|

|

|

|

Listen, I’m as fond of a truly epic knitting project as the next lumberjack. But after cranking out the doll’s costume from the last two issues–with its four feet of lace edging and twenty-seven successively larger petticoats (the outermost doubles as a cow cozy)–when Knitty said, “For the Winter issue, how about a scarf?”, I said, “Oh, mais oui!” Because, frankly, Daddy needed a break. Scarf knitting, except perhaps of the Doctor Who variety, is not generally held to be epic. Scarves are for newbies. Scarves are what you knit when you can’t knit anything else, or when you really need a scarf. A scarf is a breeze, a bore, a washcloth that doesn’t know when to quit. Right. So I started rummaging through the books. Plenty of scarves to choose from. Here a scarf, there a scarf. Some, of course, so simple as to barely count as patterns. (Cast on, knit moss stitch until you’ve had enough, bind off. You’re welcome.) Others…intriguing. Lace? In multiple colors? In intarsia? Don’t mind if I do. Except upon closer inspection, the most interesting scarves also required that I “knit until center measures approximately four yards. Then…” Then? I’m sorry, no. Maybe some other time, but not right now. Not on a deadline. Not with the holidays almost at my throat. After you’ve cajoled me into knitting four wide yards of lace, you’d better not follow it with “then” unless what follows “then” is “let me finish that for you, while you go get a massage.” I was on the verge of sending Knitty a counteroffer (“How about a penwiper?”) when I ran across Jane Gaugain’s “Faucett, or Bandeau for Neck.” Right there in the preamble, the eminently sensible Mrs. Gaugain gives the dimensions for the completed project: three inches wide, three-quarters of a yard long. Wrap it up, I’ll take it. So I jumped into this assuming “Well, it’s for the neck. It must be a scarf.” But it was impossible to be sure. The more I knit, the less sure I became. Three-quarters of a yard sounds long, or at least long-ish, until you wrap it around your neck and realize how long it isn’t. Then you start asking yourself probing questions like, “What the hell is a faucett, anyway? And how are you supposed to wear it?” Myself had no answer, so I turned those who might: my role models in the Historic Knitting group on Ravelry.com. I’m a member, but mostly a quiet member. I sit on a little wooden stool in the corner, listen, and learn. There are serious scholars in there–professors of textile history, dedicated re-enactors, living history professionals. So I asked them, “What the hell is a faucett, anyway? And how are you supposed to wear it?” To say I was deluged with thoughtful, eager assistance is to understate the case. The group galloped to my rescue like a cavalry mounted on antique spinning wheels.* I had messages from no fewer than forty-three expert knitters in the space of six hours. They provided me with an excellent answer to the second question, and some fascinating theories about the first. The way to wear a faucett turned out to be no great mystery. In the mid-19th century, short, slender scarves (usually woven, less often knit or crocheted) were a common adornment. The enormously helpful mrsmcknittington was first to direct me to images like this, showing the garment in action. Pinning down the name was more of a challenge. Not a single instance of the term “faucett” (or likely variations such as “faucette,” “fawcett,” or “faucet”) was to be found in any of the dozens of costume histories to which the researchers had access. In fact, nobody seemed to be able to find it anywhere except right there in Mrs. Gaugain’s pattern book. Such is the vague and shifting nature of fashion terminology. Without hard evidence, the best one could do was theorize, and so one did. The most intriguing notion was that faucett might be derived from a proper name. It could have been that a Miss or Mrs Faucett–perhaps an Edinburgh society darling who shone brightly for a season–had worn the scarf with such élan that her name became associated with it. Fashion loves to do this sort of thing. In the nineteenth century, the famous soprano Henrietta Sontag lent her name to a wildly popular style of triangular shawl. In our own time, we have the Kelly bag and (less glamorously) the Mao jacket. Faucett might also have been a dressmaker or costumier who made the accessory such a signature that she (or he) and it became inseparable–like Chanel and her suit, or Stetson and his hat. Or Amelia Bloomer and her…well, you know. Unfortunately for this theory, what hasn’t turned up (yet) is any mention in the historical record of the original Faucett. She may be there–perhaps in a faded newspaper account of the guests at a fashionable gathering–but unless we find her, she remains only a theory. Less romantic, but also less speculative, is the derivation put forth by multiple researchers who very kindly combed stacks of dictionaries on my behalf. They pointed to the Latin word** faux (in the singular, fauces) meaning…throat. Hmmm. Fauces survived the classical era in derivations like the Old French fausett (the hole or tap in a cask); and persisted into modern times as the medical term faucal (of, or pertaining to, the throat) and, of course, faucet (the neck-shaped thing in the bathroom that pours water into the sink). It’s not a stretch, is it, to suppose that the garment might be named after the body part it wraps around? We have leggings, don’t we? And wristlets? And booty shorts? For whatever reason Mrs. Gaugain found herself unable to call this thing a scarf, she nonetheless turned out a scarf pattern that is simple without being dull.*** And when I say simple, I mean simple. This is the first pattern I’ve ever translated for which the notes are longer than the instructions. The stitch motif is one row long, and it wasn’t until I’d knit about four inches of it that I recognized it to be what it is–a member of the brioche family. But not the brioche I’d learned, which took three paragraphs and two diagrams to explain; and was about as much fun as removing your own tonsils with a pair of tweezers. Nope. Mrs. Gaugain gets her version across in less than half a line, and it’s so easy you can knit it while chilling with your posse in a dark biker bar. The clever woman also realized that when you block brioche as though it were lace, it suddenly appears to be this Whole Other Stitch; and very pretty it is, too. Try it for yourself, and see. *This simile works best if you don’t think about it too hard. **Which I also found, after the fact, in the Latin dictionary two feet from my writing desk. Boy, was my face red. ***Every woman who has visited the workroom during the past month, and seen the faucett draped around the neck of my dress form, has either asked to have it or tried to steal it, or both. If you have a smallish amount of luxury fiber that you want to use and show off, here’s your answer. |

|

|

translated by Franklin Habit,

from The

Knitters’ Friend by

Jane Gaugain

|

|

FINISHED MEASUREMENTS |

Length: 61 inches (excluding fringe) |

|

MATERIALS Notions |

| GAUGE |

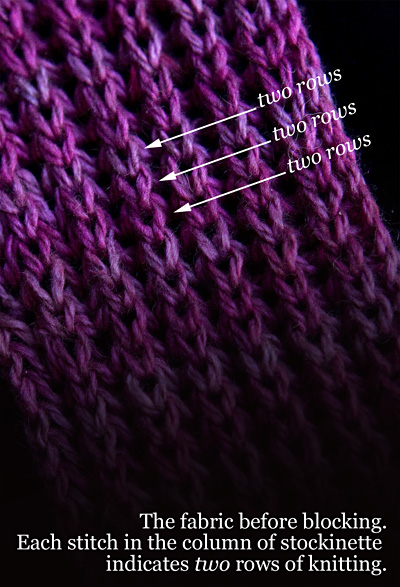

20 sts/28 rows = 4 inches in stockinette

stitch |

|

PATTERN NOTES |

The piece is worked flat, wet blocked, and then seamed along its length before being finished with knotted fringes at each short end. Casting on: This piece requires firm blocking (such as is normally employed on knitted lace) in order to bring the fabric to its final appearance and dimensions. It is therefore vital that the CO and BO be done loosely. I recommend using needles 2 sizes larger than the pattern requires for both. Alternatively, CO using the long-tail method over both needles held together in the right hand. Yarnover at beginning of row: Bring the working yarn from front to back over the right needle before working the next stitch.  Joining a new color: Mrs. Gaugain calls for the knitter to “tie on” a new color when it is introduced on a RS row. I prefer, instead, to thread the strand of the new color onto a yarn needle and weave it lightly into the WS of the fabric near the edge of the work, so that the first maneuver of the row (a yarnover, because of the pattern stitch) can be performed. This initial weaving can be neatened up during the finishing process. Carrying Unused Colors While Striping: Mrs. Gaugain is mum on the subject of what to do with the unused color while working the stripes at either end of the faucett. As each stripe is 12 rows deep, simply letting it hang is unsatisfactory. You could break each color as the stripe ends, leaving a tail, and join in the new color; but that will create a lot of loose ends to weave in. I prefer to leave the unused yarn attached, and pick up the working yarn from underneath it at the beginning of each RS row. This traps the unused yarn against the selvedge, and as the piece progresses the extra color will more or less disappear into the fabric. When it’s time to switch colors again, the new yarn will be exactly where it needs to be. Information on blocking can be found here. Information on mattress stitch can be found here. A guide to making knotted fringe is available here. Historic sizing: The original pattern calls for both of its variations to be worked to a total length (excluding fringes) of three-quarters of a yard, or approximately 27 inches. Historic colors: The original pattern, which calls for Berlin wool (substitute fingering weight yarn), suggests Albert blue (a bright, rich blue somewhere between royal and lapis lazuli) with stripes of “fire colour”–presumably reddish-orange. Historic variation: Mrs Gaugain offers a

finer version of the pattern, worked in Berlin embroidery silk

(as a substitute, try a silk or silk-blend two-ply lace weight).

Using needle approximately size US4 or 5, CO 30 sts and follow

pattern as written. Suggested colors are pink with white stripes

and fringe, or all black. Block the finished piece to three

inches wide, but do not seam. |

|

|

DIRECTIONS |

|

With MC, loosely (see Pattern Notes) CO 21 sts.

First Stripe Section: See Pattern Notes for tips on joining the yarn and handling

the color change. Row 25 [RS]: With CC, yo, sl 1, k2tog. With MC, [yo,

sl 1, k2tog] to end. Repeat Rows 13-36 once more, and Rows

13-24 again. 3 MC stripes,

3 CC stripes. Plain Section: Second Stripe Section: BO loosely (see Pattern Notes). FINISHING When dry, weave in ends. Fold long selvedges to lengthwise center, and use mattress stitch to seam selvedges together; piece will now be a long, flat tube with open ends. Using eight 7-inch lengths of CC, finish short edges with fringe, knotted or not according to your preference. |

|

|

| ABOUT THE DESIGNER |

He thinks this darling little bandeau will look positively spiffing with his motorcycle gear. |

| Pattern & images © 2011. Franklin Habit. |