Okay,

for a few months now you've been dabbling

in Kool-Aid

dyeing, and love the feeling of creating

your own colors. But what if you don't like

candy colors? What if that sickly sweet smell

makes you gag, or makes your cat drool? You,

as an ordinary individual, have access to

a hundred years of chemical research, and

you can use exactly the same dyes as industry

does - the ones where the fabric will shred

decades before the colors fade. Better yet,

you may want to use animal-protein fibers

as a substrate, not just wool and silk but

luxury exotic stuff from cashmere to possum.

These allow you to use acid dyes, possibly

the easiest ones ever invented. In fact, they

pretty much work like Kool-Aid, which is where

assiduous Knitty reading is its own reward.

Okay,

for a few months now you've been dabbling

in Kool-Aid

dyeing, and love the feeling of creating

your own colors. But what if you don't like

candy colors? What if that sickly sweet smell

makes you gag, or makes your cat drool? You,

as an ordinary individual, have access to

a hundred years of chemical research, and

you can use exactly the same dyes as industry

does - the ones where the fabric will shred

decades before the colors fade. Better yet,

you may want to use animal-protein fibers

as a substrate, not just wool and silk but

luxury exotic stuff from cashmere to possum.

These allow you to use acid dyes, possibly

the easiest ones ever invented. In fact, they

pretty much work like Kool-Aid, which is where

assiduous Knitty reading is its own reward.

You may have thought professional

dyeing was a messy, mysterious and possibly

toxic process. Your hippie mother might have

destroyed a couple of washing machines trying

to support a tie-dye t-shirt habit in the

'70s. But this is likely due to using Procion-type

dyes, which work on cellulose/plant fibers.

They do require a non-plumbing-friendly environment,

enough salt to desertify a small town, and

washing out a lot of dye chemicals into the

sewers. The 'natural' dyes usually presented

as alternatives aren't much better. Not only

do they give pretty unreproducible colors,

they often involve poisonous or endangered

plants, and much of their use requires mordants

to set, a euphemism for toxic heavy metals.

On top of that, they often work slowly enough

that the smelly mess is left out for long

periods of time, inviting accidents from passing

kiddies or pets.

Acid dyes however are a

lot friendlier, both to you and the environment.

They are, of course, toxic in a long-term

carcinogenic kind of way; you

don't want to ingest them. But their bad effects

are mostly due to inhaling

them in powder form, just like Kool-Aid. If

you mix standard solutions in

water with reasonable precautions (outside,

out of the wind, with gloves and

mask on on) you're pretty safe from then on.

The solution can keep for weeks or months

in the fridge, so you can make enough of it

in calm, safe

conditions. Then all you need is to wear rubber

gloves, and to use separate

containers for your dyeing - not your cooking

pots. No dye will escape in

the air, even in the steam generated by simmering,

and if you wipe spills

promptly, it's easy to prevent newly dried

powder from getting airborne in

your kitchen. This is one of the things that

makes acid dyes so friendly to

apartment dwellers. All you'll be adding to

help the dye set is a bit of

ordinary white vinegar, which can even be

neutralized with a pinch of baking

soda before disposal if you're concerned about

a septic system. If you get

anywhere near the appropriate dye quantity

for your fiber, which is

recommended from an economical point of view

anyway, all the dye will

'exhaust' or be bound to the fiber, and you'll

only be pouring away

practically clear water. Doesn't all that

sound much better?

On

another level, while acid dyes seem proportionally

a bit more expensive than other types by weight,

if you consider that they're extremely effective

and don't require any extra chemicals, they're

actually one of the cheapest ways to go. Likewise,

any equipment you're likely to need is just

another set of cooking stuff, best acquired

at the local thrift shop. A cheap enameled

canning/stew pot (standard 3 US gallons) is

about right for a sweater's worth of fiber.

You might at most want a vegetable steamer

to put in there, some measuring spoons, and

I use disposable chopsticks recycled from

takeout adventures for stirring. The only

place where you might want to invest good

money is in your dust mask, and in brand-name

plastic: Saran Wrap (original) and Ziploc

bags will be easier to manipulate and will

not melt in the later stages.

As

in any other dyeing, you can start with fiber

in any form, as long as it's a protein fiber

-- that is, some animal was involved in the

growing.

As

in any other dyeing, you can start with fiber

in any form, as long as it's a protein fiber

-- that is, some animal was involved in the

growing.

Most knitters will

want to start with yarn, possibly very cheap

yarns in icky to horrifying colors from the

sales bin :-). But you can also start with

clean fleece or prepared roving, or dye a

finished product such as a sweater or fabric.

You can start with white and get anything,

or you can dye over natural-colored wool or

tussah silk for more toned-down effects. And

even more conveniently you can overdye other

colors. Which means there are NO mistakes

in dyeing - if you don't like the results

you simply add another layer of color till

you get something you like. The only caveat

is to start with lighter/ brighter colors

and work your way to the darker ones slowly.

And I'd also add a small warning peep from

the Voice of Experience about trying to mask

stains with dark dyes, even deep black ones

- it doesn't work.

You want to make some

attempt to weigh your dry fiber before you

start, because it determines the optimal amount

of dye you'll need. This doesn't have to be

very exact. You can take on faith the label

on yarn balls, you can use a postal scale

and add up smaller quantities, you can even

use a good bathroom scale and estimate the

difference between you weight and that with

the yarn. The reason is that you want to aim

for about 1-3 grams of dye per hundred grams

of dry fiber. You can use less if you want

a more pastel look or a subtle overdye, more

if you want intense colors, a mix of both

for more design interest.

The easy way to figure this out, if you don't

want to be dorking with esoteric, expensive

equipment like gram-scales, is via solutions.

If you make a 1% dye solution, one gram dye

per 100ml water, you can easily calculate

how much solution you need to get a certain

weight of dye into your fiber. The nasty trick

here is that the volume of a gram of dye varies

slightly by color, so do weigh accurately

if you can, but 2 teaspoons will generally

cover it. And do I need to mention that this

is one occasion where abandoning anti-metric

prejudices will really work in your favor?

Unless you're really into fraction masochism,

metric is your ticket to getting close to

the desired results even with relatively low-tech

equipment.

It's important that the fiber be thoroughly

wet before you start. And in animal fibers,

it's particularly important that fiber be

clean and de-greased. The best way to achieve

this, even if your fiber already looks clean,

is to soak it overnight with a shot of Dawn

dish detergent. You don't have to rinse out

the detergent as you dye, it doesn't interfere

with the dyeing process and in fact it might

help minimize fulling.

You can apply the dye directly in what's generally

called 'yarn painting'. You lay skeins out

on Saran Wrap. Then you can use sponges, stencil

brushes, gloved fingers or whatever strikes

your fancy to apply dye solution, diluted

with a bit of vinegar, in various colors and

patterns, working more or less hard to have

the dye penetrate the fiber as desired. Or

you can do one of my favorites and use syringes

to inject the dye directly into balls, which

gives small repeats well suited for knitting.

Whatever the method, the idea is to have several

colors work together and to slap the dye solution

on directly where you want it. Or you can

use better-known immersion methods, and get

a fairly uniform single color all over your

fiber, dunking it in proportionally large

amounts of water in a big pot.

The important point is that you need to not

only get the dye onto your fiber, but you

need it to chemically bind, to actually become

part of the fiber. This works best if you

use the twin secrets of acid dyeing: acidity

and heat. It doesn't take much acidity to

do the trick, the general rule is a glug of

vinegar per potful. That's right, a glug -

a scientific measurement of what happens when

you just tip the bottle. A small glug will

still work, perhaps not so well if you're

using very alkaline well water. A large glug

will work well if perhaps a bit too quickly,

and pure vinegar won't work any better. A

small point to remember here is that acidity

doesn't harm protein fibers, in fact slight

acidity is good for them. Remember how grandmas

used to rinse their hair with dilute vinegar

or lemon before commercial conditioners came

about?

The important point is that you need to not

only get the dye onto your fiber, but you

need it to chemically bind, to actually become

part of the fiber. This works best if you

use the twin secrets of acid dyeing: acidity

and heat. It doesn't take much acidity to

do the trick, the general rule is a glug of

vinegar per potful. That's right, a glug -

a scientific measurement of what happens when

you just tip the bottle. A small glug will

still work, perhaps not so well if you're

using very alkaline well water. A large glug

will work well if perhaps a bit too quickly,

and pure vinegar won't work any better. A

small point to remember here is that acidity

doesn't harm protein fibers, in fact slight

acidity is good for them. Remember how grandmas

used to rinse their hair with dilute vinegar

or lemon before commercial conditioners came

about?

Heat is another matter. The point is to bring

the fiber as close as you can

to boiling-water temperature, and to keep

it there a while -- about 15

minutes. If

you're using immersion dyeing, there's no

problem there, you just simmer the stuff,

and wait till the color is just what you want,

and/or till the water is clear. The trick

is to resist stirring if you're dyeing something

wooly. Remember that agitation in hot water

is a prime way to full wool... So you must

squash the urge to futz, or you'll have a

prettily colored hideous mess on your hands.

You might have to leave the room. You also

might consider that a roiling boil could cause

mild agitation. So you should try to keep

the water at Chinese tea making temperature

- steam rises off the top, but no actual bubbles

occur.

If you've painted

your fiber, you won't want to blur the results

irretrievably by dunking them in a lot of

water, what you need to do instead

is to steam. You can use the same Saran Wrap

that was protecting your counter to wrap the

fiber. You should probably seal the whole

thing into a Ziploc bag as well, if you painted

several colorways in one session and don't

want any potential mixing. Then into the usual

pot, with a couple inches of water at the

bottom and with an ordinary vegetable steamer

to hold the packages out of the water. The

length of time to steam is a more delicate

matter: larger bundles take longer for the

steam temperature to reach the inside. This

is just like cooking big Russet potatoes whole,

or cut up in pieces, you have to adjust the

cooking time according to the size of the

item, and to the general contents of the pot.

It's not unreasonable to steam a potful of

painted yarn an hour or so. And be sure not

to rinse till the whole thing is back to room

temperature, since more dye will be absorbed

in the cooling process.

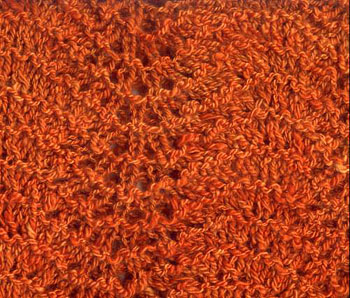

One

consequence of all this is that you can influence

how sharp your color delineation will be,

or how even vs heathered your solid colors.

Say you want to tone down a lovely cashmere

sweater in a tooth-stripping fluorescent color,

like I recently did. If you want an even color,

you'll soak the fiber thoroughly first, and

use a lot of water so that the dye gets to

all the fiber easily. You'll dunk it in almost

room-temperature water, and increase the heat

slowly. And finally you'll add the vinegar

slowly toward the end. If on the other hand

you want to get heathered yarn, or even have

some fabric come out almost tie-dyed, you'll

use all the opposite strategies. Be stingy

with the water so it's harder for the dye

to propagate. Dunk the fiber in already-simmering

water with a generous helping of vinegar,

maybe as much as a cup. Some of this also

applies to yarn painting: if you want a soft,

watercolor

One

consequence of all this is that you can influence

how sharp your color delineation will be,

or how even vs heathered your solid colors.

Say you want to tone down a lovely cashmere

sweater in a tooth-stripping fluorescent color,

like I recently did. If you want an even color,

you'll soak the fiber thoroughly first, and

use a lot of water so that the dye gets to

all the fiber easily. You'll dunk it in almost

room-temperature water, and increase the heat

slowly. And finally you'll add the vinegar

slowly toward the end. If on the other hand

you want to get heathered yarn, or even have

some fabric come out almost tie-dyed, you'll

use all the opposite strategies. Be stingy

with the water so it's harder for the dye

to propagate. Dunk the fiber in already-simmering

water with a generous helping of vinegar,

maybe as much as a cup. Some of this also

applies to yarn painting: if you want a soft,

watercolor

effect, let your fiber sit for 20 minutes

before you start steaming it,

giving the dyes a chance to diffuse and mix.

If you want clearly delineated colors, rush

them to the steam pot the instant you're done

painting.

Rinsing is part of the process, but doesn't

need to be done immediately, since nothing

will harm the fiber. A dash of Dawn will be

helpful in washing out every trace of unbound

dye. If you've measured your dye, you should

get pretty quickly to clear water. If not,

you may not have steamed/simmered your fiber

enough, and you might want to give it another

whirl in the pot, perhaps with a dash more

vinegar. In any case, keep in mind that wool

is still vulnerable to fulling even if you're

rinsing, so don't wring it about vigorously,

don't stream water right over it, just lay

it down gently on clean water to soak and

leave it alone a bit.

Pro-chem

sells Sabraset acid dyes, the best available.

Dharma

Trading merely calls them 'acid dyes'.

Great selection of stuff to dye on too.

Mendel's

sells Jacquard brand, best on silk but a fine

all-around acid dye, in smallish quantities.

Synthetic

Dyes for Natural Fibers

by Linda Knutson.

Interweave Press, 1986, out of print.

This is definitely THE textbook for synthetic

dyeing. Simple, straightforward, and extremely

thorough, you'll never need another.

Blue

and Yellow Don't Make Green

by Michael

Wilcox. School of Color Publishing, 2002.

An excellent text about how color really works

in different media, including color perception.

Introduces the concept of using different

primaries to get different color effects,

and shows color wheels for many combinations.

The

Twisted Sisters Sock Workbook: Dyeing, Painting,

Spinning, Designing, Knitting

by

Lynne Vogel. Interweave Press 2002

Fine for socks, but really great as a dyeing

text. Shows what can only be acquired by long

and painful experience otherwise, the relationship

between the look of a roving or yarn to how

it knits up.

Thanks to Judith McKenzie,

Sara Lamb and Nancy Finn for great workshops,

and to Nancy Roberts for the initial inspiration.