First amendments:

altering length in a knitting

pattern

There's nothing

like a technical article to make

something sound more complicated

than it really is.

You're planning

to knit a sweater, but looking

at the finished dimensions it

seems that by following the instructions

as written, the sweater will come

up a little short on your body,

or perhaps a little long. You

might conclude that the solution

is to add (or subtract) enough

rows of knitting from (or to)

the pattern to make the sweater

the right length, and that no

further thought is required. And

assuming that your sweater is

knit from bottom to top, or top

to bottom, that's absolutely right.

But when the

design incorporates shaping, textural

stitch patterns, or colourwork,

adding or subtracting rows might

not be quite as straightforward

at it seems. What if the length

alteration interrupts a cable

repetition? What if it cuts into

a band of Fair Isle patterning?

There might be placement issues:

where is the adjustment actually

needed? In the upper body, above

the waist, or below the waist?

There might be shaping issues:

how should increases or decreases

be respaced? Are there any consequential

amendments that need to be made

to other pieces that are joined

on to the lengthened/shortened

piece?

And maybe you

only need extra length in a certain

area, and not an overall length

alteration is needed at all. Sometimes,

adding an inch or two of length

is used as a panacea for other

fitting or style problems. (This

is true of adding width, too.)

If you find that your sweater

fronts ride up too much compared

to the back, the solution isn't

necessarily to add length all

around; the solution might be

short row bust (or belly!) shaping

instead.

So here, we'll

take the long, analytical approach

to length alterations, which we

can summarize in four deceptively

simple questions:

- How much

length do you need to add/subtract?

- Where do

you need to add/subtract it?

- How can you

add/subtract this length while

causing the least disruption

to the design?

- Do any other

pieces need to be altered as

a result of this addition/subtraction?

We're not really

addressing significant alterations

that affect the overall style

of the garment. For example, you

might be working from a pattern

for a waist-length jacket that

you want to lengthen to fingertip

length -- that's a more substantial

alteration that will affect the

look of the jacket, and perhaps

skew the balance of the design.

Here, we're talking about length

alterations that are intended

to preserve the original style,

but keep a wrist-length sleeve

from becoming an unintentional

bracelet-length sleeve.

In this article,

we'll address the first two questions.

The next two, we'll save for next

time.

How

much length do you need to add/subtract?

Determining

how much length to insert or take

away is relatively simple: given

that you likely already know what

your preferred overall garment

and sleeve lengths are, compare

them to the pattern's finished

dimensions and do some simple

math.

Your preferred

lengths: When it comes to

preferred body length, you probably

have a series of preferred lengths

that you know you're comfortable

with and look good on you: one

for loose, casual sweaters and

cardigans, one for tight-fitting

tops, one for close-fitting, dressy

sweaters, and so on. This doesn't

mean that you've got these lengths

committed to memory. It means

that you're aware that different

styles of clothing look best at

different lengths, and that you're

not fixated on making every

single pullover or cardigan you

knit the same length.

As part of this

awareness, you're probably cognizant

of the fact that in tops with

waist shaping, the proper location

of the waist shaping depends on

the location of your natural waist

-- the indentation between your

ribcage and your hips (or at least,

the place where you'd put your

hands if you were asked to put

your hands around your waist).

If you find that you need to lengthen

or shorten a pattern with waist

shaping, the location of that

indentation may be important to

know.

The vertical

location is usually expressed

in sizing charts as your back

waist length, which is measured

along the back between the base

of the back of your neck and your

waist. To find the base of your

neck, tilt your head forward slightly,

and feel for the most prominent

bone jutting out of your spine.

That measurement isn't quite a

true vertical measurement because

the spine is naturally curved,

but for the purpose of most hand

knitted items, it's close enough.

For some individuals with rounded

shoulders or a hunch, the difference

between the back waist measurement

and the true vertical may be more

significant.

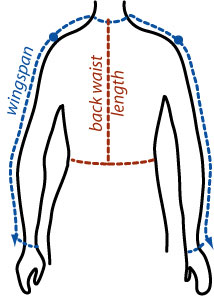

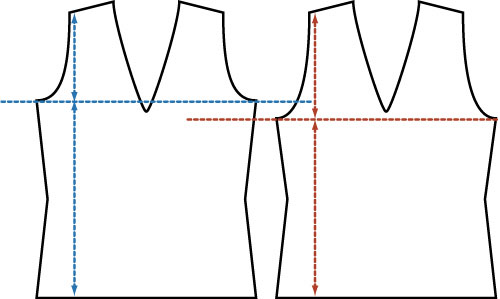

|

| The back

waist length (red) and the

wingspan (blue). The wingspan

can be broken up into two

sleeve lengths, plus the upper

body (cross-back) measurement. |

When measuring

for a full-length sleeve, make

sure that in addition to knowing

your ideal sleeve length for a

set-in sleeve (from the shoulder

joint to the wrist, with the elbow

slightly bent), you also know

your wingspan: the distance from

wrist to wrist, with elbows slightly

bent, along the shoulder and across

the back of the neck. Knowing

your preferred upper body width,

shoulder to shoulder, as well

as your set-in sleeve length,

is effectively the same thing.

The pattern's

finished dimensions: Ideally,

the relevant dimensions of each

garment piece -- front, back,

sleeves -- are provided in schematic

form. If they aren't, you'll have

to follow the pattern instructions

for your size and count the number

of rows worked, and do a spot

of math to calculate final lengths.

Either way, make sure that you

take any welting, ribbing, or

other hem treatment into account.

When taking the length of the

sleeve, also determine the width

of the upper body of the garment.

When determining

the length of the garment pieces,

keep a couple points in mind:

If you sew,

you might be accustomed to measuring

a scalloped or similarly shaped

hem from its highest point. In

knitting, because most lengths

are measured in terms of the number

of rows worked, changes are that

the length of the garment is reported

based on the distance to the lowest

point. In many cases, that won't

make a significant difference;

however, if the scallops or crenellations

are particularly deep or wide,

you may want to make sure that

the "shallow" portions are the

right length. For example, if

a full-length sleeve ends with

a scalloped edge, you will probably

want to estimate the pattern length

from the inner edge of the scallops,

not the outer edge.

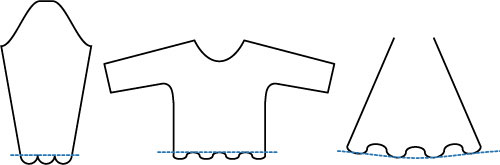

|

| When the

hem is shaped, make sure that

both the minimum length and

the maximum lengths are in

the right neighborhood. For

a long sleeve, the inner (upper)

edge of a scalloped hem should

match your preferred long

sleeve length -- don't measure

from the outer edge, or else

your sleeve may "feel" short.

But for a long skirt, make

sure that the outer (lower)

edge of the hem is still short

enough to avoid dragging on

the floor. |

Also, knitting

patterns often provide finished

garment lengths measured from

the top of the shoulder, and sometimes

from the top of the armscye. Frequently,

those numbers do correspond to

the base of the neckline, but

sometimes they don't. This means

that if you simply compare your

conventional back waist length

to the pattern's reported garment

length, you might mistakenly think

that the garment will hang lower

on your body than it would in

real life. For example, a knitting

pattern for a waist-length jacket

might claim to have a finished

length of 15 inches. If that 15

inches is measured from the top

of the shoulder to the hem, then

it will actually end above

the waist on a person with a back

waist length of 15 inches. We

frequently ignore this discrepancy

in hand knitting, because of the

overall fit of hand knitted garments

-- that length difference is often

unimportant.

So, there are

three ways to address this discrepancy:

either ignore it and assume that

your back waist length and the

garment length are "close enough";

or estimate your shoulder "depth",

from the top of the shoulder next

to the neck to a point at the

same depth as the base of the

back neck and add this to your

back waist length, or when determining

the length of the garment, estimate

where the base of the back neck

would lie and make your measurement

from that point.

With those caveats

in mind, the comparison of the

pattern dimensions to your preferred

lengths should be quite easy.

For the body length, compare one

of the two sets of numbers:

- your actual

back waist length vs. the length

of the garment measured from

the base of the neck, according

to the pattern

- your actual

back waist length + shoulder

depth vs. the length of the

garment measured from the top

of the shoulder, according to

the pattern

The difference

is the amount by which the pattern

must be lengthened or shortened.

For the sleeve

length, compare:

- your preferred

wingspan measurement (sleeve

length + upper body width +

sleeve length) vs. the wingspan

measurement of the pattern.

The difference

is twice the amount by which the

pattern must be lengthened or

shortened. Half of that difference

must be added or subtracted from

each sleeve. For example, if the

pattern wingspan is 60 inches,

but your actual wingspan measurement

is only 57 inches from wrist to

wrist, then you'll need to subtract

1.5 inches from the length of

each sleeve.

However, if

the sleeve is a set-in sleeve,

the length alteration that must

be made to the sleeve may be affected

by any necessary alterations to

the body -- see the discussion

below about determining where

length should be added or subtracted.

Where

do you need to add/subtract these

extra rows?

This is where

the actual shape of the

garment pieces is relevant.

Altering

the body length: If the body

is an unshaped rectangle without

an armscye (drop shoulder style),

then subject to texture or colour

pattern repeat issues, the extra

length can be added or removed

anywhere from the hem up to the

neck shaping.

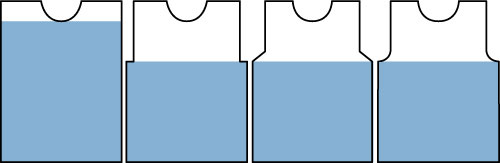

|

| In a plain,

rectangular body, you can

add or subtract length anywhere

below the neck shaping (blue

area) without affecting the

overall shape of the garment.

If the rectangular body has

an armhole indentation or

similar shaping (pretty much

any more or less rectangular

shape, other than a plain

drop shoulder), then the length

can be added or subtracted

easily anywhere between the

hem and the beginning of the

armscye area. |

If the body

is generally rectangular with

no waist shaping but with an armhole

indentation, as in a modified

drop shoulder or even a raglan

style, then chances are the armscye

is appropriately sized to accommodate

the body and requires no adjustment.

Typically, the fit of the entire

garment is loose, and a slightly

oversized armscye won't make much

of a difference. The length adjustment

can therefore be made anywhere

between the hem and the beginning

of the armscye shaping. This makes

the alteration easier: altering

in the armscye region would require

an alteration to the sleeve width.

Altering body

length between the hem and the

armscye also follows for dolman

styles and set-in styles. For

dolman styles, the fit at the

shoulder joint is loose, so small

adjustments would not make a noticeable

difference in fit. For set-in

styles, the armscye depth is usually

appropriately sized already, and

while individuals vary in back

waist length measurements, that

variation can be accounted for

by altering the length below the

armscye. On rare occasions, the

set-in sleeve armscye may be tight

and binding, requiring a length

adjustment to increase the armscye

depth, or a width adjustment to

make a bigger armhole. In that

case, the overall length of the

body will be affected, so consequential

alterations to the rest of the

body length may be necessary.

|

| There are

circumstances in which precise

fit counts, and the armscye

depth may need to be adjusted.

If the armscye is made deeper,

as in the diagram to the right,

then the rest of the body

will need to be shortened

to preserve the overall length.

|

If the body

has waist shaping, however, you

might want to consider how your

body's vertical measurements deviate

from the vertical measurements

in the pattern. Depending on your

body shape, you might want to

add or subtract your rows above

or below the waist indentation.

If you're especially

long-waisted (have a longer than

average back waist length measurement)

and you've determined that you

need to add length to the garment

body, you might want to insert

your extra rows between the waist

and the beginning of the armscye

rather than at the hem. Similarly,

if you're noticeably short-waisted

and you find that you need to

shorten the garment body, you

might want to subtract those unnecessary

rows above the waist. But if the

back waist length of the pattern

matches your own back waist length,

then that length alteration would

be more appropriate between the

waist and the hem. In knitting

patterns, the indentation at the

waist is often an inch or two

wide. This means that a minor

length alteration might not adversely

impact the overall positioning

of the indentation, so you can

get away with making the length

alteration at the hem, which is

often easier.

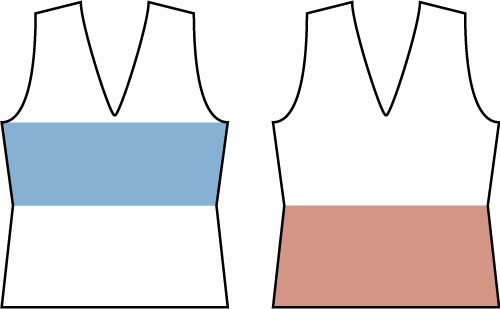

|

| When a garment

has waist shaping, make sure

that the length alteration

keeps the waist indentation

around your own waist. For

a significant long-waisted

or short-waisted alteration,

consider making the length

adjustment above the waist

(blue area). If your back

waist length matches the pattern's,

then the length adjustment

is made below the waist (red

area). |

Altering

the sleeve length: While

you may have determined the total

length to be added or subtracted

to the wingspan, that translates

directly to a sleeve length alteration

only if the upper body

width does not need to be altered.

In the case

of a garment without a set-in

sleeve, such as a drop shoulder

pullover, the upper body width

will likely be broader than your

actual, preferred, upper body

width, and no adjustment would

be made to the upper body width.

Differences between the pattern

wingspan and your preferred wingspan

measurement will be adjusted in

the sleeve length, as described

earlier; half of the wingspan

differential will be added or

subtracted to each sleeve.

In the case

of a set-in sleeve, you should

first determine whether the upper

body width is appropriate; if

it is, then any length adjustment

that needs to be made should be

made in the sleeves. If the upper

body width in the pattern needs

to be adjusted (which is actually

a width alteration, not a length

alteration), then this may impact

the sleeve length alteration.

So, you'll also need to compare:

- your preferred

upper body measurement (shoulder

to shoulder) vs. the upper body

measurement of the pattern

These should

be approximately the same in a

close- or slim-fitting style,

not taking into account any selvedge

stitches that would be worked

into the armscye seam. In some

classic-fitting or casual styles,

the armscye seam may not ride

exactly at the shoulder point,

but may fall slightly lower on

the arm -- but not by very much,

no more than about half an inch

depending on the thickness of

the fabric. If the upper body

measurements in a set-in sleeve

style differ significantly, then

the pattern should be altered

to bring this measurement in line

with your preferred size. This

might be done by choosing a different

pattern size, but it may also

be done by altering the width

of the body.

If the width

of the body is altered in order

to broaden or narrow the pattern's

upper body measurement, then this

will affect the total wingspan

measurement of the pattern: after

alteration, check again to make

sure that the pattern wingspan

matches your preferred wingspan

measurement. If it still doesn't

match, then the sleeves will have

to be shortened or lengthened

by half of the difference

in wingspan measurements. Just

as in the example described earlier,

a wingspan difference of 3 inches

translates to a length alteration

of 1.5 inches on either sleeve.

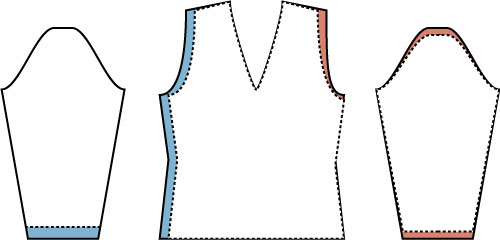

|

| In a long-sleeved,

set-in sleeve style, not only

should the pattern and body

wingspan measurements match,

but also the pattern and actual

upper body measurements. If

the upper body width is altered,

then a length alteration may

be required in the sleeves;

the nature of the alteration

will depend on whether the

armscye shape is affected

or not. On the left, the armscye

shape is preserved; any length

adjustment can be done below

the sleeve cap (e.g., at the

cuff). At right, the armscye

shape was altered; adjustment

may be necessary at the cap,

as well as below the sleeve

cap. |

Whether the

sleeve is a set-in style or not,

the length adjustment will be

made somewhere between the hem

and the beginning of the sleeve

cap shaping, not in the sleeve

cap itself. The sleeve cap shaping

will only be adjusted if the armscye

itself is altered.

Next

issue: Altering length and minimizing

design interruptions, and consequential

amendments