|

By

Shannon Okey

Looking

for a new challenge? Bored with commercial yarn? Do

you have sheep or other fur-bearing animals around

the house? You're a handspinner waiting to happen.

Like knitting, it's not nearly as difficult as

it appears to the novice, but you can spend years

perfecting complicated techniques while conquering

exotic fibers, dyes and different types of spindles

or wheels along the way.

This

article will address the basics as I know them.

I started to spin last year, and my experience

is based on an Ashford Kiwi wheel with sheep

fleece. I will take you through the first project

I made [a handspun, handknit pullover] and explain

the terminology, equipment, and methods.

The

first decision to make was "spindle or

wheel?" You can learn to spin very inexpensively

using what's called a drop spindle. A wood spindle

costs around $20, or you can make

your own with an old CD. Interweave Press

offers an article about beginning handspindling

called Low

Tech, High Satisfaction on their site.

Being

the impatient sort, I knew a spinning wheel

would allow me to meet the ambitious timeline

I'd given myself for my first project. There

are as many types of wheels as there are spinners,

and you're really only constrained by cost.

After searching for a used wheel online at The

Fiber Equipment and Barter Page, I ended

up with an Ashford

Kiwi. Ashford is a family-run company in

New Zealand, and they have half a million satisfied

customers worldwide. The Kiwi is a great beginner's

wheel, and I'm really pleased with mine. Schacht

and Louet are other well-known wheel manufacturers;

ask around if you're thinking of buying your

own.

If

you like fairytales, you'll love the names of

a spinning wheel's components. There are maidens,

footmen, Lazy Kates, the mother-of-all and distaffs,

among others. Check out The Woolery's article

on choosing

a wheel for illustrations of these parts.

After

you've chosen your wheel or spindle, you'll need fiber.

Most beginning spinners choose sheep's wool, because

it is the most forgiving of error and easiest to handle.

My teacher, Lucy Lee of Mind's

Eye Yarns, helped me pick out a fleece from a

sheep named Eddie at Rivercroft Farm in Starks, ME.

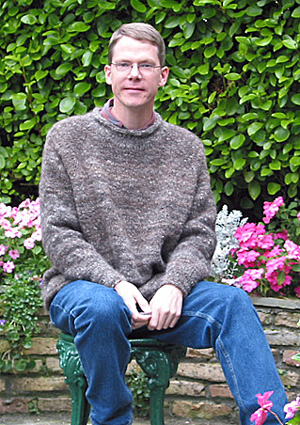

This project became known as The Eddie Sweater for

that reason [see right, modelled by my friend Lee].

Lucy recommended a Romney fleece [Romney is one type

of sheep, others include Merino, Corriedale, Lincoln

and Shetland] because it has a long staple length.

Staple length refers to the length of the individual

fibers. Longer is better when you are first learning

to spin because it is easier to draft without breaking

your single every few feet. [Don't worry; explanation

to follow]. After

you've chosen your wheel or spindle, you'll need fiber.

Most beginning spinners choose sheep's wool, because

it is the most forgiving of error and easiest to handle.

My teacher, Lucy Lee of Mind's

Eye Yarns, helped me pick out a fleece from a

sheep named Eddie at Rivercroft Farm in Starks, ME.

This project became known as The Eddie Sweater for

that reason [see right, modelled by my friend Lee].

Lucy recommended a Romney fleece [Romney is one type

of sheep, others include Merino, Corriedale, Lincoln

and Shetland] because it has a long staple length.

Staple length refers to the length of the individual

fibers. Longer is better when you are first learning

to spin because it is easier to draft without breaking

your single every few feet. [Don't worry; explanation

to follow].

When

you buy a raw fleece, a good farm or supplier will

have skirted it, or removed the dirtiest, most matted

pieces along the edges. A fleece is quite large [I've

made 2 sweaters from Eddie's so far], weighing

anywhere from 4 to 10 pounds. Good fleece is expensive,

but compared to finished yarn, quite reasonable, not

to mention absolutely unique! You can expect to pay

at least $5 per pound and up.

Before

you get started, you'll need to wash the fleece.

Surprise! In addition to their skin's natural

lanolin and other oils, sheep sweat. They sweat

a lot, actually. And there will be dust and

dirt on even the cleanest fleece. Although I've

read many articles that suggest using dishwashing

soap, I took Lucy's advice and used human shampoo.

Those economy bottles of lavender-scented Suave

are great!

Like

washing a finished wool sweater, you never want to

alternate between hot and cold water, or you will

be learning to felt instead! In this context, felting

is bad. Felting intentionally tangles fibers and that's

not what we're trying to do.

Basic

fleece-washing rules include:

-

Choose

either hot or cold water and stick with it. I'd

go with hot. It should be hot enough to be uncomfortable,

but not so hot you burn yourself. You also need

to maintain the temperature, so be prepared to

work quickly.

-

Put

in a good amount of shampoo, but not so much you

end up rinsing the fleece 10 times. Take out too

much of the natural oils and the fleece becomes

more difficult to spin.

-

Don't

crowd the fleece. I wash it in my bathtub, and

one whole fleece was divided into at least 8 sections.

-

When

the water is ready, float the fleece on top of

the water and push it under gently. Don't

agitate the fleece, you'll inadvertently

felt it!

-

Lift

out sections of fleece with a wooden spoon

handle or similar and employ Shannon's Lazy

Method of Drying. Let gravity do the work:

on your balcony rail or a wooden clothes

rack, drape individual segments of fleece

you've scooped out [they'll look

like long locks of hair] and leave them

until dry. A sunny windy day is best. Added

bonus: less carding! If there's a little

soap left on the wool, that's ok.

Carding

is the next step. Carding aligns all the fibers in

one direction and fluffs them to make drafting easier.

There are different methods and different tools for

carding, including combs, hand-cranked/electronic

carders and carding paddles. I use paddles. If you've

used Shannon's Lazy Method of Drying, you might

not need to card much. As the water drips out of the

drying locks, it pulls the fibers in one direction

and, if you're careful, you can draft straight

from a dried section. Otherwise, take a piece of your

clean, dry fleece [it must be completely dry —

don't forget wool's amazing ability to hold

water] and "charge" a paddle by draping

pieces of fleece in one direction. You'll then

take the other paddle and gently swipe across the

fibers, aligning them in one direction. When everything

is fluffy and aligned, pull the fiber off and put

it aside. Sometimes you'll need to pick apart

stubborn individual locks with your fingers. When

I first started to card, I had a tendency to over-card.

You don't want to beat the fibers into submission,

just make them presentable.

Now

you have a giant pile of clean, wooly puffballs. It's

time to spin! After attaching a leader, or

starter piece of yarn, to your bobbin, and pulling

it through the orifice, you wrap the edge of a puffball

around the leader, pinch it and start to work the

treadles with your feet. Most spinners spin clockwise

and ply counter-clockwise. As the fiber starts to

wrap around the leader, you begin to draft. Drafting

is pulling fiber out with your free hand from the

puffball so it can twist itself into the yarn that

is beginning to wind onto the bobbin. If you're

right-handed like me, you'll hold the puffball

on your left, guide the forming yarn with your left

hand, and pull with your right. Sometimes you really

need to give the fiber a good tug -- it's easy

to be too tentative at first. What you are making

now is called a single.

When

you have two bobbins filled with single-ply yarn,

you can make a double-ply yarn by putting your bobbins

on something called a "Lazy

Kate" and attaching the ends to a leader

on a new bobbin. Plying makes a more balanced yarn,

particularly for beginners who have a tendency to

over-twist their singles [me included!]. When plying,

you treadle in the reverse direction -- usually counterclockwise.

As the two singles wrap together, you pull them forward

with your free hand [guiding with your left, pulling

with your right for a right-hander] and allow them

to wind on to the bobbin.

Niddy-noddy

time! When you've made a bobbinful of yarn, this

strange implement helps you turn it into familiar-looking

skeins. By wrapping the yarn from the bobbin onto

the niddy, you create a large loop in a small amount

of space, which is then tied in sections and removed

by sliding it off one "shoulder" of the

niddy.

Stop

and beam with pride. It's your first skein!

This

isn't Superwash from the yarn store. Before

knitting with your new yarn, you should wash

it. It can shrink anywhere from 10-25%, and

wouldn't that be a terrible surprise the first

time you washed whatever you make from it! I

stuck with shampoo, but "plain soap"

is also recommended [see the The

Alden Amos Big Book of Handspinning for

recipes and extensive details, but don't use

laundry detergent: too many chemicals and brighteners].

Here's the fun part. You've got a dripping skein

in your hand and don't feel like standing there

all day. Whack it against your shower wall,

or go outside [my aunt's birdfeeder got pummeled

the day I was there!]. Not only will you forcefully

remove some of the water, but Lucy says this

also helps set the twist. Hang to dry, and ball

as usual.

Something

I learned while making the Eddie sweater is

that your yarn's gauge will likely change as

you continue to spin. Before committing to a

project, try to make enough yarn to complete

it. I didn't follow this advice, but had excellent

beginner's luck. Despite overtwisted yarn that

made the top of my sweater start to slant on

a bias, it compensated as I continued to knit,

and the finished object is just perfect. Using

a top-down circular needle pattern helped, too

- in this case, Knitting

Pure & Simple #9724. Another method

is to alternate yarn from different skeins as

you go along. Something

I learned while making the Eddie sweater is

that your yarn's gauge will likely change as

you continue to spin. Before committing to a

project, try to make enough yarn to complete

it. I didn't follow this advice, but had excellent

beginner's luck. Despite overtwisted yarn that

made the top of my sweater start to slant on

a bias, it compensated as I continued to knit,

and the finished object is just perfect. Using

a top-down circular needle pattern helped, too

- in this case, Knitting

Pure & Simple #9724. Another method

is to alternate yarn from different skeins as

you go along.

Now

knit yourself something beautiful! For more

information, check out the open directory guide

to handspinning, SpinOff magazine from Interweave Press or my

knitting website. I plan to grow and process

a dye garden this summer — stay tuned for

more adventures!

|