical

designs will have to be interrupted or eliminated

in order to accommodate the indented armscye.

|

| Vertical

designs near the body edge will be interrupted

by the armscye shaping of a set-in sleeve

garment. |

Upper body fit is more important

with a set-in sleeve garment; when choosing

a size, care must be taken to ensure that

the finished shoulder width will fit the wearer.

If the garment's shoulders are too narrow,

the sleeve cap will have to stretch over the

wearer's shoulder; if the garment's shoulders

are too broad, they may result in an odd,

boxy profile.

Variations

Set-in sleeve garments may be combined with

gussets for a better fit, and shoulder straps

for a decorative look. The sleeve cap alone,

or the entire sleeve, may be enlarged to add

details such as a gathered cap or a shoulder

pleat.

Normally, the sleeve and

body are joined at a seam at or very near

the shoulder line; depending on current trends,

the seam may be extended beyond the natural

shoulder line (often requiring the use of

shoulder pads to fill out the shoulder area),

or cut slightly inwards (a "narrow shoulder"

look that was more popular in the late 1970s).

A summery variation of the

set-in sleeve is the use of a sleeve cap alone

to cover the shoulder, leaving most of the

upper arm bare.

|

| The tiniest

of set-in sleeves. |

Raglan

What it looks like

The raglan style is often associated

with a casual or sporty look. Instead of positioning

an armscye seam over the shoulder, the raglan

sleeve seam slants from the underarm to the

neckline, with the result that the back, front,

and sleeve all taper towards the neck. Depending

on the garment design, the upper edge of the

raglan sleeve may form a substantial part

of the neckline, and may be shaped to blend

in with the curve of the front and back neckline.

Usually, the raglan seam

edges on the front, back, and sleeve are straight

lines, as they are formed by decreases (or

increases, if knit from the top down) at regular

intervals. Occasionally the seams may be curved

either as a design feature, or as a tweak

to fit in the correct number of decreases

before running out of upper body or sleeve

rows. The length of each raglan edge on the

sleeve is approximately equal to the length

of the corresponding raglan edges on the front

and back, although it is possible that the

sleeve edges may be a little longer, in which

case any excess fabric may be eased in gently.

When assembled, the sleeve

usually extends from the garment body at an

angle less than ninety degrees, but not as

small an angle as the set-in sleeve. The pitch

of the raglan seams determines the angle at

which sleeve and body meet. For example, it's

possible to have a raglan sleeve that extends

at a right angle from the garment body, if

the seams are angled at forty-five degrees

from the vertical.

|

| Schematics

of a raglan sleeved garment. The angle

at which the sleeve meets the body depends

on the pitch of the raglan shaping on

both the sleeves and the body. |

Assembly

If the garment is knit in flat pieces, the

front, back, and sleeves are first knit. The

garment is assembled by sewing the front raglan

edges of the body to the front raglan edges

of the sleeves (if the sleeves are not symmetric,

the front raglan edges of the sleeves will

usually be shorter than the back edges), then

sewing the back raglan edges of the sleeves

to the raglan edges of the back body. The

underarm and side seams are sewn last.

If the garment is knit in

the round from the bottom up, usually the

body and sleeves are first worked separately

from hem (or cuff) to the underarm. The live

stitches of the body and sleeves are then

threaded onto a long circular needle, with

the live stitches of the upper sleeves lying

between the live stitches of the upper front

and back. Some underarm stitches on both the

body and sleeves are left on holders or waste

yarn. The upper body, with raglan decreases,

is then worked in the round up to the neck.

Because knitting in the round will yield a

front and back neck of the same depth, often

short rows may be added to the back to raise

the back neckline by about an inch or so.

The underarm stitches are then grafted or

bound off together.

If the garment is knit in

the round from the top down, the raglan lines

of the upper body are shaped using increases,

rather than decreases, to the bottom of the

armholes (as with knitting from the bottom,

short rows may be worked across the back to

raise the armhole). At that point, the sleeves,

front, and back must be divided out to separate

circular needles, double-pointed needles,

or holders; the front and back on one set,

and each sleeve on their own set. When the

body is worked using the front and back stitches,

additional stitches are cast on at the underarm

positions; similarly, underarm stitches are

added when the sleeves are worked downward

from the upper sleeve stitches. When the body

and sleeves are complete, the underarm stitches

are grafted or sewn together.

Pros

The lines of the raglan sleeve provide a more

sophisticated style than the drop shoulder,

while requiring only relatively simple

arithmetic. But like the drop shoulder,

the raglan style is also a forgiving shoulder

fit--there's no armscye seam to align

with the shoulder joint.

At the same time, the raglan

sleeve is easier to calculate and sew than

a set-in sleeve, while still providing some

of the same fitting benefits. Thanks to the

angled pitch of the arms, there's less

fabric bulk under the arms, and it's

not necessary to add as much extra ease

in order to fit the garment over the shoulder

area.

However, close and tight-fitting

raglans with shallow armholes may still be

uncomfortably tight, unless some other adjustments

are made to the shoulder area; for example,

by adding short row shaping at the shoulder

point to allow for movement. Alternatively,

the sleeve may be worked with extra wearing

ease up to the shoulder, with a sleeve dart

removing the extra ease once past the shoulder.

These alterations will provide a better fit,

but it does detract from the "forgiving shoulder

fit" advantage.

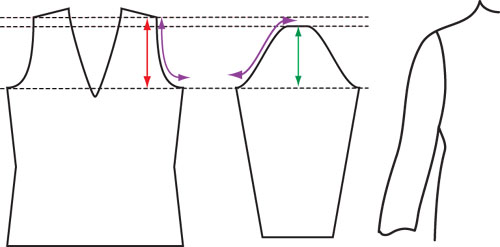

|

| Inserting

short rows at the shoulder point will

compensate for a tight fit under the arm;

additional decreases, creating a dart,

can also take up slack once the sleeve

meets the body |

The lines of the raglan make this style a

prime candidate for knitting from the

top down or knitting in the round, with

only underarm stitches to be grafted or sewn

together.

Also, either a pro or a

con depending on your point of view, the raglan

lines accentuate the shoulders, making

you look broader than you really are. This

aspect can be enhanced by working the sleeves

in a contrasting colour.

Cons

If the raglan sleeves extend from the garment

body at a ninety degree angle, or something

close to a right angle, then some of the same

fitting problems as for drop shoulder garments

will arise: excess fabric bunching under

the arms, and an unsuitability for

tight-fitting garments. That problem

can be alleviated by altering the pitch of

the raglan edges to something greater than

forty-five degrees.

Even non-right-angled raglan

sleeves may feel tight and binding in

a close-fitting garment, for similar

reasons as for the drop shoulder: there's

not enough room in the garment upper body

to allow for the curves of the shoulder.

Because of the sloped raglan

seams, vertical stitch or colour patterns

are interrupted. For example, the decreases

may interfere with an extra-wide central panel.

However, the decrease lines also provide an

opportunity for interesting design details.

If you're a busty body type,

there's a traditional caveat against the raglan

style. Whether you believe it (and whether

you think it's a pro or con) is up to you,

but some feel that the slanted lines of

the raglan sleeve call attention to the bust

area, highlighting an already ample figure.

Other people don't believe this, and argue

that it slightly diminishes the appearance

of the bust; both sides cite the slanted raglan

seams as the cause.

If you think it's a problem,

you can try working different decrease styles

to de-emphasize the seamlines, or use the

yoke sweater variation instead.

Variations

A construction method peculiar to knitting

is the yoked sweater, knit in the round. The

yoked sweater can be considered to be a graceful

adaptation of the raglan design, or vice versa.

In essence, the yoked sweater is raglan shaping,

distributed evenly around the shoulders and

chest, rather than concentrated at four seamlines.

Like the drop shoulder and

set-in sleeve, the raglan sleeve can be styled

with a shoulder strap. In that case, the "raglan"

portion of the sleeve ends sooner, and the

strap extends from the raglan portion to the

neck.

Dolman

What it looks like

The dolman style has a sleeve formed integrally

with the body, with only two substantial seams

at the underarms. A generous amount of space

is provided under the arms for movement, so

the garment is usually considered to be very

loose-fitting, even if the sleeve forearms

are tight.

Knitted dolman styles are

often designed as one-piece designs, to be

knit sideways (cuff-to-cuff) or continuously

from front to back. With this unitary construction,

the dolman sleeves almost invariably extend

from the body at a right angle. It is possible

to alter this shape to provide angled sleeves

with strategically placed increases and decreases

or short rows, or alternatively by working

the front and back separately.

|

| A dolman

sleeved garment schematic. With clever

shaping or short rows, the sleeves can

be angled. |

Assembly

Because of the shape of the pieces, dolman-sleeved

garments usually knit flat. If a dolman-sleeved

garment is worked from bottom to top in two

pieces, for both front and back the body is

worked from the hem to the underarm, where

the sleeves begin; stitches are cast on at

the end of a number of consecutive rows until

the number of stitches added to each side

of the body is equal to the length of the

sleeve extension. Once half the circumference

of the cuff measurement has been worked, the

upper edge is gradually bound off over a number

of rows (with neck shaping as required). If

a less tapered sleeve is desired, the sleeve

extension cast-on or bind-off rows could be

worked over fewer rows. The front and back

are then seamed along the underarms and over

the tops of the sleeve and shoulder.

If the garment is knit in

one piece from front to back (or back to front),

the front (or back) is worked in a manner

similar to the front (or back) of a two-piece

dolman garment, but it is not bound off at

the upper edge. Instead, the body on either

side of the neck is worked, with neck shaping

(decreases and increases) until the neckline

on the back (or front) can be completed. Extra

stitches are cast on in the middle of the

next row to join the body back (or front)

together; bind-off rows shape the lower edge

of the sleeve, and then the body is knit to

the back (or front) hem. To assemble, the

garment is folded together at the shoulder,

and the underarm seams are sewn.

If the garment is knit in

one piece sideways (cuff-to-cuff), the first

cuff is cast on, and increases shape the sleeve

until the body begins; extra stitches are

cast on at the end of two consecutive rows

to equal the length of the body extension.

When the depth for the neckline is reached,

stitches are decreased or bound off to add

the shaping; increases or cast-on stitches

close the neckline on the other side. Two

more bind-off rows create the body sides,

then the sleeves are gradually decreased to

the second cuff. To assemble, the garment

is folded together at the shoulder, and the

underarm seams are sewn.

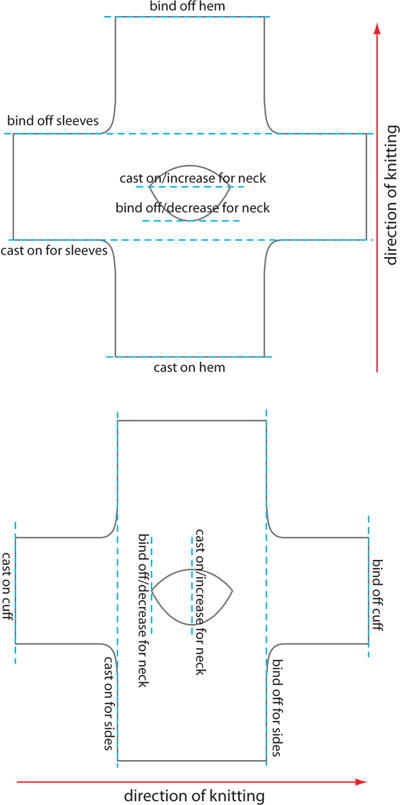

|

| The order

of construction for a one-piece dolman

sweater, from hem to hem or side to side. |

Pros

As noted above, if you're a fan of sideways

knitting, the dolman is perfect for a

cuff-to-cuff sweater.

If you choose to knit the

garment with the front, back, and sleeves

as a single piece, it's also the simplest

style to assemble, with only two underarm

seams to sew. This makes it an excellent choice

for lacy or holey fabrics (think novelty ladder

or confetti yarns) that just don't seem to

take seaming gracefully.

Dolmans also provide for

continuity of pattern from sleeve

to body, if the garment is knit sideways (there

will be an interruption at the neckline),

or over the shoulder, if the garment is knit

from front to back.

The dolman sweater is easy

to fit for similar reasons as the drop

shoulder, as there is no cross-shoulder seam.

Cons

If you choose to knit the front and back separately,

there will be a seam or join from the

wrist to the neck. This is usually not

a desirable construction technique in knitting,

from the point of view of finishing. In an

otherwise plain garment, that seam will become

a focal point.

If the front, back, and

sleeves are knit as one piece, the unitary

construction means that there is no shoulder

seam to support the weight of the fabric hanging

down from the shoulders. This may result in

pulling and stretched stitches in

the shoulder area. Unitary construction also

means that there will be a lack of symmetry

in the knitted design. Knit stitches, having

a "V" shape, have only one axis of symmetry.

As the stitches march across your body from

side to side, the "V"s will only point in

one direction. If you knit the garment from

front to back, then the stitches will be right

side up on the front, and upside-down on the

back. This is a minor inconsistency, but it's

more noticeable with ornamentation that highlights

the shape of the knit stitch, such as Fair

Isle or intarsia.

Knitted dolman designs are

usually constructed with sleeves extending

at right angles to the body, so once again

there's the problem of too much fabric

bunching under the arm, leading to a

top-heavy appearance.

Variations

Carrying the dolman style to the extreme,

the batwing is almost a poncho with

two extra seams. It's dramatic, and best suited

to a fabric that drapes and folds well.

|

| A dolman

sleeved garment schematic. With clever

shaping or short rows, the sleeves can

be angled. |

Now that you're acquainted

with the various species of sleeves, how do

you pick the right one? Consider the pros

and cons of each type of sleeve, keeping in

mind your objectives in fitting the recipient

and (if you're designing your own garment)

design planning.

For example, if you're knitting

for someone else and you don't know the recipient's

actual size, the safest styles are the types

that can be knit from the top down to allow

for easy length adjustments, and that don't

require a specific cross-shoulder measurement:

the drop shoulder and raglan sleeve are best.

If you want a sleek, long-sleeved

top that can slide underneath other jackets

or sweaters, you need to minimize bulk under

the arms. Pick the set-in sleeve or a close-fitting

raglan or yoked design. These styles are also

best if you want to knit a body-conscious design,

with a nipped-in waist; waist shaping is lost

on loose-fitting garments.

In general, when you're concerned

with a good fit that complements the wearer

(as opposed to a "safe" fit that will accommodate

a small range of body sizes), set-in sleeve

styling is almost uniformly an ideal solution

to the problem of adding sleeves to a garment.

It works just as well for close-fitting tops

as for loose-fitting pullovers; it has style

lines that are friendly to most body types;

it requires minimal alteration to a pre-existing

sleeveless design; and a well-sized set-in sleeve

is always comfortable, with minimal fabric bulk

under the arm.

However, if your intention

is to incorporate a particular design feature,

such as colour or texture or a different construction

method, other styles may be more suitable. If

you want to preserve the lines of a vertical

or panel design, then a drop shoulder is your

best bet. If you want to knit a garment sideways

(cuff-to-cuff), the drop shoulder or dolman

style is the easiest way to go. And if you want

to knit everything in the round, with a minimum

of picking up, grafting or sewing, the yoked

and raglan styles would be your first choices,

requiring just a bit of grafting or picking

up at the underarm. Next best are the drop and

modified drop shoulder, with sleeves that can

be picked up from the armhole and knit down

to the wrist.

Adding a drop shoulder

or modified drop shoulder to a garment

To ease into sleeve design,

let's consider the most basic body and sleeve

shape. If you've got a loose-fitting vest

pattern, it's easy to design drop or modified

drop shoulder sleeves to fit.

If you feel a surge of panic

when you see the length of the discussion

below, don't worry! The actual steps are quite

simple. If they were reduced to algebraic

expressions, this discussion would in fact

be quite terse. However, as we are seeking

to postpone the introduction of algebraic

expressions until absolutely required, these

instructions are necessarily quite verbose.

If you can't bear to read on, skip

ahead to the précis.

Begin with taking

measurements

Usually, a vest has an

indented armscye; if the vest were shaped

like a plain rectangle, a flange of fabric

would extend over the shoulders. (Such vests

have been known to exist, so we won't ignore

them.)

|

| Typical

vest shapes: from left to right, with

a curved armscye; with an angled armscye;

with a box-shaped armscye; and a plain

rectangular body. Note that in a plain

rectangular body (which would result

in a true drop shoulder style), the

upper body width is the same as the

lower body width |

From the vest design,

you should be able to work out some basic

dimensions that will affect your sleeve

design: