Feature: Our Knitting Roots: a study of the contributions immigrants have made to North American knitting, by Donna Druchunas

INTRODUCTION

Our Knitting Roots

by Donna Druchunas

It may be difficult to look at a sock or mitten that you've made with your own hands and feel a connection to a group of people who seem strange or foreign to you. But as knitters and as humans, we owe it to ourselves and to each other to forge these unlikely connections. Making things by hand, after all, is an intimate human endeavor and we should use it not only to knit strings into socks or sweaters or shawls, but also to knit person to person, strangers into friends.

In Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone, J.K. Rowling wrote, "There are some things you can't share without ending up liking each other, and knocking out a twelve-foot mountain troll is one of them."

Knitting is another.

This issue: Jamaica: Where Lace Once Grew on Trees

When author Steeve Buckridge looks at a delicate piece of lace, he immediately thinks of his mother and grandmother who passed down their knowledge of needlework and Jamaican herbalism to him from previous generations of women. He envisions their hands knitting, sewing, planting, and harvesting. He dreams of his ancestors, enslaved and free African women, bringing traditions of cloth making with them across the Atlantic ocean to the Caribbean. Using natural resources and their own ingenuity, they created fashionable clothing that spoke of their power, autonomy, and beauty in a world that considered them to be unworthy.

Elusive Knitting Traditions

When I write about our knitting roots, or the historical traditions of knitting around the world, I usually focus on a knitting technique, type of stitch pattern, or garment that was made as folk art in a particular place and time. My own designs are most often modeled on vintage pieces I’ve seen in museums, books, or private collections during my travels. Over the years I’ve written about garments and accessories such as elaborate lace shawls in Estonia, intricate toe-up socks in Albania, brightly colored chullo caps in Peru, and delicate pattern stitches from Japan.

There are other places I’ve wanted to learn about, too. Places where I could not find any information about knitting in the past. It’s easy to find out about knitting in Northern Europe, Russia, North and South America, and even Southern Europe and the Middle East. But there are many places where signs of knitting have not been apparent to me. Perhaps it’s because nothing has been published in English or perhaps it’s because knitting wasn’t a popular, traditional craft in those areas. Maybe knitting isn’t very useful in areas without cold winters. Or people didn’t knit because wool and cotton weren’t readily available and they had other ways to create the clothing they needed. Even after searching and poking around, I’m left with questions about knitting from places across the world from where I live: Is knitting popular in any African nations? What about Southeast Asia? Has knitting been fashionable in Malaysia or Thailand? I have questions about knitting in places close to home, too: Are there historical knitting traditions in Cuba or Haiti? What about Puerto Rico or Jamaica? What comes to mind for me when thinking of the Caribbean is the brightly-colored knit and crochet caps made by Rastafarians. But what older knitting traditions may have existed in the past? With a lack of information about knitting, specifically, I find myself looking into other textile traditions of the region.

There are other places I’ve wanted to learn about, too. Places where I could not find any information about knitting in the past. It’s easy to find out about knitting in Northern Europe, Russia, North and South America, and even Southern Europe and the Middle East. But there are many places where signs of knitting have not been apparent to me. Perhaps it’s because nothing has been published in English or perhaps it’s because knitting wasn’t a popular, traditional craft in those areas. Maybe knitting isn’t very useful in areas without cold winters. Or people didn’t knit because wool and cotton weren’t readily available and they had other ways to create the clothing they needed. Even after searching and poking around, I’m left with questions about knitting from places across the world from where I live: Is knitting popular in any African nations? What about Southeast Asia? Has knitting been fashionable in Malaysia or Thailand? I have questions about knitting in places close to home, too: Are there historical knitting traditions in Cuba or Haiti? What about Puerto Rico or Jamaica? What comes to mind for me when thinking of the Caribbean is the brightly-colored knit and crochet caps made by Rastafarians. But what older knitting traditions may have existed in the past? With a lack of information about knitting, specifically, I find myself looking into other textile traditions of the region.

The Caribbean was in the news a lot over the past year as the islands were devastated by Hurricanes Irma and Maria. So when I stumbled on to the book African Lace-Bark in the Caribbean by Steeve Buckridge, it immediately caught my attention. The cover features a photograph of a fine lace fabric with a pattern of diamonds that could be made by weaving, netting, or sprang. Inside the pages are references to and photos of delicate lacy shawls, doilies, caps, and dresses. None of these were made out of man-made fabric. The lace used to create these fashions literally grew on trees.

Natural Lace

The fabric known as “lace-bark” was made out of an inner layer of bark from a tree native to the islands of Jamaica, Cuba, and Hispaniola. Historically known by many common names including the “lace stick,” “white bark,” “Indian lace,” and “gauze” tree, the scientific name of the lace-bark tree is Lagetta lagetto. The sheer fabric made by soaking, stretching, and sun-bleaching the bark is so delicate that it is often confused with hand-made lace or gauze.

Lagetta lagetto bark. Photo courtesy of Alan Franck, University of South Florida Herbarium.

How was this “natural lace” discovered and why was it used? And who wore the garments and accessories made from it? This is what Steeve Buckridge unearths in African Lace-Bark in the Caribbean.

It’s unclear if the pre-colonial inhabitants of Jamaica and Haiti used the bark of the lagetto tree to make lace, but they did use it to make “ropes, hammocks, and baskets.” West-African slaves brought to the Caribbean would have had experience making other kinds of cloth from the bark of trees. By combining their knowledge, it’s likely that Jamaican and African women worked together to create natural lace when they could not afford or were not allowed to purchase hand-made or manufactured lace imported by white colonists.

Dressing to Resist

Slave owners were only required to provide a modicum of clothing or fabric to their slaves—about enough to make two coarse linen “frocks” and one woolen “great coat.” Men received more rations than women, who were expected to make any additional clothing they needed for themselves, to purchase clothes with the small income they might make from selling produce from their own gardens, or to exchange sex for extra garments.

Although many historical documents deal with stories of men as leaders of anti-slavery resistance, women resisted in their own ways. Passing down the traditions of their original cultures was one way that enslaved and free African women in the Caribbean might use clothing as a means to resist oppression. Making and wearing lace-bark was another.

In an interview with ARC Magazine, Buckridge explains: “During slavery in Jamaica... slaves had much control over their clothing, but the way one dressed within the colonial state was constantly scrutinized. As a result, enslaved people used their dress...to symbolically and covertly resist, to make satirical and politically subversive or revolutionary statements against the oppressor or colonial power... Furthermore, dress and the body became objects for deliberate manipulation, in an effort to change the power dynamics.”

There is something quite subversive about enslaved women making beautiful clothing out of lace-bark when plantation owners used the same material to construct whips.

Victorian Lace

When slavery was abolished in the British Empire in 1833, the role of lace-bark changed along with so much else in society. In Victorian times, “natural lace” was used to create kitschy souvenirs more than practical clothing and accessories.

Buckridge explains in an article “The Amazing Lace-bark Tree of Jamaica”: “Many freed black women chose not to wear lace-bark because it was associated with slavery. Others were lured and seduced by the abundance of imported fabrics that was once denied to them and the ease with which these items could now be purchased. Some embraced European imported fabrics as a means of elevating their status in the new social order.”

A selection of early 20th century Jamaican souvenir items including a woman's shawl (left), a fan (center), and several doilies, all made of lacebark with other materials. From Alfred Leader's 1907 account Through Jamaica with a Kodak.

Lace Bark Today

Today the lace-bark tree is rare and few people remember how to make the once renowned lace from its bark. But we can carry on memories of lost traditions and fibers in our own knitting work and in the stories we share.

There are many immigrants in the United States who have come from Jamaica, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic where the bark of the lagetto tree was once used to make lace. All of these people bring with them stories, customs, and traditions of their families and cultures. African Lace-Bark in the Caribbean: The Construction of Race, Class, and Gender by Steeve Buckridge provides a fascinating look at one such tradition from Jamaica.

My ancestors came from Lithuania, where knitting is one of the newest fiber crafts. Traditional knitted designs and garments adapted motifs that were originally used in weaving, sprang, pottery, and metal work. Perhaps your ancestors come from Africa, the Caribbean, or some other area where there were not traditions of knitting clothing or accessories. You can still adapt their work, motifs, ideas, and stories to inform your own knitting today and to pass on their dreams and traditions to future generations.

Further Reading

- African Lace-Bark in the Caribbean: The Construction of Race, Class, and Gender by Steeve Buckridge tells the story that I’ve barely outlined in this column. The author’s article, “The Amazing Lace-bark Tree of Jamaica,” in Voices 2017 is an overview.

- The knitting books Victorian Lace Today by Jane Sowerby and Knitting Lace: A Workshop with Patterns and Projects by Susanna Lewis are invaluable resources for learning more about Victorian knitting stitches and patterns.

- Wrapped in Comfort: Knitted Lace Shawls by Alison Hyde contains more information and a collection of patterns for circular lace shawls that are knit back and forth in the same style as my Lagetta lagetto shawl.

INTRODUCTION

Lagetta Lagetto

![]()

Just as the Lace Bark of Jamaica incorporates traditions and styles from many different sources, so does my shawl. The pattern itself is inspired by the Lace Bark garments and accessories made by African women in Jamaica in the 17th and 18th centuries. The pattern stitches are from the Victorian era, and represent the changes in fashion in Jamaica, and the Lace Bark doilies and souvenirs created for the tourist industry after the slaves gained their freedom. The shape of the shawl was invented by Alison Hyde in her book Wrapped in Comfort: Knitted Lace Shawls.

This pattern is dedicated to the women of Jamaica, past, present, and future, who pass down their traditions through words, actions, and stitches.

model: Donna Druchunas

model: Donna Druchunas

photos: Dominic Cotignola

photos: Dominic Cotignola

SIZE

One

FINISHED MEASUREMENTS

Depth: 21 inch/53.5cm, blocked

MATERIALS

Yarn

![]() ModeKnit Yarns ModeWerk Fingering [80% merino/20% nylon; approx 400 yd per 100g skein]; 2 skeins in color 008 Platinum

ModeKnit Yarns ModeWerk Fingering [80% merino/20% nylon; approx 400 yd per 100g skein]; 2 skeins in color 008 Platinum

Recommended needle size

[always use a needle size that gives you the gauge listed below - every knitter's gauge is unique]

![]() US#7/4.5mm circular needle at least 24 inches/60cm long

US#7/4.5mm circular needle at least 24 inches/60cm long

Notions

![]() yarn needle

yarn needle

![]() stitch markers

stitch markers

GAUGE

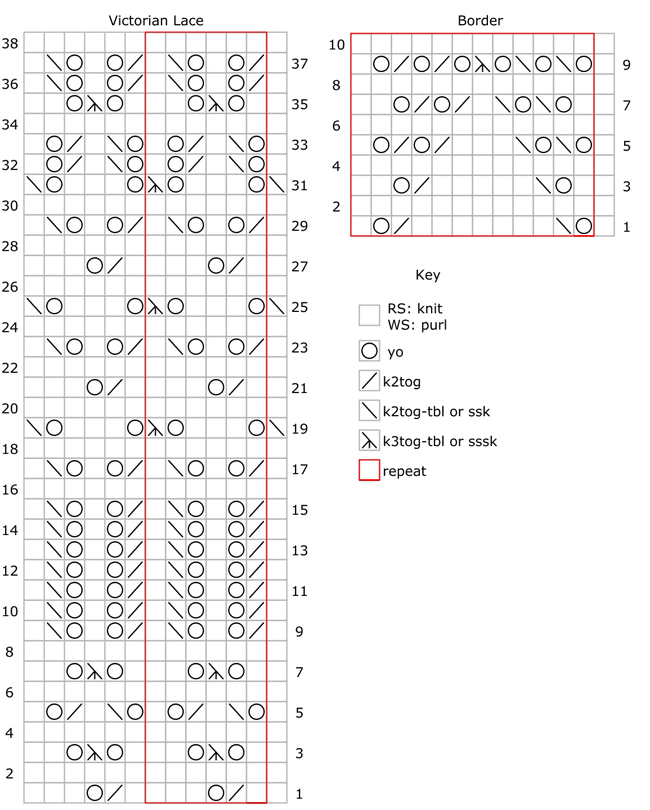

18 sts/24 rows = 4 inches/10 cm over rows 17-38 of Victorian Lace pattern on body using US#7/4.5mm needles, blocked

Note: Because of the shape of this shawl, the lace pattern will open up more on the yoke than it does in the body, and the gauge will be different closer to the increase rows, so the gauge of Victorian Lace chart rows 1-13 will be different in each section after it is blocked. Gauge isn't crucial for this pattern, as long as you like the fabric that results. Working at a different gauge will change yarn usage, and will result in a different size piece.

PATTERN NOTES

[Knitty's list of standard abbreviations and techniques can be found here.]

Double-Stranded Wide Cast On <—video link

Use a long-tail cast on with a double strand of yarn. As you cast on each stitch, push it back about 1 inch/2.5cm from the tip of the needle and hold it there while you cast on the next stitch. This creates a very loose and wide cast-on edge, that makes the neck edge both soft and strong. Cut the extra strand after completing the cast on, leaving a tail at least 12 inches/30cm long. Weave in the ends as you work the first row.

CHARTS

Note: Last 6 sts of Victorian Lace chart are the same as repeat except on rows 19, 25, and 31.

DIRECTIONS

With a double strand of yarn and the double-stranded wide cast on technique, CO 13 sts.

Neck

Row 1 (and all following odd-numbered rows) [WS]: Purl.

Row 2 [RS]: (K1, yo) to last st, k1. 25 sts.

Row 4: (K1, yo) to last st, k1. 49 sts.

Row 6: (K1, yo) to last st, k1. 97 sts.

Row 7 [WS]: Purl.

Yoke

Row 1 [RS]: Beg with Victorian Lace chart row 1, work first st of chart, then work 6 st rep 15 times across, then work last 6 sts once.

Rows 2-13: Continue working chart patt as set.

Row 14 [WS]: Purl.

Row 15, increase [RS]: (K1, yo) across, to last st, k1. 193 sts.

Row 16: Purl.

Row 17: Beg with Victorian Lace chart row 1, work first st of chart, then work 6 st rep 31 times across, then work last 6 sts once.

Rep Rows 2-16 once more. 385 sts.

Body

Row 1 [RS]: Beg with Victorian Lace chart row 1, work first st of chart, then work 6 st rep 64 times across.

Work rows 2-30 of chart once, then work rows 31-38 twice.

Border

Row 1 [RS]: Beg with Border chart row 1, work first st of chart, then work 12 st rep 32 times across.

Work rows 2-10 of chart once.

BO loosely on RS as follows:

K1, *k1, insert left ndl into 2 sts on right ndl and k2tog-tbl; rep from * until all sts are bound off. Cut yarn. Draw tail through rem loop to fasten off.

FINISHING

Wash, pin out to curved shape placing one pin in each cast on stitch at the neck stitch, one pin in every other row down side edges, and one pin in each point on the bind off edge.

Allow to dry thoroughly before unpinning.

ABOUT THE DESIGNER

Donna Druchunas is obsessed with her family history and the history of knitting. In addition to writing this column about Our Knitting Roots, she is also running a book club for knitters who want learn to appreciate the people, places, and cultures behind the stitches of their knitting projects. She is the author of many knitting books including her newest titles: How to Knit Socks that Fit and The Art of Lithuanian Knitting . Donna has taught knitting workshops in the United States, Canada, and Europe and she has five knitting classes on Craftsy.

Donna Druchunas is obsessed with her family history and the history of knitting. In addition to writing this column about Our Knitting Roots, she is also running a book club for knitters who want learn to appreciate the people, places, and cultures behind the stitches of their knitting projects. She is the author of many knitting books including her newest titles: How to Knit Socks that Fit and The Art of Lithuanian Knitting . Donna has taught knitting workshops in the United States, Canada, and Europe and she has five knitting classes on Craftsy.

Her newest project is opening a small local yarn shop in rural Vermont where lives she with her husband, mother, three cats and a long-haired Chihuahua. Visit Donna's website.

Pattern & images © 2018 Donna Druchunas