I used to like row-by-row

instructions. They told me what stitches to

make, and I made them. It was very simple.

But then I bought a kit for a lace shawl,

and the directions came as charts. No problem,

I thought: I just covered up the rows I hadn't

made yet, and pretended that each row of the

chart was a set of instructions that someone

had written out in a strange language. Annoying,

but if I could learn what "k2tog"

meant, I could learn that "/" meant

the same thing.

And then I realized what

I was missing.

With row-by-row instructions

for, say, seed stitch, you alternate knits

and purls. But if you make one mistake, then

suddenly all of your knitting is off, and

half of a row will be worked in broken ribbing

instead. On the other hand, when presented

with a chart of seed stitch, I know to work

knit stitches into purl stitches only. I can

catch my mistakes, quickly, because the chart

will tell me where my next stitch is to be

worked.

At this point, I'm in love

with charts; for any kind of complicated pattern,

I'd rather work from a chart than from written

instructions. Unfortunately, I keep coming

across patterns with no charts. So I started

making my own. And here is what I know.

Everyone means the same

thing by "k2tog," and every pattern

writer uses "k2tog" as an abbreviation

for "knit the next two stitches together."

Unfortunately, charts are nowhere near as

simple. Different people use different symbols

to mean the same stitch, or use the same symbol

to mean different stitches. Sometimes, there's

a good reason for this.

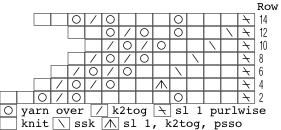

In lace patterns, the important

point is the gaps and the decreases; the symbols

for plain knit and purl both need to be small

and unobtrusive. In textured patterns, on

the other hand, the whole point is the contrast

between knit and purl; hence, they have to

look very different.

And sometimes there's no

reason for symbols in two charts being different.

As should be obvious from

all of this, it is absolutely essential that

you include a key with your pattern or chart,

to tell your readers what you intend a dot

or slash to mean.

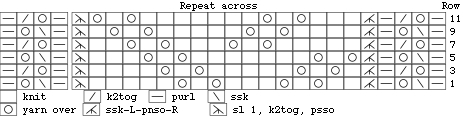

Here's a listing of some

common symbols that I've seen in American

patterns -- in some cases, different publications

use a different symbol, so you'll see several

for each category. While there's no logical

reason why you couldn't use, for example,

an ampersand (&) to mean k2tog, most readers

will find it easier to read your chart if

your symbols look like symbols they've seen

before.

Knit one stitch

Purl one stitch

No stitch. In some patterns, using this symbol

properly is essential.

Yarn over or make a bobble

Knit two stitches together

Any left-sloping single decrease: ssk, k2tog

through back loop, or slip one, knit one,

psso.

A left-sloping double decrease, such as k3tog

through back loop.

A double decrease that doesn't slope very

much to either side.

A right-sloping double decrease, such as k3tog.

Cables

My first lace project was

the Petal Sonnet shawl from Blackberry Ridge

designs. In the shawl is a large water lily

pattern, designed specifically for this shawl

by Hazel Carter. To get the look she wanted,

she had to let her petals flare out drastically.

This meant that she had to change the stitch

count of her pattern from row to row. To chart

this, she had to include a lot of blank squares

in her chart. Because the spaces were distributed

irregularly, the chart was hard to read: I

had to treat it as row-by-row instructions,

which meant (for me) that the main point of

using a chart was lost.

Most patterns do keep the

stitch count consistent from row, but even

in this case, blank squares at the edges may

be necessary. A triangular shawl will need

to have a steadily-increasing number of blank

squares on the edges; an edging may need blank

squares added to its outside edge to keep

the inside edge straight.

Cabled or lace patterns

which increase or decrease the stitch count

will need rows of blank spaces inside the

chart, not at the edges. An excellent example

is the Twining

Trees chart. Charts of garments which

taper or flare may also need spaces in the

middle of the chart.

To figure out where to put

blank squares, remember that a chart should

show roughly which stitches are worked into

which other stitches. Add spaces so that symbols

in later rows end up above, or at least near,

the symbols for the stitches into which they

are actually worked.

A chart should include all

of the necessary information, but does not

need to include absolutely everything. There

are a number of things that can be left out.

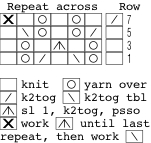

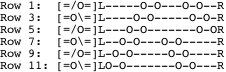

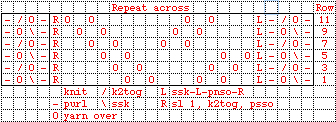

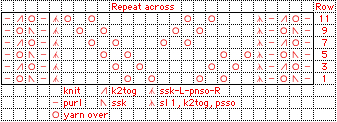

One example is repeats:

the charted equivalent of "*k2, p2, repeat

from * to end." To get more mileage from

repeats, don't be afraid to use symbols that

change meaning. Consider line 7 of Cozy.

The last stitch in each

pattern repeat is a double decrease, except

for the final repeat, where the last stitch

is a single decrease. Rather than writing

out the pattern twice to show this (nearly

doubling the width of the chart), it is perfectly

fine to use one symbol to mean a double decrease

in internal repeats and a single decrease

in the last one.

Also, you don't need to

show every row. If all even rows can be summarized

by quick directions, leave them out of the

chart. Put them in the pattern or next to

the chart. If you do it, bear in mind that

your chart might start to look squashed compared

to your knitting. To fix this, if you can,

make the cells of your chart twice as tall

as they normally would be.

Well, we know what we want

our chart symbols to look like. We know how

to arrange blank spaces, and we know what

we can leave out of a chart. How do we make

a chart?

My favorite tool for making

charts is a word processor: I just type my

charts in, one row per line. If you use a

fixed-width font such as Monaco or Courier,

your characters will line up into neat grids

on their own. Alternatively, if you like the

look of charts with a lot of space, you can

put a tab between every pair of symbols to

line them up.

If you don't mind your charts

reading from the top left, you can convert

written patterns to charts fairly quickly

using the "find and replace" function.

I've done this with charts as complicated

as Mon

Petit Chou, with very little editing by

hand afterwards. This method has the most

options for publishing on the web. You can

display your chart as text, since that's all

it is. Alternatively, you can take a screen

picture as for a spreadsheet. Also, most drawing

programs (MS Paint, AppleWorks, and Adobe

Photoshop, for example) will let you type

in your chart and then save it as a JPEG or

GIF. This is especially useful if you use

unusual fonts.

You can find symbols that

look like many of the standard symbols on

the keyboard: dashes, Os, slashes in both

directions, blank spaces. However, you will

not find any letters that resemble the symbols

for double decreases or cables.

You can deal with this two

ways. You can use letters instead of symbols,

or you can download a font with the symbols

you need already in it. For typed charts,

I recommend using David

Xenakis's fonts. Simply download the font

and install on your computer. About.com has

tutorials for installing fonts on Windows

and on Macintosh.

Another way to make a chart

on the computer is to use a spreadsheet: one

symbol per cell, with cells scaled appropriately.

You can even adjust the cell dimensions to

be the same shape as your stitches.

Spreadsheets are easy to

edit. You can insert rows or columns, or copy

and paste large rectangular chunks of stitches.

Inserting a new column into a word processor

can be annoying.

As with typed charts, you

can make your charts look better by using

a better font. In a spreadsheet, I like to

use the font from Aire

River Design. To turn your spreadsheet

into a JPEG image file suitable for web publication,

your best option is to take a screen picture.

Your computer may have come with a program

which will take screen pictures. If not, a

Google search for "screen capture"

and your computer's operating system will

probably yield a shareware or freeware program

which will take screen pictures.

When all else fails, go

back to a good old pencil and a piece of paper.

This method gives the pattern writer the most

control over the finished result. You can

use any symbols you can draw to represent

your stitches. If you're charting a pattern

that uses a lot of unusual stitches, this

can be very useful. These charts can be done

easily on ordinary graph paper.

However, if you want your

chart to look a bit more like the finished

product, you can also print out some knitter's

graph paper. This is graph paper which has

been stretched out so that the boxes are the

actual proportions of knit stitches.

This

page will make graph paper to fit your

gauge. Unfortunately, the only way to make

a paper chart into a digital chart is a scanner.

Either you have one and can do it, or you

don't, and can't. Also, depending on your

handwriting, your readers might be grateful

for a typed chart.

However you make a chart,

anyone following your design who likes charts

will be grateful that you did.