|

or : One pound of fiber, two fiber artists,

three yarns, and four colors.

In this article we

plan on demonstrating how your dyeing is akin

to your 'signature' or your fingerprint. Two

fiber artists, given the same tools, using the

same method, can wind up with very different

results.

|

Materials used

by Symeon and Amy for dyeing

- Safety gear

- Fiber -- one pound

of domestic wool top

- Jacquard dyes

- Acid mordant --

white vinegar

- Dye mixing containers

and utensils

- Synthrapol

- Roasting pan --

enameled turkey-type roaster with lid

- Oven

- Sink for rinsing

|

Here's an overview of

our dye process.

We start out by soaking our fibers for about

a half an hour in enough warm water to completely

cover them. Then gently strain the excess water

out. (Try to handle your wet fibers as little

as possible, to avoid neps or other damage like

felting.)

We both used the same 4 colors

of Jacquard acid dyes, purchased from Dharma

Trading.

yellow #601

emerald #629

navy #626

purple #613

Although, the name "acid

dyes" sounds pretty ominous, the only time

they pose a danger are when they are in powder

form.

|

Dyeing Safety Tips

- Use tools for dyeing

only, do not use any tools (pots, utensils

etc) that will be used for food later.

The oven and sink don't count

- use dyes in a well

ventilated area,

- wear a dust mask

when mixing dyes

- keep pets and children

out of the room

- use rubber gloves

- protect the surfaces

that you'll be dyeing on (newspapers

are good)

- wear old clothes

and shoes

|

Employing some simple

precautions, such as using dyes in a well ventilated

area, keeping pets and children out of the room,

wearing a dust mask and rubber gloves, are strongly

suggested.

It's also a good idea to not use the dye pot or

utensils used for mixing or applying dyes for

food.

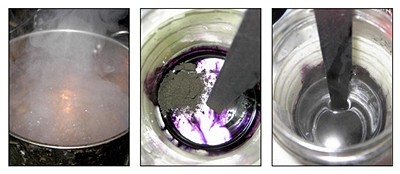

We begin mixing our dyes by creating a slurry

out of very hot water and our dye powder, by adding

adding just enough hot water to create a paste

and dissolve all the powder.

How Hot is Very Hot Water?

Since each color has

its individual 'strike point', or temperature

that it must reach to grab on to the fiber,

in our experience, anything with red or yellow

in it will take more heat to strike. For example,

blue will dissolve to its even color at a lower

temperature than green. So, bring your dye-mixing

water to a boil.

Once completely dissolved,

we can finish making our dye mixture by adding

more water and our acid. We use white vinegar,

approximately one part vinegar to three parts

water.. White vinegar or citric acid crystals

are preferred mordants. If you are using citric

acid crystals, dissolve them before adding them

to your dye mixture.

Hard Water?

If you have hard water,

it will affect your dyes. There are dyeing-specific

water softeners out there, some of which are

toxic and require more precautions. Sodium

hexameataphosphate is sold by many suppliers,

including Dharma Trading. (You can use this

in your soak and/or dye mixture.) Please follow

the directions on the label.

The amounts of dye powder

that you use will affect the outcome of your

product. You can use very little for a light

effect or quite a bit for more intense color.

However, there is a point where your wool cannot

take any more dye. It will use what it can and

the rest will be wasted. The goal is to not

waste dye and to have what you use be fully

exhausted [that means it's absorbed by the yarn,

leaving clear water behind].

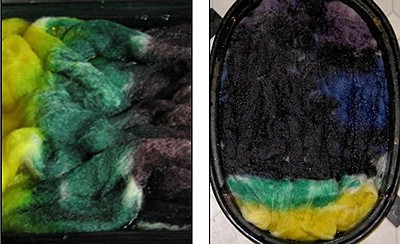

Gently placing our damp wool

in our enamel roasting pans, we apply color.

You can either transfer your dye into a squirt

bottle, or pour on your dyes directly from the

containers you mixed them in.

When satisfied, we set the

dye with heat.

Place in the oven at 250F.

for about 30 minutes. (This time and temperature

was a compromise, as one of us sets our dyes

at 300F for 20 minutes while the other sets

at 200 for 45 minutes.) Most dye manufacturers

claim that most of the color should be absorbed

within the first 20 minutes.

Remove roasting pan from

oven and let cool completely (back to room temperature).

Then remove it from the roasting

pan, and gently place it in a colander to strain

out excess liquids. Rinse gently to remove any

dye and mordant that remains. A dash or two

of Synthrapol will ensure that any unfixed dye

will come out. But be very careful during this

step -- this is when most people accidentally

felt the roving. (Always remember that the key

ingredients for felting are soap, warm/hot water,

and agitation.)

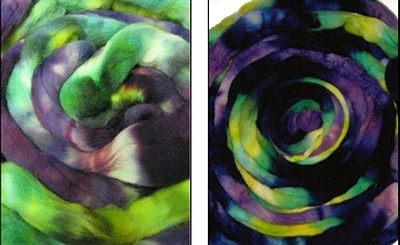

Now that the dyeing is done,

the rovings don't seem to be dramatically different.

The divergence in overall tone is spectacular,

as one appears to be more "green"

and the other more "blue" (or one

is lighter and one is darker).

While both samples take advantage

of controlled color bleeding, one incorporates

the principles of negative space in its scheme

(Amy), while the other is fully dyed (Symeon).

But let's look at what happens

when we start spinning. The contrasting values

are highlighted when the wool is spun into yarn,

and altered even more when the wool is spun

to various weights and particular styles.

With this, we also hope to

demonstrate how to change the characteristics

of a dyed top to suit your wants and needs.

(If you haven't heard it, or experienced it

for yourself, we'll repeat it here.... the most

'eh' dyed fiber, can turn into the most jaw-dropping

yarn if spun into what it wants to be. Sadly

this can also work in the reverse.)

First up, our bulky thick-and-thin

single.

Both spinners took slightly

pre drafted fibers (about pencil sized strips)

and spun them at a low TPI/twist angle, with

regular intervals of slubs. These yarns don't

stray too far from the individual roving much,

and the color changes remain intact. Although,

with the yarns sitting side by side, the deviations

start to pop out at us. The use of negative

space in the yarn on the left is now in sharp

contrast with the fully dyed yarn on the right.

Next, our 'high-low' 2 ply.

Here, both yarns are composed

of one high-twist smaller single and a low-twist

larger single. This application manipulates

the color properties by distributing the colors

to bring more balance to the overall tone of

the yarn. It also adds a new dimension of texture.

(The alteration of the textural landscape will

be more apparent when worked into a fabric --

but that's another story.) This method is good

to use when you are after accents, rather than

a complete departure from your bulky single.

Last, but not least, our

balanced 2-ply DK wt.

For these yarns, two (relatively)

higher twist, evenly spun singles are plied

together. This traditional plying method ensures

a more thorough distribution of color. The tones

of both yarns have changed radically. The orientation

of the colors works with (and against) themselves

to create a new layer of color. (A simple example

of this principle is to ply a solid red single

with a pink or white single. It will considerably

'lighten' your yarn & subsequent fabric.)

This arrangement often gives a very nice "tweed"

effect.

We hope that we provided

some food for thought with this brief examination.

Not only does an individual fiber artist have

their own distinct way with colors, applied

and articulated in a style as unique as their

fingerprint, but, there are many ways to utilize

a small palate, including incorporation of negative

space, color bleeding, the size of one's drafting

zone, and the distribution of color through

plying techniques. |