Feature: Our Knitting Roots: a study of the contributions immigrants have made to North American knitting, by Donna Druchunas

INTRODUCTION

Our Knitting Roots

by Donna Druchunas

It may be difficult to look at a sock or mitten that you've made with your own hands and feel a connection to a group of people who seem strange or foreign to you. But as knitters and as humans, we owe it to ourselves and to each other to forge these unlikely connections. Making things by hand, after all, is an intimate human endeavor and we should use it not only to knit strings into socks or sweaters or shawls, but also to knit person to person, strangers into friends.

In Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone, J.K. Rowling wrote, "There are some things you can't share without ending up liking each other, and knocking out a twelve-foot mountain troll is one of them."

Knitting is another.

Irish Stitches on Both Sides of the Pond

This year, I’ll be focusing my columns on knitting from the British Isles. In the past, I’ve avoided writing about knitting from this area of the world, because there is so much information available already. After all, who hasn’t heard of Fair-Isle colorwork, Shetland lace, or fisherman’s gansey sweaters? But I’ve decided to take a closer look at knitting from these islands to see what might be lurking beneath the surface. And for no reason in particular, I’ve decided to start with Ireland.

(Northern Ireland is officially part of the United Kingdom; however, for the purposes of this essay, I’m counting Northern Ireland as part of Ireland, because it’s on the same piece of land.)

When I think of Ireland, there are two types of handiwork that come to mind: Irish Lace Crochet and Aran Knitting.

My grandmothers were both talented crafters. Grandma Druchunas crocheted beautiful lace doilies as well as warm winter hats. She once gave me a crochet lace summer top that I wore until it disintegrated (which is just as well, because it would not fit me anymore). Irish lace crochet is “a kind of crocheted lace in which small motifs—crocheted leaves, flowers, and other shapes—are assembled into fabulous lace cloth or trimmings.”

My grandmothers were both talented crafters. Grandma Druchunas crocheted beautiful lace doilies as well as warm winter hats. She once gave me a crochet lace summer top that I wore until it disintegrated (which is just as well, because it would not fit me anymore). Irish lace crochet is “a kind of crocheted lace in which small motifs—crocheted leaves, flowers, and other shapes—are assembled into fabulous lace cloth or trimmings.”

Crochet was introduced to Ireland in the 1700s by Ursuline nuns from France. For over a hundred years, crocheted lace was only made in convents. But when the Irish Potato Famine came, many women began crocheting lace items at home to sell as a source of income. (Source: “The History of Irish Crochet Lace,” blog post from Interweave Press)

Grandma Tolen knit all kinds of pullovers and cardigans, including an entire collection of what she called “Irish patterns sweaters” in the 1970s, many of which have been passed down to me, my sister, and my cousins.

Grandma Tolen knit all kinds of pullovers and cardigans, including an entire collection of what she called “Irish patterns sweaters” in the 1970s, many of which have been passed down to me, my sister, and my cousins.

Today we call the dense cable patterns used in those Irish pattern sweaters “Aran Knitting.” These popular sweaters evolved from older style fisherman’s ganseys. In the in the 20th century they became the product we know today, and were made by local women as a way to add to their family’s income.

I wrote extensively about Aran Sweaters and included a pattern for an Aran cardigan in my column in the Winter 2012 issue of Knitty.

A Timeline of Knitting in Ireland

Most of the information that pops up on an Google search for “knitting in Ireland” is about Aran Knitting, but just like crochet, knitting was woven into the daily lives of women in Ireland long before the Aran sweater was invented. Legend holds that knitting was brought to Ireland in the year 1588, by sailors in the Spanish Armada when 24 ships were shipwrecked along the coast. There’s no evidence that this is true. But who knows? Knitting was known in Spain long before it came to the British Isles. While this story is fun, I find it much more interesting to look at documented facts about the history of knitting on the Emerald Isle:

- Before the technique of knitting came to Ireland, knitted products—stockings in particular—were imported from across the Irish Sea. “The first English produced knitted stockings to be exported abroad went to Ireland from Chester in the later 1570s, based on evidence from an account from 1577.” (Consumption and Culture in Sixteenth-Century Ireland: Saffron, Stockings and Silk, Irish Historical Monographs)

- A pair of hand-knit stockings in the National Museum of Ireland were made in the town of Carnamoyle in County Donnegal in the 16th century. The yarn used was handspun worsted singles. (“The Carnamoyle Stockings—Irish Wool Stockings from the 16th Century” by McGann Kass)

- Irish women began knitting their own stockings almost as soon as the imports from England started arriving. “A knitted wool stocking, associated with human remains, and dating from the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century was found in a bog in Derrindafferg in [County] Mayo. Also, in Waterford, excavations revealed fragments of good-quality knitting, which based on the shape appears to be part of a stocking leg, probably made of linen, which may have been either from hand or frame knitting, dating to the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century. This again suggests that new fashions stimulated a certain level of domestic production and that the Irish were importing new knitting techniques as well as the stockings themselves.” (Consumption and Material Culture in Sixteenth-Century Ireland by Susan Flavin)

- During the Stuart period (1603 to 1714), “The ladies of Ireland [were] generally elegant and frequently highly educated. Middle–class protestant women were often sent to various schools for specific instruction. For instance, girls were sent for a time to a sewing and again to a knitting school.” (“Tudor & Stuart Educational Policy” from the Ulster Historical Society)

- Because knitting was portable, women could knit while walking and while tending livestock in the fields. “Women stayed with the cattle and sheep over the summer as it was too far for calves to travel daily from the farm… They passed the time between milking by knitting or sewing.” (Connemara Infrastructure and Interpretation Plan, April 2012)

- “The women of Corofin and Ennistymon were scarcely ever seen 'without a stocking in her hand, which she continues to knit whilst walking a quick pace to the market; and even in the market-house, whilst selling or buying, her fingers are never idle.” (Statistical Survey of County Clare, 1808)

- Potato blight, a fungus that attacks potato and tomato plants, caused a severe famine in Ireland from 1845 to 1849, and “many Irish women and children turned to lacemaking to earn the money they needed to survive or emigrate.” (“Irish Crochet and the Great Potato Famine” by Katherine Durack)

- In the mid nineteenth century, knitting was required work for women and children in Irish workhouses. “The aged and infirm were expected to pick, card and spin wool, knit and mend or make clothes for the inmates, and in 1847 the union inspector, Samuel Horsley, suggested that the infirm should be employed in making stockings for the house.” (source: Visiting Committee Report Book, December 1847)

- Just before the turn of the century, Arthur Balfour, a politician who would later become Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, “paid a visit to Pattison’s knitting depot which provided work for women in the district” and wrote that “[T]he knitwear industry at Glenties... now ‘employs half the countryside’.” (Source: “Arthur Balfour’s Tour of Donegal, 1890” in the Donegal Annual, No. 57, 2005)

- In the twentieth century, hand knitting was still an important source of income for women in county Donnegal, just around the same time that cabled Aran Sweater was developed into a commercial product on the Aran Islands. “At East Wall, in Derry, again, are the headquarters of the Donegal knitted woolens, which are such a blessing to the peasantry… Here the knitted golf coats for women were originated, which have become so fashionable within the last few years that the market is now flooded with cheap Continental imitations. Made in the cottages, but collected here at East Wall, are also the well-known knitted gloves for both men and women; and if the reader will notice the black winter gloves worn by the London Police Force, he will see a good sample of the Donegal-Derry glove.” (The Ireland of Today: With Illustrations, by Small Maynard, 1915)

There is doubtless much more information available in local museums and in people’s heads in Ireland. And knitting traditions have continued to be passed on and to evolve into new styles and techniques right up to the present day.

Appreciate the Craft, appreciate the Crafters

I started this column to share the idea that to appreciate knitting is to appreciate the contributions of immigrants and of the people and cultures who originated the techniques and patterns that we love. Because I live in America and my family is relatively new here, the bulk of my knowledge is about immigrant life in the United States. During the 1845 to 1849 Potato Famine—about half century before my family left the “old country,” and well over a half century before Aran Knitting would be invented—about a million and a half Irish children, women, and men left Ireland to look for a better life in the USA. Of course, Irish women and girls (and likely some men and boys as well) brought their knitting needles and crochet hooks as well as their skills at making stitches, garments, and accessories. But just as with my family, these impoverished immigrants often didn’t find the streets of gold they were looking for.

“The emigrants who land at New York, whether they remain in that city or come on in the interior, are not merely ignorant and poor—which might be their misfortune rather than their fault—but they are drunken, dirty, indolent, and riotous, so as to be the objects of dislike and fear to all in whose neighbourhood they congregate in large numbers.”

“[T]hey steal, they are cruel and bloody, full of revenge, and delighting in deadly execution, licentious, swearers and blasphemers, common ravishers of women, and murderers of children.”

Do these quotes sound like they came from last week’s news? Can you guess who said these things and about whom? Both quotes are about Irish Immigrants coming to America in the 19th century. The first quote is from The Eastern and Western States of America written by James Silk Buckingham in 1842 and the second is from The Works of Edmund Spenser written in 1849.

Because there was so much prejudice against Irish immigrants in the nineteenth century, few jobs were open to them. In fact, newspapers and help wanted posters often contained the note “NO IRISH NEED APPLY.” Most Irish woman ended up working as servants and domestic workers, and many men worked building canals and railroads, or in coal mines, as my Lithuanian great-grandfather did.

For the past month or so, many in the knitting community have become aware of racism in our little corner of the world. If you’re on Instagram or Facebook, you’ve undoubtedly seen posts on this topic. We can learn a lot by looking at the history of the Irish in America and by thinking about what lessons we can take from their history to use in recognizing and dismantling white supremacy today. Rather than speaking in my own words on this topic, to close this article, I’d like to share a few quotes from the book My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies by Resmaa Menakem.

“At various periods in America’s history, immigrants from Germany, Ireland, and Italy, as well as Jews from Eastern Europe, were considered non-white. I don’t just mean they were looked down upon and mistreated, though they surely were. They were also formally and officially designated as non-white by American laws, regulations, and policies, as well as in the American press. Phrases like ”the Irish race” and “the Jewish race” were widely used and accepted.”

“Within a generation or two, however, each these new white immigrant groups was socialized, colonized, and accepted by other Americans by being inducted in the false community of whiteness. One group (and one generation) of poor white people after another began to see their interests aligned with the ruling class... white folks were told, ‘Whether we’re rich or poor, we’re all white, so there is no need for us to fight each other. Instead, we need to band together to fight the villains among us: Black [people]’.”

So what does this all mean for today, and what can we do? Menakem suggests that those of us who have immigrant ancestors who were oppressed have a powerful opportunity to use our own family histories to fight racism. Many ethnic and religious groups in the USA have community centers, heritage institutes, and cultural schools. Menakem mentions the German-American Institute and the Ukrainian American Community Center, in his home town. I think of Hebrew school and Greek school that many of my friends attended as children, as well as the Vermont Folklife Center in my current home state.

Menakem concludes that, “You might encourage your organization to make the dismantling of white-body supremacy part of its mission. May religious organizations, and many service organizations from non-European nations and their descendants, are already doing similar things. It would not take a great deal of effort for European-focused service organizations to follow their lead.”

As knitters, many of us participate in guilds and informal knitting groups. Make sure you reach out to knitters of color in your community and invite them to participate and ask them to be leaders in your group. For guilds, being a leader might mean joining the board, speaking at meetings, or teaching workshops. For each informal group, what “being a leader” looks like will be different. Perhaps you can start by having your group create a statement like this, based on the one Menakem recommends for cultural centers. (If you live in a country other than the USA, you can modify the text to fit your specific needs.)

“When the creators of our favorite knitting traditions and inspirations came to America, many were looked down upon and denied opportunities because of where they came from. Eventually some were accepted as full citizens and normal human beings—but at the cost of diluting their heritage and becoming ”white” people. We reject that identity. We are not content to passively accept the identity and perks of whiteness. We are proud to be American knitters and we acknowledge, honor, and respect the people and cultures who created the textiles, traditions, patterns, and techniques that we enjoy and are inspired by. We stand together with Native Americans, African Americans, and the descendants of immigrants from every nation, against the constraints and dehumanization of white-body supremacy.”

(That’s it for serious topics for a while. In my next columns we’ll explore the history of sock knitting in Wales, Beatrix Potter’s experience raising sheep in England, and the knitting fashions of Outlander in Scotland.)

Cailleach Beara, a free knitting pattern from Knitty.com. Free knitting pattern for a short-sleeved lacy pullover.

INTRODUCTION

Cailleach Beara

by Donna Druchunas

by Donna Druchunas

![]()

This sweater is inspired by the crochet summer top Grandma Druchunas gave me and a lace twinset Grandma Tolen made in the 1970s. Although it's not traditional Irish Lace, because it’s not crocheted, I made this sweater to remember the crochet lace that I wore years ago.

Made from the top down in one piece, there is no complex shaping of the lace pattern. The increases for the raglan shaping of the yoke and the A-line shaping of the body are worked into stockinette stitch, copying the way my grandmother knit lace sweaters. This eliminates the need to fiddle with changing stitch counts in the lace patterning and adds a distinct and appealing design element to the garment. When I wore this for taking photos, I knew right away that this would be a summer sweater, just like the one I had as as a child, that I would wear until it disintegrates. I hope you love it as much as I do.

model: Donna Druchunas

model: Donna Druchunas

photos: Dominic Cotignola

photos: Dominic Cotignola

SIZE

Women's XS[S, M, L, 1X, 2X, 3X]

shown in size 1X with 5 inches / 12.5 cm of ease

FINISHED MEASUREMENTS

Bust circumference: 34.5[38, 41.75, 46, 50.5, 54.25, 58.5] inches/ 87.5[96.5, 106, 117, 128.5, 138, 148.5] cm

Length: 22.75[23, 23.5, 24, 24.25, 25.25, 26] inches / 58[58.5, 59.5, 61, 61.5, 64, 66] cm

MATERIALS

![]() Valley Yarns Granville, (90% Pima Cotton/10% Merino Wool, 167yd/153m per 50g ball); color: Coral (12); 5[6, 7, 7, 8, 9, 10] balls

Valley Yarns Granville, (90% Pima Cotton/10% Merino Wool, 167yd/153m per 50g ball); color: Coral (12); 5[6, 7, 7, 8, 9, 10] balls

Recommended needle size

[always use a needle size that gives you the gauge listed below - every knitter's gauge is unique]

![]() US #4/3.5mm needles for working in the round: 24"/60cm and 16"/40cm long circulars or 1 long circular for magic loop or 2 circulars

US #4/3.5mm needles for working in the round: 24"/60cm and 16"/40cm long circulars or 1 long circular for magic loop or 2 circulars

![]() US #3/3.25mm needles for working in the round: 24"/60cm and 16"/40cm long circulars or 1 long circular for magic loop or 2 circulars

US #3/3.25mm needles for working in the round: 24"/60cm and 16"/40cm long circulars or 1 long circular for magic loop or 2 circulars

Notions

![]() stitch markers including 4 removable markers

stitch markers including 4 removable markers

![]() scrap yarn or 2 spare cables

scrap yarn or 2 spare cables

![]() tapestry needle

tapestry needle

GAUGE

23 sts and 30 rnds = 4 inches /10 cm over Stockinette Stitch with larger needles

PATTERN NOTES

[Knitty's list of standard abbreviations and techniques can be found here.]

Sweater is worked from the top down, in the round. Back and Front are identical.

Seed Stitch (worked over an even number of sts)

Rnds 1: (K1, p1) around.

Rnd 2: (P1, k1) around.

Rep Rnds 1-2 for patt.

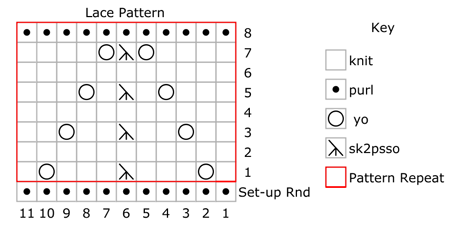

Lace Pattern (worked over multiple of 11 sts)

Lace Pattern (worked over multiple of 11 sts)

Note: 11 more sts on each side are brought into Lace Pattern repeat on Rnd 32.

Markers are moved to each side of new sts.

Continue to work Lace Pattern over all sts between both markers on following rnds.

Set-up rnd: Purl.

Rnd 1: *K1, yo, k3, sk2po, k3, yo, k1; rep from * to end.

Rnds 2, 4, and 6: Knit.

Rnd 3: *K2, yo, k2, sk2po, k2, yo, k2; rep from * to end.

Rnd 5: *K3, yo, k1, sk2po, k1, yo, k3; rep from * to end.

Rnd 7: *K4, yo, sk2po, yo, k4; rep from * to end.

Rnd 8: Purl.

Rnds 9-31: Rep Rnds 1-8 two times more, then work Rnds 1-7 once.

Rnd 32: Patt to 12 sts before Lace Pattern marker, p1, pm, (purl to m, remove m) twice, p11, pm, p1, patt to end.

For Front/Back Lace Pattern section only: Rep Rnds 1-32 1[1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 3] times more, then rep Rnds 1-8 over these 77[77, 88, 110, 121, 132, 154] sts for remainder of pattern.

For Sleeve Lace Pattern section only: Rep Rnds 1-32 0[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1] time, then rep Rnds 1-8 over these 44[44, 44, 44, 44, 66, 88] sts for remainder of pattern.

DIRECTIONS

YOKE

With smaller needles, CO 110[114, 120, 124, 130, 136, 136] sts. Join to work in the round, being careful not to twist sts, and pm for beg of rnd.

Work 4 rnds in Seed st.

Next rnd: K 12[18, 2, 4, 10, 9, 1] , m1, (k 2[2, 3, 3, 2, 2, 2] , m1) to last 12[18, 1, 3, 10, 9, 1] st(s), k to end. 154[154, 160, 164, 186, 196, 204] sts.

Change to larger needles and place removable markers for raglan in round as follows (first raglan marker already in place at beg of rnd/right front raglan): second raglan marker after first 53[53, 56, 58, 69, 74, 78] sts (for Front), next raglan marker after 24 sts (for Left Sleeve), next raglan marker after next 53[53, 56, 58, 69, 74, 78] sts (for Back). Rem 24 sts of round are for Right Sleeve.

Next rnd: *K2, yo, k 7[7, 3, 4, 4, 1, 3] , p1, pm, work next 33[33, 44, 44, 55, 66, 66] sts in Set-up Row of Lace Pattern, pm, p1, k 7[7, 3, 4, 4, 1, 3] , yo, k2, sl m, k2, yo, k20, yo, k2; rep from * once more. 162[162, 168, 172, 194, 204, 212] sts: 55[55, 58, 60, 71, 76, 80] sts for Front/Back, 26 sts for each Sleeve.

Even rnd: *Sl m, knit to 1 st before m, p1, sl m, work next row of Lace Pattern to m, sl m, p1, knit to m, sl m, knit to next m; rep from * once more.

Raglan inc rnd 1: *Sl m, k2, yo, knit to 1 st before m, p1, sl m, work next row of Lace Pattern to m, sl m, p1, knit to 2 sts before m, yo, k2, sl m, k2, yo, knit to 2 sts before m, yo, k2; rep from * once more. 8 sts increased.

Rep last 2 rnds 14 times more, then work Even rnd once, ending after Rnd 31 of Lace Pattern. 282[282, 288, 292, 314, 324, 332] sts: 85[85, 88, 90, 101, 106, 110] sts for Front/Back, 56 sts for each Sleeve.

Next rnd: *Sl m, k2, yo, patt (working Rnd 32 of Lace Pattern) to 2 sts before next raglan m, yo, k2, sl m, k2, yo, k3, p1, pm, p44, pm, p1, k3, yo, k2; rep from * once more. 290[290, 296, 300, 322, 332, 340] sts: 87[87, 90, 92, 103, 108, 112] sts for Front/Back, 58 sts for each Sleeve.

Note: One pattern repeat has now been added to each side of Lace Pattern on Front and Back. 44 sts in center of each Sleeve will also now also be worked in Lace Pattern. The next rnd of Lace Pattern will be Rnd 1. Continue to work 1 st on each side of Lace Pattern in purl.

Work 1 rnd even in patt.

Raglan inc rnd: *Sl m, k2, yo, patt to 2 sts before raglan m, yo, k2; rep from * three times more. 8 sts increased.

Rep last 2 rnds 2[6, 10, 13, 15, 18, 21] times more. 314[346, 384, 412, 450, 484, 516] sts: 93[101, 112, 120, 135, 146, 156] sts each for Front/Back; 64[72, 80, 86, 90, 96, 102] sts for each sleeve.

Work even in patt until piece measures 7.25[7.75, 8.25, 8.75, 9.25, 10.25, 11] inches / 18.5[19.5, 21, 22, 23.5, 26, 28] cm from cast-on.

Divide for Body and Sleeves:

Next rnd: *Patt to next raglan m, remove m, slip next 64[72, 80, 86, 90, 96, 102] sleeve sts to holder, remove m, CO 3[4, 4, 6, 5, 5, 6] sts, pm for side “seam,” CO 3[4, 4, 6, 5, 5, 6] sts; rep from * once more. Join once more to work in the round. 2 side seam markers now in place. 198[218, 240, 264, 290, 312, 336] sts: 99[109, 120, 132, 145, 156, 168] sts each for Front/Back.

Body

Next rnd: Patt to 3 sts before side seam marker, work next 6 sts in Seed st, patt to 3 sts before next side seam marker, patt 3 sts in Seed st. This marker is the new beg of rnd.

Rnd 1: *Work 3 sts in Seed stitch, pm, work in patt as est to 3 sts before side seam marker, pm, work 3 sts in Seed stitch; rep from * once more.

This sets the patt of Lace Patt in center of Front and Back and sts either side of side markers in Seed st.

Work 7[7, 7, 11, 11, 11, 11] rnds even in patt.

Side inc rnd: *Sl m, work seed st to m, M1, sl m, (patt to m, sl m) 3 times, M1, work seed st to side seam m; rep from * once more. 4 sts increased.

Rep last 8[8, 8, 12, 12, 12, ] rnds 9[9, 9, 6, 6, 6, 6] times more, working increases into Seed st patt. 238[258, 280, 292, 318, 340, 364] sts.

Work even in patt until work measures 12.5[12.25, 12.25, 12.25, 12, 12, 12] inches / 32[31, 31, 31, 30.5, 30.5, 30.5] cm from underarm or 1 inch / 2.5 cm shorter than desired length, ending after rnd 8 of Lace Pattern and removing all but beg of rnd marker on last rnd.

Change to smaller needles and work in Seed Stitch around for 1 inch / 2.5 cm.

BO loosely in Seed st.

Sleeves

Join yarn at centre of underarm and pick up and knit 3[4, 4, 6, 5, 5, 6] sts to held sts, work across 64[72, 80, 86, 90, 96, 102] held Sleeve sts in patt, pick up and knit 3[4, 4, 6, 5, 5, 6] sts to center of underarm. Pm for beg of rnd and join to work in the rnd. 70[80, 88, 98, 100, 106, 114] sts.

Rnd 1: Work 3 sts in Seed st, work in est patt to last 3 sts, work 3 sts in Seed st.

Work even in patt as est for approx. 3[3.5, 3, 3.5, 3, 3.25, 3.5] inches / 7.5[9, 7.5, 9, 7.5, 8.5, 9] cm or until sleeve measures 1 inch / 2.5 cm shorter than total desired length, ending after Rnd 8 of Lace Patt and removing all but beg of rnd marker on last rnd.

Change to smaller needles and work in Seed st for 1 inch / 2.5 cm.

BO loosely in Seed st.

Repeat for other sleeve.

FINISHING

Weave in ends. Wash and dry flat, blocking to measurements.

Note: Lace can be stretched quite aggressively when blocking. Make sure you measure and pin the sweater to dimensions.

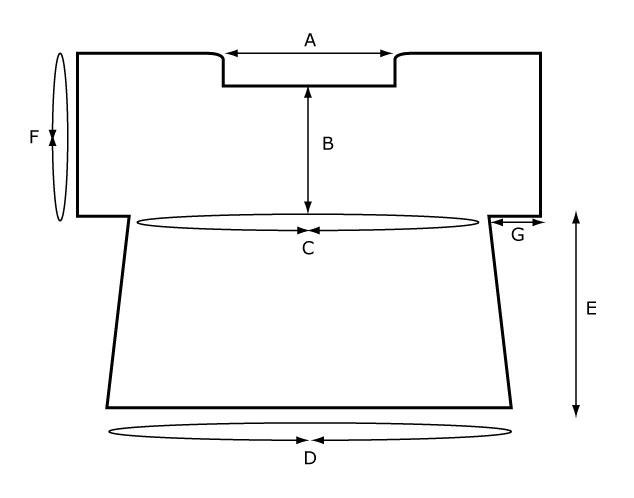

A: Back neck width (stretched): 9.25[9.25, 9.75, 10, 12, 12.75, 13.5] inches / 23.5[23.5, 25, 25.5, 30.5, 32.5, 34.5] cm

B: Raglan length: 7.25[7.75, 8.25, 8.75, 9.25, 10.25, 11] inches / 18.5[19.5, 21, 22, 23.5, 26, 28] cm

C: Bust circumference: 34.5[38, 41.75, 46, 50.5, 54.25, 58.5] inches / 87.5[96.5, 106, 117, 128.5, 138, 148.5] cm

D: Hem circumference: 41.5[44.75, 48.75, 50.75, 55.25, 59.25, 63.25] inches / 105.5[113.5, 124, 129, 140.5, 150.5, 160.5] cm

E: Body length: 13.5[13.25, 13.25, 13.25, 13, 13, 13] inches / 34.5[33.5, 33.5, 33.5, 33, 33, 33] cm

F: Upper arm circumference: 12.25[14, 15.25, 17, 17.5, 18.5, 19.75] inches / 31[35.5, 38.5, 43, 44.5, 47, 50] cm

G: Sleeve length: 3[3.5, 3, 3.5, 3, 3.25, 3.5] inches / 7.5[9, 7.5, 9, 7.5, 8.5, 9] cm

ABOUT THE DESIGNER

Donna Druchunas is obsessed with her family history and the history of knitting. In combination with this column, Our Knitting Roots, she is also running a book club for knitters who appreciate the people, places, and cultures behind the stitches of their knitting projects.

Donna Druchunas is obsessed with her family history and the history of knitting. In combination with this column, Our Knitting Roots, she is also running a book club for knitters who appreciate the people, places, and cultures behind the stitches of their knitting projects.

Donna’s newest project is opening a small local yarn shop in rural Vermont. Visit her online store to order kits for her Knitty projects as well as other yarns, books, and notions. She is the author of many knitting books including her newest title: The Art of Lithuanian Knitting. Donna has taught knitting workshops in the United States, Canada, and Europe and she holds annual retreats in Vermont.

You'll also find her on Ravelry.

Pattern & images © 2019 Donna Druchunas.