|

| Fetching mitts

knit from Navajo-plied merino hand-spun |

Once everyone in the

family is sporting a fabulous chunky hat, and

the bookcase is overflowing with skeins which

you put on display because they are “just too pretty to make anything out

of”, you may find yourself wondering what

else you can do with your hand-spun yarn.

There is a limit to the

number of scarves we and our families need,

so unless you wish to design from scratch every

hand-spun article you make, you will probably

be asking yourself whether you can substitute

hand-spun yarn in one of your favourite knitting

patterns. The answer is, of course, yes.

In

this article you will discover how to spin

a consistent yarn and achieve the gauge required

by the pattern you have in mind. We will also

look at the composition of some popular yarns

and discuss how to achieve a successful match.

You may even find some ideas for using up some

of those “too-pretty” skeins

to make room for the next exciting batch!

Not every commercial yarn can be replicated

exactly. Factories have spinning and plying processes

available to them which can hardly be achieved

on a domestic wheel, however, with a bit of ingenuity

you can come up with something that has a similar

gauge, composition and hand to the original yarn.

Gauge,

naturally, is most important. You cannot begin

to think about replacing a recommended yarn

if you don’t match the gauge -– just

as you wouldn’t substitute a mis-matched

commercial yarn. Don’t be discouraged,

though; it is not as difficult as you might think

to spin to a specified gauge: Just follow these

steps:

- Decide whether your yarn will be singles,

2-ply or 3-ply. This will depend on the yarn

you are trying to match, and the effect you

wish to achieve.

- Refer to the gauge table to see how thick

your singles should be spun.

- Spin a test length and measure the wraps

per inch (wpi) both in the single and after

plying. Even if the wpi is correct, knit a

swatch as well for extra reassurance.

- Keep your sample of singles handy while you

spin so you can regularly check for consistency.

Remember:

- Always measure a whole inch – do not

be tempted to stop at a quarter or a half and

multiply. Every wrap counts!

- The amount of twist in your yarn will affect

the gauge and wpi so make sure you spin your

sample as you plan to spin the whole skein and

make notes of wheel ratio and tension.

- In fact, keep notes on everything you do! You

will thank yourself when you want to replicate

your hand-spun later.

Weight |

Laceweight |

Fingering |

Double

Knit |

Worsted |

Gauge |

variable |

28sts

= 4in |

22sts

= 4in |

18sts

= 4in |

wpi – for

singles |

22 |

16 |

13 |

10 |

wpi – for

2-ply |

44 |

32 |

26 |

20 |

wpi – for

3-ply |

55 |

40 |

32 |

24 |

Composition can

be anything from easy to impossible, to match.

Many of the yarns we knit with are made of wool,

much of the fiber we spin is wool -– simple!

Fancy yarns and acrylic blends, however, may

require a bit more imagination to create something

similar. Don’t be afraid

to experiment and ‘fudge’ your fibers

a bit to achieve a similar yarn. With experience

you will find there are many ways around a tricky

composition -– and you may even like your

version better.

Hand is

the ‘feel’ of

the yarn and finished fabric. A tightly spun

cotton yarn feels completely different to a soft

singles of the same thickness. The number of

plies, the amount of twist in the yarn and the

finishing process will all affect the way your

knitted fabric feels and drapes. Once again,

experimenting with small amounts is the best

way to find hand that you like, and you’ll

soon find you get a ‘feel’ for creating

a certain type of yarn.

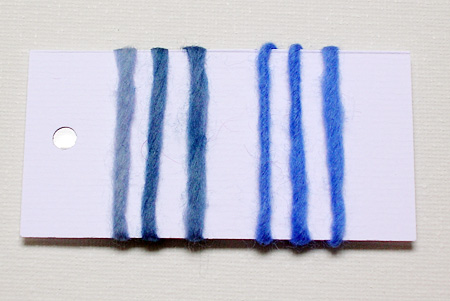

I

chose three popular wool blend yarns

to experiment with, opting for varying gauges,

compositions and purposes. The first is a worsted-weight,

softly textured yarn, popular for warm wintry

garments. Second, a favourite lace-weight yarn

which combines mohair fuzziness with the shimmer

of silk. Finally, a standard double knit yarn,

just the kind of thing you might choose for a

fall cardigan or a soft baby sweater.

Worsted Weight

It is apparent at first glance that this is

a singles spun yarn, and it is quite soft and

slightly fuzzy. The ball band states only that

it is 100% wool, but from the soft feel and what

I know of its felting properties, I am almost

certain it is merino, easy to find in my stash.

Gauge is straightforward, simply a matter of

keeping a small strand of the yarn close by while

spinning to make sure I match the thickness.

What I felt was important with this yarn was

to achieve the same thick softness and fuzziness

of the original. This called for a low-twist,

woollen-spun singles. I set my wheel on the lowest

ratio to minimise twist and pulled off short

lengths of merino roving, fluffing them out slightly

before spinning them from the fold.

Commercial

worsted yarn (left) and hand-spun (right)

To help the yarn stay together and tame the

twistiness of the singles, I treated it to a

shock-and-whack treatment after winding off my

skein. This involved plunging the skein alternately

into hot and cold water and then whacking it

against the kitchen cupboards! In a soft singles

this felts the fibres slightly, helping to reduce

wear later and bringing out a fuzzy bloom on

the yarn.

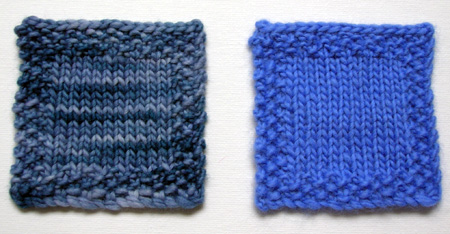

Swatches from

commercial worsted yarn (left) and hand-spun

(right)

After blocking, the appearance and hand of the

two swatches is almost identical. This is an

easy yarn to replicate and, being a singles,

allows great scope for playing with color and

texture in your planned garment.

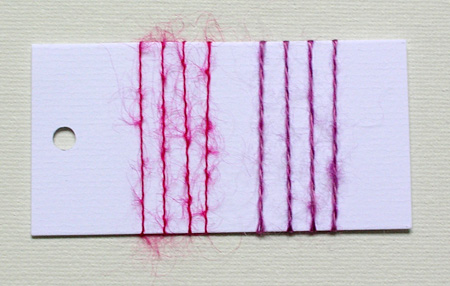

Lace Weight

As

the lace-weight yarn knits up into a very open

fabric, I allowed myself a bit of leniency when

it came to composition and spinning. Firstly,

the commercial yarn is a blend of 67% mohair,

18% silk and 15% synthetic. That’s a lot

of mohair! What I might have done is spin a very

fine single of pure mohair, then a very fine

single of pure silk and ply them with a commercial

nylon thread to hold it all together. This did

not appeal to me – mostly because pure

mohair and I don’t really get along.

I chose instead to blend 50% kid mohair with

50% merino/silk blend using hand cards. The resulting

fluff was far more manageable than pure kid,

with the small amount of wool being just enough

to reduce the slipperiness. I set the wheel ratio

to high for maximum twist and spun very slowly

and as finely as possible, keeping an eye on

the fibres so the longer mohair did not creep

away leaving a pile of wool behind.

Commercial

lace-weight mohair yarn (left) and hand-spun

(right)

I plied the singles back on itself and then

treated it also to a good whacking to encourage

the mohair to bloom.

Swatches from

commercial lace-weight mohair yarn (left) and

hand-spun (right)

The hand-spun yarn is slightly

heavier and has a little less halo than the commercial

lace-weight (more halo than appears in the photo,

though). However, when knitted on the same needle

size and blocked, the swatches are not dissimilar.

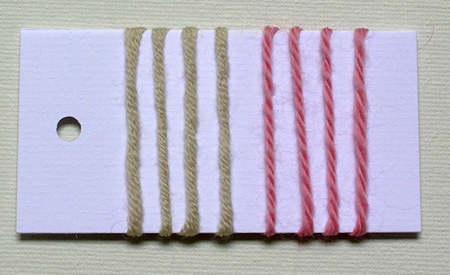

Double Knit

This yarn is soft and bouncy with excellent

stitch definition and is my current favourite

for cable work. The crispness in the cables is

due to the almost perfect roundness of the yarn,

in this case, achieved through many very fine

singles being wrapped around a central core.

To replicate this as closely as possible, I chose

a superfine merino from my stash and spun a fine

singles for a 3-ply yarn.

Commercial

DK yarn (left) and hand-spun (right)

The 3-ply has a nice roundness which closely

resembles the commercial sample. In the swatch,

it shows clear, crisp stitch definition.

Swatches

from commercial DK yarn (left) and

hand-spun (right)

When dry, there is a slight difference to the

hand of the swatches: the commercial yarn is

a little softer. The handspun is still very soft,

however, and would feel great knit up as a sweater

or close-to-skin accessory.

Spinning your own yarn

for a pattern opens up a whole new world of

possibilities in color, texture and design.

You can plan exact color placement or spin

a little bit of textured yarn to use as a feature

in part of the garment. Don’t

be afraid of the time involved: in my experience,

it takes less time to spin two ounces of fiber

than it takes to knit up the same amount of a

similar yarn. And the satisfaction of having

created something completely from scratch will

stay with you forever!

|