|

|

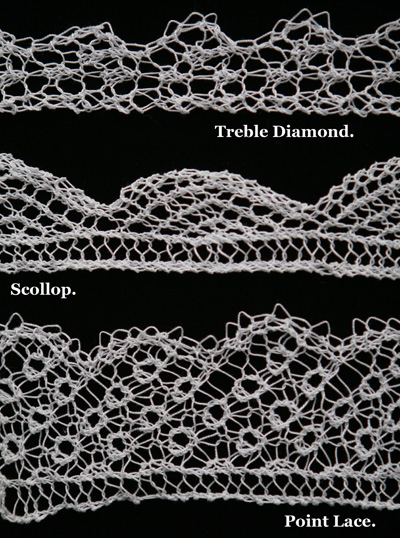

If your taste in design bends toward minimalism and you agree with that nice Mr. van der Rohe that “less is more,” you might want to look away. Because today we’re going to talk about embellishment. Although it has perfectly respectable roots in Old French and Latin expressions meaning “to make more handsome,” the word “embellishment” is an expletive in modern design circles. If something has been well designed, so the thinking goes, it does not require embellishment. Embellishment is a trick, a cheat, a smokescreen. Embellishment obscures form and hinders function. Embellishment is gilt on a plastic lily, lipstick on a lopsided pig, a rhinestone-studded fourth wheel on a tricycle. That’s what they say, anyhow. But I like it. I grew up admiring my mother’s and grandmother’s skill at taking the plain and making it fancy. It might be only a little touch, like decorative stitching around the collar of a home-sewn blouse. Or it might be what were, to my young eyes, the almost royally ornate Sunday best handkerchiefs my grandmother had saved in her lavender-scented top drawer. Cut from the backs of white men’s work shirts that had passed their prime, the generous squares of cotton were bleached to a fare-thee-well, hemmed by hand, embroidered with a tiny rosebud or a set of initials, and edged with homemade (usually crocheted) lace. Some might have thought them fussy, but for the women like my grandmother – who grew up poor but proud in a Pennsylvania coal patch – they were a rare bit of pure luxury, of beauty for beauty’s sake. Those women couldn’t afford to buy it, but they could create it for themselves. If you’re a typical twenty-first century knitter, chances are you can sympathize. The impulse to embellish pervades nineteenth-century knitting books. Not surprising, I suppose, considering that the Victorians were notoriously – some might say infamously – preoccupied with applied decoration. Mixed with the patterns for sensible socks and mitts are scores (if not hundreds) of curious stitch motifs, including enough lace edgings to connect New York and San Francisco with a thin white ribbon of faggoting, leaves, vines, scallops, peaks, and diamonds. Below you’ll find three superlative examples by the gloriously-named Mademoiselle Eléonore Riego de la Branchardière. Mademoiselle R. de B. was an early knitting and crochet rock star, with a string of wildly popular pattern books and a gold medal for crochet at the Great Exhibition of 1851. She was – or so her biographer claimed – the child of a displaced French nobleman and an Irish aristocrat; and there is certainly something in her laces that could be seen as the combination of French elegance with Irish imagination. They are also, once one has worked the bugs* out them, a hell of a lot of fun to knit. The question, I suppose, is what earthly use lace edgings are to a modern knitter. Not many of us carry handkerchiefs in the Kleenex era, on Sunday or any other day. And you may be a fancy collar sort of person; but then again, you may not. On the other hand, consider how many special occasion knits seem to be called for just when other demands of that special occasion (i.e., finding a caterer, sending invitations, talking to a therapist about your new in-laws) begin to cut into your knitting time. It may be that a lace edging, rather than a larger undertaking, will serve the purpose and save your sanity. A few possibilities for Mademoiselle’s patterns: Weddings. Instead of undertaking a shawl, consider a new lace edging for a vintage linen handkerchief; or knit up a lace garter. Rather than knitting an entire veil, trim a sewn veil with your own handiwork. Knitting for a wedding need not be epic to be beautiful and treasured. Births. Nothing shows off a newly-minted baby like hand-knitted lace. Attach manageable lengths to a simple store-bought ensemble for low-stress luxe; or collaborate with a relative or friend who knows his/her way around a sewing machine. Housewarmings. To celebrate a new home, or some other milestone event, give a table runner, a set of pillowcases, guest towels or napkins with lace trim. (And for heaven’s sake don’t worry that they might spend most of their time in a drawer. That’s what they’re supposed to do.) *One of the featured patterns was missing the entire middle row. Another ran off the rails just before the end of an otherwise successful journey. I admit that while undertaking repairs, I called Mademoiselle quite a number of unkind names in both French and English.

|

|

translated by Franklin Habit from Knitting, Crochet and Netting (1846) by Eléonore Riego de la Branchardière Scollop Treble Diamond Point Lace

|

|

FINISHED MEASUREMENTS |

| Will vary according to yarn and needles employed. Single repeats

of the models shown (knit with materials indicated below) measure

as follows: Scollop Lace: 2.25 inches long x 1.5 inches wide Treble Diamond Lace: 1 inch long x 1 inch wide Point Lace: 1.25 inches long x 2 inches wide |

|

MATERIALS |

|

GAUGE |

| 40 sts / 48 rows = 4” in stockinette stitch (unblocked, because let’s not kid ourselves) |

|

PATTERN NOTES |

| Yarnover at beginning of row: To work a yo

as the first stitch in a row, wrap the working yarn over the

needle from front to back, then work the next stitch as directed.

The little loops thus created along the outer edge of the piece

will look especially pretty if you take care to open them up

during blocking.

K3tog: Knitting 3 sts together is Mlle Branchardière’s standard double decrease. It’s also a gigantic pain in the kazoo when using fine cotton thread and/or less-than-sharp needles. If you choose to substitute another double decrease, I promise not to tell anybody. I find slipping the first st, knitting the next 2 sts together, then passing the slipped st over them to be quite satisfactory. |

|

DIRECTIONS |

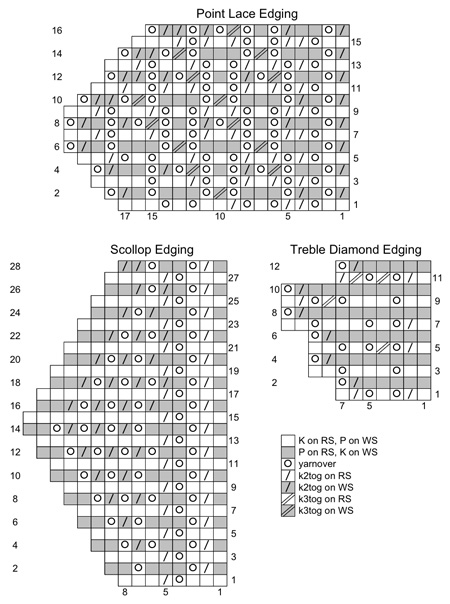

TREBLE

DIAMOND EDGING TREBLE

DIAMOND EDGINGCO 7 sts. Row 1 [RS]: K1, k2tog, yo, k1, yo, k2tog, k1. Even-Numbered Rows 2-12 [WS]: Yo, k2tog, k to end. Row 3 [RS]: K2, yo, k3, yo, k2. 9 sts. Row 5 [RS]: K1, k2tg, yo, k3tog, yo, k1, yo, k2. Row 7 [RS]: K1, k2tog, yo, k1, yo, k3, yo, k2. 11 sts. Row 9 [RS]: K2, yo, k3, yo, k3tog, yo, k2tog, k1. Row 11 [RS]: K1, k2tog, [yo, k3tog] twice, k2tog. 7 sts. Repeat Rows 1-12 until edging is desired length. See finishing directions below. SCOLLOP EDGING POINT LACE EDGING |

|

FINISHING |

| ABOUT THE DESIGNER |

Visit his blog at the-panopticon.blogspot.com. |

| Pattern & images © 2010. Franklin Habit. Contact Franklin |