How to Get Hooked: Information and instructions for knitters who want to learn how to crochet

INTRODUCTION

How to Get Hooked

by Julia Madill

As the new crochet columnist for Knitty, I want you to know I get it. This is KNIT-ty, not CROCHET-y! In this column, I aim to share some fun crochet tips and techniques, knowing I am primarily speaking to the unconverted: knitters. Fear not, my stick-wielding friends! I am one of you! As someone who learned to knit first, crochet second, I hope to guide you down the same path and, hopefully, remove some stumbling blocks along the way.

Reading Crochet Patterns for Knitters

Let’s start with a frequent frustration for knitters: the written crochet pattern. For those more comfortable wielding two sticks than one hook, the gobbledygook of crochet pattern text can make your eyes cross. So many words! So many weird abbreviations! What’s with all the turning?

One of the biggest differences between knitting patterns and crochet patterns is this:

- Knitting patterns need to tell you what stitch to make in the next stitch.

- Crochet patterns need to tell you what stitch to make and where to make it.

In general, when we knit, the order of our stitches is all laid out for us. We’re working with several “live” stitches in rows or rounds and the next stitch requires no explanation. The next stitch is simply the next stitch on the left-hand needle. The second stitch is the one after that, and the third stitch after that. While there are exceptions, for the most part, there isn’t any guesswork required to know which stitch is “next” and as a result, knitting pattern instructions don’t need to spell it out for us.

In knitting, the “next” stitch almost always refers to the first stitch on the left-hand needle.

Crochet on the other hand, has just one “live” stitch at any given time. Whether you work in rows or rounds, typically only one loop remains on the hook after completing a stitch. This means it is incredibly easy to work stitches in any kind of order imaginable. While the “next” stitch in crochet usually refers to the next unworked stitch of the previous row or round, that doesn’t necessarily mean that will be the next stitch you work into. This anything-goes order of stitch-making is one of the reasons crochet is so great for lacy stitches and sculptural, multi-directional projects. If you want to think of it in knitting terms, it’s as if all of your stitches but one are bound off and the next stitch could be picked up anywhere you like.

In crochet, where you work the “next” stitch is often the first stitch to the left of the stitch on the hook, but it is common for stitches to be skipped or placed into other areas of your work.

What’s more, crochet stitches don’t even have to be worked into other stitches. It’s very common in crochet patterns to work into a “space” which could be the open space under a chain or between two stitches. There are also multiple ways to work into a crochet stitch itself. You may be asked to work around the post of a stitch, into the back or front loop only or even into a third loop. All of these variations make for some really cool crochet effects, but they do require a lot more yackety-yack in a pattern to convey all this information.

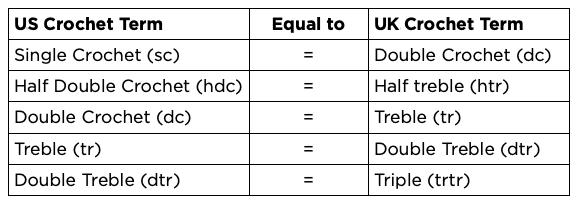

To add to the complexity, I find crochet pattern language varies more from source to source than it does in knitting. One BIG thing to note is that crochet has two popular terminologies: US terminology and UK terminology. What’s worse, these two systems use many of the same words, but with different meanings! Most modern patterns will indicate which terminology is used, but when in doubt, search for an exclusive term: “single crochet” is not used in UK terminology and “half treble” is not used in the US.

Now that we know some general differences between knit and crochet instructions, let’s look at a few variations in crochet pattern writing styles.

Traditional

Sources that compile patterns from multiple designers like magazines, larger yarn companies and many stitch dictionaries typically use a traditional pattern writing style.

With minor variations from source to source, what I am calling “traditional” crochet pattern language is what I see most often in patterns from the English-speaking western world. This style has been used for decades, and it looks something like this:

Ch 24 (28, 32).

First row (RS): 1 dc in 4th ch from hook (sk’d ch-3 counts as 1 dc), ch 1, sk next 3 ch, *3 dc in next ch, ch 1, sk next 3 ch; rep from * to last ch, 2 dc in last ch. Turn.

2nd row (WS): Ch 3 (counts as 1 dc throughout), [3 dc, ch 1] in each ch-1 sp to last ch-1 sp, 3 dc in last ch-1 sp, 1 dc in top of ch-3. Turn.

Other than obvious abbreviation differences, there is a lot of familiar territory here between this crochet writing style and your average knitting pattern.

What’s the same?

- Row number indications

- Right side/wrong side indications

- Multiple size number indications

- Actions separated by commons (or sometimes periods)

- Repeats indicated with asterisks, brackets or parenthesis

What’s different?

- Each stitch to be made is followed by an indication of where to make it

- There is special instruction at the beginning (or sometimes end) of the row for “turning chains”

- Rows are often finished with the instruction “Turn” to indicate turning the work to the opposite side before beginning the next row

- Rounds are often finished with instructions on how to join the last stitch to the first

Technique Specific

Crochet patterns that primarily use one stitch or technique are often written differently than the “traditional” style. Allies from Knitty’s Spring Summer 2025 issue (shown top left) uses the filet crochet technique which is often only explained with a chart.

Sometimes crochet patterns are blissfully brief, and this is usually because the project uses just one stitch pattern or technique throughout. In this case, after the technique is covered, only color changes, shaping or other modifications need to be explained in the text or often, a chart. In knitting terms, this type of pattern would be similar to an intarsia, stranded knitting, or mosaic pattern.

Of course, some techniques are exclusive to crochet and don’t have a direct equivalent in knitting. In the crochet world, amigurumi (stuffed toy) patterns are often designed using only single crochet stitches in the round. As a result, certain assumptions can be made which allow the designer to keep the pattern text brief.

Eg.

- MR, *sc* x 6 (6)

- *inc* x 6 (12)

- *sc, inc* x 6 (18)

- sc in each stitch around (18)

This is about as succinct as you can get for a crochet pattern. Virtually everything is abbreviated, and the instructions are distilled to their bare essentials. This only works because it is assumed the crocheter already knows:

- This pattern is worked in the round

- Each stitch is worked into the next stitch to the left

- What type of “inc” (increase) to make

- How to treat the beginning of the round (ie; whether there is a beginning chain or not)

- How to treat the end of the round (ie; whether you join the round with a sl st or not)

- That the instructions between asterisks *-* are to be repeated by the number after x

- The number in brackets at the end of each row is the stitch count

That’s a LOT of assumptions. That said, this format is a perfectly acceptable way to write a crochet pattern if the assumptions are clearly explained somewhere else.

Crochet designs that rely on charts may also have very little text. Mosaic crochet, tapestry crochet, and filet crochet are all techniques that, once the basics are covered, can be communicated much more easily with a chart than text instructions.

So, how does this writing style compare to knitting patterns?

What’s the same?

- Mosaic and intarsia crochet charts are often read exactly the same way in both knitting and crochet and the same chart can be used for both skills

What’s different?

- The techniques are often exclusive to crochet and therefore, use different shortcuts than a knitting pattern would to keep text brief

Diagrams

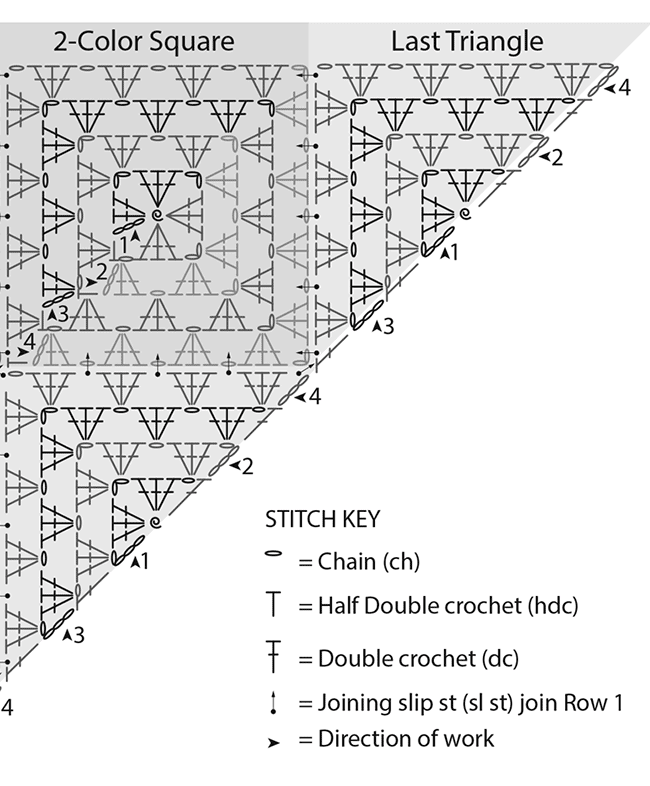

The Shadowboxer Shawl I designed for Knitty’s Deep Fall 2024 issue has full-text instructions (traditional style) as well as stitch diagrams.

Because crochet stitches vary in height and placement, they won’t fit on a square or rectangular grid the same way knit stitches do. Perhaps this is why crochet charts are often called “diagrams” instead of charts. Crochet stitch symbols vary in size, shape and orientation to better represent how the stitches look in reality.

A section of the chart for Shadowboxer.

For visual learners, these diagrams can be a godsend. That said, if you are looking to read crochet pattern charts with your knitting hat on, you’ll want to note a few key things:

What’s the same:

- The chart represents what the work looks like from the right side

- Rows and rounds are numbered

- Each stitch is represented by its own unique symbol

- The chart will be accompanied by a key explaining the symbols

- Symbols vary from source-to-source, but the basics are fairly standardized

What’s different

- Most crochet charts do not have gridlines to delineate rows or rounds

- Crochet charts may be read in almost any direction (not just left-to-right or right-to-left)

- Crochet stitch symbols are not always oriented in the same direction

Once you become familiar with the basic stitch symbols, crochet diagrams are a cinch to follow. Some of the best crochet patterns will have both text and a chart which means you can cross-reference any points of confusion.

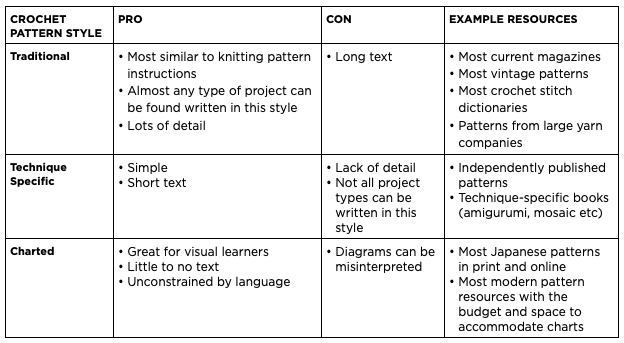

I find knowing why a pattern is written a certain way is helpful. These broad categories don’t cover every pattern style, but the good ones won’t unnecessarily re-invent the wheel. Which style appeals to you will take some experimentation. Here’s how I think they stack up:

As a knitter, you have an advantage over other new crochet pattern readers. The materials list, gauge, sizing and many other basic pattern elements are exactly the same in both knit and crochet. Just remember, the rest is not knitting. That may be obvious, but knitting expertise may actually get in the way of understanding crochet. Try not to make assumptions or fill in the blanks with your knit-knowledge and read your crochet patterns carefully. Knowing how to both knit and crochet opens up a world of yarny possibilities so don’t let the pattern language hold you back. You’re smart. You’re a knitter. You can do this!

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Julia Madill is a knit and crochet pattern designer, tech editor, and graphic artist, and Knitty's new Crochet Editor. She loves sharing what she has learned in her 10+ years of experience in the yarn industry, providing others with the tools to create in their own style, voice and aesthetic. Her book, Every Way with Granny Crochet is available from David and Charles publishers.

Julia Madill is a knit and crochet pattern designer, tech editor, and graphic artist, and Knitty's new Crochet Editor. She loves sharing what she has learned in her 10+ years of experience in the yarn industry, providing others with the tools to create in their own style, voice and aesthetic. Her book, Every Way with Granny Crochet is available from David and Charles publishers.

She lives in Toronto with her partner, two daughters, a cat named Pickles and a whole lot of yarn.

Text & images © 2025 Julia Madill