Knit smarter, not

faster

A manifesto of

sorts by Jenna Wilson

I had been knitting for

several years before I realized that the measure

of one's skill as a knitter is not merely

a tally of technical milestones or finished

projects. Rather, it is a product of

technical proficiency and the ability to supply

context to a knitting project where little

context, or no context, is provided.

What do I mean? Well,

there are knitters who routinely knit sweaters

from written patterns as gifts for their extended

family every year, but cannot improvise a

garment on their own. Yet there are

also "novice" knitters who have

no hesitation in knitting an allegedly difficult

project, or combining disparate design elements

into one garment. There are knitters who seem

to be incapable of deviating from a written

pattern, and others who must always apply

their own improvements. And there are knitters

who are disappointed when they finally try

on a finished garment and discover the fit

isn't right, while other knitters are able

to spot potential fit issues before committing

the resources and time to a project, and either

work around or avoid the problems altogether.

What's the difference? Is

it a question of having the confidence to

make mistakes and rip back if necessary? Not

entirely, because ripping back is a fact of

knitting life. If the experience of

knitting from patterns can teach you anything,

it's that many patterns contain errors that

the technical editors miss, and that anyone

can misread even straightforward instructions. Is

it tunnel vision from knitting too many intarsia

reindeer? That's really a taste issue, and

beyond the scope of this article [not to mention

beyond hope].

This difference is best

described as the degree of context the knitter

is able to bring to his or her work.

Call it knitter's instinct, or plain common

sense; context is the ability to knit "smarter"

-- the ability to supply details to a pattern

with deficient instructions, or to identify

the source of errors and the means of correcting

them. It's having a starting point for creating

an original design, insight into shortcuts

for making knitting, fitting or finishing

easier, and being able to visualize the big

picture.

Context is also difficult

to teach. Ideally, it's gained by experience,

but that's not the case for everybody. And

while it's possible to teach the individual

morsels of knowledge that form part of knitting

context, it is not as easy to impart the insight

that combines all those elements into successful

garment design. Part of that insight

is an understanding of garment structure,

and how that structure can be achieved.

Most instructional knitting

books concentrate on only the technical aspects

of knitting: they are catalogs of cast-on

techniques, decreases, increases, and buttonholes.

But all such techniques are merely the building

blocks of a knitted garment.

What instructional books

are often missing is an appreciation of garment

design and structure. Without the ability

to shape knitted pieces into a properly fitted

garment, knitting merely produces a substrate

for texture or colour. That's fine if you're

planning to knit and wear pillowcases; but

if you wish to be able to knit garments that

fit your body, rather than merely sit in storage,

you need to knit smarter: you need to understanding

the shaping you wish to achieve, as well as

the techniques that allow you to achieve it.

Developing this knowledge

has additional benefits, even if you don't

have design aspirations. Being able to supply

your own context to patterns will make pattern

reading easier, and allow you to work around

errors, because you will understand the logic

behind the written instructions. It will also

help you think ahead in your knitting, and

plan changes to improve fit and make finishing

easier.

What I hope to do with this

column is to help you develop your own context

and knit smarter by focusing on structure

and form. So, here's the plan. The rest of

this article is preparatory work. We'll

review one element of knitting smarter: reading

your knitting pattern properly, and learning

how to extract information from whatever written

instructions you have -- a necessary step

on the way to effecting alterations and improvements. And

in the following two issues of Knitty, we

will concentrate on one aspect of the theory

behind garment design and structure, but with

a practical application: we'll learn to add

sleeves to a sleeveless garment, starting

first with the simple drop shoulder and modified

drop shoulder, then moving on to the set-in

sleeve with shaped cap.

Reading comprehension

One important method of

avoiding grief in knitting is mind-bogglingly

simple, but often ignored. If you read through

a pattern before you pick up the needles,

the actual process of knitting the pattern

will be easier. And if you're planning to

make improvements or changes to the design,

particularly fitting alterations, it's an

excellent idea to milk the written pattern

for as much information as possible.

Preparation

Start by taking a look at

what you've got. Hopefully, you have

complete -- if cryptic -- knitting instructions,

any necessary charts and symbol keys, separate

instructions for special stitch patterns,

and a schematic. At the very least, you should

have some instructions. Not every pattern

includes schematics, particularly those that

are short on space [if you collect "vintage"

knitting patterns and magazines, you will

have noticed that schematics were frequently

omitted].

Before committing to knit

this pattern, you also will have hopefully

determined that the garment style is actually

flattering to you [or the intended recipient].

First, read

the pattern from beginning to end. You're

not reading for correctness, just glaring

errors and clarity.

-

Is there sufficient

information to enable you to choose a

suitable yarn -- at the very least, the

intended gauge?

-

Based on the photos

and description, count the number of parts

you need to knit to yield a whole garment

[for example, for a cardigan there might

be a back, two sleeves, two fronts, a

front band and a neck band]. Are there

instructions for each of these parts,

or is something missing?

-

Wherever the pattern

uses some unfamiliar abbreviation, or

references a stitch pattern [for example,

"herringbone st" or "fancy

stitch patt"], check to make sure

a definition is provided.

-

If the pattern references

one or more charts, make sure they're

present, and check the symbol key to make

sure you understand each symbol. If

your pattern requires that you follow

more than one chart at a given time [for

example, if you are knitting an Aran sweater],

make working copies of these charts, and

tape them to a separate piece of paper

so they are side by side, if that will

help you. If you run through multiple

repeats of one chart while you're still

working the first repeat of another, consider

making multiple copies of the shorter

chart, and tape them in place, too.

-

If the pattern makes

use of recursive or otherwise cryptic

instructions, now is the time to decipher

them. Write them out in detail, while

your head is clear, for reference later.

-

If you notice any "at

same time" or similar instructions

that expect you to execute more than one

shaping step at a time [a tip on identifying

those problem areas is given below], highlight

them in the text. Otherwise, you

may miss them when knitting the pattern,

resulting in some inconvenient ripping

back.

Next, if your pattern has

a schematic and you have the means, make

an enlargement of the schematic

so that you can write numbers, measurements,

and brief notes on it comfortably -- aim to

fill most of a letter-sized piece of paper

with the schematic of a single piece. If

you don't have the means to make an enlargement,

sketch out your own supersize schematic on

a piece of graph paper, and write in any measurements

provided on the schematic. If your pattern

does not include a schematic, sketch out your

own, making your best guess from the photographs

and descriptions provided.

Make

a note of the pattern's gauge

per inch

at the top of your schematic. Gauge is typically

given as a number of stitches and rows over

a span of 4 inches [10 cm] or 2 inches [5

cm]. It's an easy calculation to break this

down as numbers of stitches and rows per inch

[2.5 cm], and it's handy to have these numbers

at your fingertips.

Visualization

|

For now, we'll stick

with a typical sweater pattern, which

is knit in pieces from bottom to top.

This particular hypothetical pattern

has a deep V-neck and set-in sleeves.

Take a look at your schematic, and apply

some geometric logic.

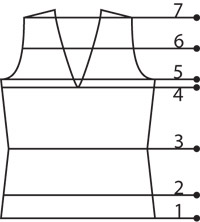

Looking at our hypothetical

design, we notice that there is some

ribbing at the hem, decreases and increases

defining the waist, as well as the expected

armhole decreases and neck shaping.

|

The hypothetical front

of a hypothetical sweater

|

|

In fact, we can draw

horizontal lines across the schematic

to denote the various shaping zones,

as shown on the left.

In this schematic,

the front starts with ribbing at line

1. The ribbing ends at line 2, at which

point there are decreases that taper

the body to line 3. After line 3, the

width increases up to line 5; however,

you'll note that first, at line 4, the

V-neck begins. Between lines 5

and 6, the armhole is decreased, and

then worked even up to line 7, which

is where the shoulder shaping begins.

|

Dividing

your schematic

into shaping zones. |

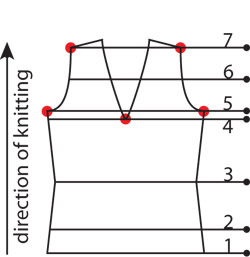

Now, imagine that you were

to hold a ruler or other straight edge across

the schematic, and slide the straight edge

upwards, in the direction of knitting.

Examine the orientation and number of lines

in the schematic that intersect the straight

edge at various positions.

|

| Sliding a

straight edge along the schematic. |

Because we're knitting upwards

from the bottom [the same would apply to knitting

downwards from the top], straight or "even"

knitting with no increases, decreases, or

other shaping is represented by schematic

lines that meet the straight edge at a right

angle [90Å]. An angle other than a right

angle suggests that there is some shaping

to be worked in that zone.

In the left-hand diagram,

two lines of the schematic do not meet the

ruler at a right angle; instead, they slant

towards the center of the schematic.

You can infer quite easily that there must

be some decreases worked in this area, and

you should be able to confirm this by checking

the written instructions. Furthermore, the

lines of the schematic are symmetric around

the imaginary center line of the garment;

they slant at the same rate towards the center,

and again, you can easily infer that the decrease

instructions for either side of the garment

must match.

In the center diagram, the

upper edge of the ruler now intersects four

lines, all of them at non-right angle intersections.

The fact that there are four lines obviously

means that there are two parts to the garment

to knit at that stage -- the left side and

the right side of the neck.

|

But there's something

else to note: on each side, the angle,

or slope, of the lines intersecting

the ruler are different. The slope

of the neckline is different from the

slope of the side edge at this point.

The fact that the slopes are different

suggests that you have different shaping

instructions for each edge that must

be followed [the notorious "at

same time" instructions].

Similarly, in the

right-hand diagram above, there are

two pieces [left and right shoulder]

to be knit, and the design lines have

different slopes: while you are shaping

the shoulders, you should be alert to

the fact that you may have some neck

shaping to work at the same time. You

may have already flagged these potential

problems during your first read through

the pattern; if not, you can go back

and highlight them now, and even highlight

the trouble zones on your schematic

[see diagram at left]. |

Highlighting

trouble ["at same time"] spots.

|

Calculation

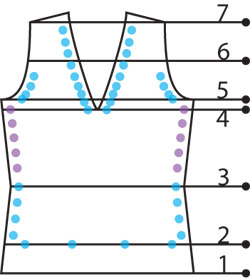

When preparing to knit a

pattern, it's also useful to write

in your own checkpoints --

stitch and row counts at the end of each shaping

zone in your pattern.

Many patterns provide stitch

counts at certain points: for example, after

all the decreases from the hip to the waist

of a pullover have been completed, or after

all the increases in a sleeve have been completed. However,

patterns do not always provide stitch counts

after the completion of each shaping zone

in a pattern, and fewer provide row counts. For

example, instructions often read "knit

until piece measures 14 inches from cast on

edge, ending with WS row," rather than

providing the exact number of rows to be knit. Since

a measurement of length in knitting before

blocking can be grossly inaccurate, it's wiser

to knit to a set number of rows rather than

holding a measuring tape to your knitting.

|

Based on the written

instructions in the pattern, make some

simple calculations now based on your

gauge, and write the stitch and row

count you expect to have at the end

of each zone on your schematic, as well

as the corresponding measurements in

inches or centimetres. At the same time,

count the number of decreases and increases

you expect to make in each zone, and

mark them on your schematic as well. |

| Marking increases

and decreases on the schematic. |

Immediately before

committing to the project

Swatch

with your chosen yarn.

Really.

There are knitters who proudly

claim that they have never swatched before

knitting a sweater in their lives. Have you

actually seen them wear those sweaters? And

do you want to look like them?

There are two circumstances

where it is reasonably safe to forego swatching:

when an exact finished size for a single knitted

piece is not crucial, and when you have used

that particular yarn with that particular

size of needles so frequently that you can

accurately predict the characteristics of

the knitted fabric they will produce. A

scarf or shawl is still functional even if

your knitting gauge is a little off, and you

probably can compensate for any extra or lost

width or length by working fewer or more repeats

of the pattern -- assuming you have sufficient

yarn. But when a knitted piece is meant

to be seamed to another or to conform to a

particular body shape and size, if you want

to be reasonably assured of the final result,

you will knit a six-inch [15 cm] square

swatch before you embark on the actual

project. And you will like it.

During knitting

As you knit, refer to your

schematic as well as the written pattern,

and check off

decreases and increases as

you knit them. By tracking the increases and

decreases, and by marking the points at which

there are "at same time" instructions

to be followed, you have a warning system

in place that will hopefully alert you to

follow the written instructions more carefully,

thus avoiding mistakes.

Some patterns will explicitly

tell you to work all your shaping stitches

one or two stitches in from the edge, so that

you are left with a clean selvedge for seaming. Other

patterns may miss that detail, and simply

instruct you to "dec 1 at each side." In

that case, make

a note of how you've decided to work increases

and decreases along garment edges. It

will save guesswork later when you come to

work matching pieces, such as the second sleeve.

Once you reach the dreaded

"at same time" or "work as

for other side, reversing shaping" shoulder

and neck shaping of a garment, if the instructions

are not explicitly provided, take the time

to record in

detail exactly how you are knitting the first

side -- on what rows you have

chosen to work decreases to shape the neckline,

for example. That way, you will be able to

work the mirror image on the other side of

the neck with more confidence.

But do I have to?

Carrying out each and every

one of these steps in preparation for a knitting

project does sound laborious. Of course, it

isn't necessary to do everything listed above.

However, if you anticipate difficulties in

interpreting the instructions on the fly,

or you are concerned that a pattern is beyond

your current skill level, it's a good idea

to read the pattern through before you start

so that you're not caught by surprise. And

if you are planning any modifications to the

pattern, whether to customize the fit or alter

the style, it's extremely useful to sketch

a large schematic and have all the relevant

numbers at your fingertips. In the upcoming

articles on sleeves, we will assume that this

type of preparation for the original sleeveless

pattern has already been done.

Resources

Gibson-Roberts, Priscilla,

and Deborah Robson, Knitting in the Old

Way: Designs and Techniques from Ethnic Sources

[Nomad Press, 2004]. This book was recently

republished. It's a wonderful reference, covering

the construction techniques, stitch patterns,

and shaping in many folk sweaters from around

the globe; and in fact a passage from this

book was the inspiration behind this series

of articles.

Newton, Deborah, Designing

Knitwear [Taunton, 1998]. This book is

an excellent reference for anyone who wants

to embark on handknitted garment design at

any level. In addition to covering the

basics of garment shaping, Newton encourages

exploration [via swatching] of knitted fabric,

texture, and colour, and demonstrates her

sources of inspiration for knitwear designs.

Walker, Barbara, Knitting

from the Top [Schoolhouse Press, 1996]. Nothing

focuses your mind on the shaping of a garment

like knitting it in a different direction.

Even if you do not choose to knit from the

top down, reading through this book with its

verbose directions will help you appreciate

garment construction and what knitted fabric

can do for you.

None of the above references

provide you with hard pattern instructions,

or if they do, those instructions are provided

as an afterthought. The directions in these

books are phrased as general directions, and

you are expected to work with your own numbers

[measurements, gauge, finished dimensions]

to arrive at a finished product.

"The Method of Three,"

INKnitters. This

is a three-part article on adjusting pre-written

patterns to fit; however, there's probably

enough data contained in the article to allow

you to calculate the instructions for a sweater

from scratch. So far, the first two

parts of this article have been published

in the winter 2003 [Issue #11] and spring

2004 [Issue #12] issues; the third should

be published in summer 2004 [Issue #13].

While you may not need the information in

these articles right away, I recommend that

you pick up copies of these issues while they're

still available.